Iraj Pezeshkzad and His Hafez: A Note on Hafez in Love

Iraj Pezeshkzad and His Hafez: A Note on Hafez in Love

Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi

Instructional Professor of Persian, University of Chicago

Patricia J. Higgins

University Distinguished Service Professor Emerita, SUNY Plattsburgh

Iraj Pezeshkzad is well known as a writer not only in Iran but also in the West, largely because of his satirical novel, Da’i Jan Napelon (Dear Uncle Napoleon).[1] That novel, which features the antics of members of a pseudo-aristocratic family in Iran of the 1940s, pokes fun at many widespread Iranian beliefs and behavioral characteristics.[2] It became a bestseller and the basis for a wildly popular television series which aired in Iran in the late 1970s. Reportedly, the streets of Tehran would become eerily quiet whenever a new episode first aired.[3] While both the book and the TV series were banned for a time in the Islamic Republic of Iran, bootleg copies were still widely circulated.[4] The book itself has been translated into more than a dozen languages. The English version translated by Dick Davis and entitled My Uncle Napoleon was first published by a small press devoted to Iran-related topics.[5] My Uncle Napoleon won the Lois Roth Prize for Literary Translation from Persian in 2001, and in 2006 it was issued in a second edition by a major trade publisher[6] with an introduction by the well-known writer Azar Nafisi[7] and an afterword by the author himself.[8]

Da’i Jan Napelon is indeed a classic of twentieth-century Persian literature, but it is by no means the only thing that Iraj Pezeshkzad wrote. According to one obituary, “he wrote more than 17 satirical novels and more than a dozen scholarly books and essays on history and literature.”[9] While at least one of these essays has been translated into English,[10] none of Pezeshkzad’s other novels had been until we undertook to translate Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand (Hafez, heedless of advice),[11] now available as Hafez in Love.[12] We started this project in 2016 after reading several of Pezeshkzad’s other novels and particularly enjoying every sentence and every word of Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand.

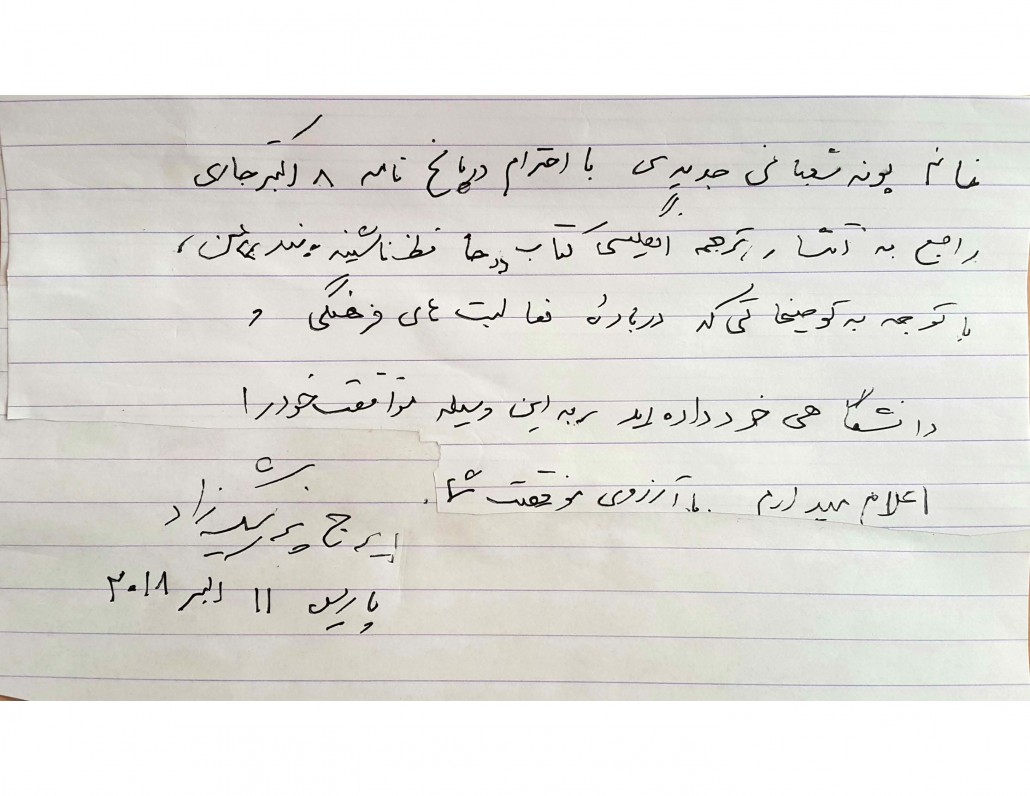

It was in October 2018 that we first contacted Mr. Pezeshkzad to ask for his permission to publish our translation. We made this contact through his son, who was introduced to us by Professor Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi of the University of Toronto and by Sorour Kasmai, who is the French translator of Pezeskzad’s Da’i Jan Napelon, Mon Oncle Napoleon.[13] We received a reply from Bahman, Mr. Pezeskzad’s son, the same day, saying that we had his father’s permission to publish the translation if Dr. Tavakoli-Targhi had given his blessing to our project. The same day, we called and spoke to Mr. Pezeshkzad as well. His voice was deep and kind, and after an explanation of our project and our qualifications, he told us that he would give us written permission to publish our translation, which we expected any publisher to want. At the age of 91, he had steady calligraphic handwriting (see Appendix); the date of the permission is October 11, 2018, and the place is Paris.

The next time we spoke with Mr. Pezeshkzad was in 2021 when we wanted to send him his complementary copies of our translation. He was as gracious and kind as he had been the first time that we spoke to him. He asked us to send him any reviews written on the book in English, which of course we agreed to do.

Later, we had the pleasure of inviting Mr. Pezeshkzad to talk about his works, including Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand, in the Heshmat Moayyad Lecture Series organized by the University of Chicago’s Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Department. After Professor Franklin Lewis introduced Mr. Pezeshkzad and listed several of his books, Mr. Pezeshkzad began his talk.[14] This was October 2021, and it was the last talk that Mr. Pezeshkzad gave before his death in Los Angeles on January 12, 2022, a few days shy of his 96th birthday.

Like most of Pezeshkzad’s other works, Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is at least in part a satire, and like several of his other works, it is a historical novel. Though Mr. Pezeshkzad told us he considered it more a historical novel than satire, the reader cannot help but notice the parallels between fourteenth-century Fars Province and Iran in the era of the Islamic Republic. Based on our experience, satire is one of the most difficult genres to translate because it contains cultural references and allusions that are sometimes impossible to recreate in the target language. Mr. Pezeshkzad’s satire is very subtle and clever, which makes the job of the translator even harder.[15]

Based on historical accounts, Pezeshkzad imagines a certain period in the life of Mohammad Shams al-Din Shirazi, arguably the best known and best loved Persian-language poet, better known by his pen name, Hafez. The time is 1354 CE and the beginning of Amir Mobarez al-Din Mozaffar’s rule over Fars and neighboring provinces. It is a time of political and social instability, which is arguably very similar to the situation of twenty-first century Iran. Just as in present-day Iran, in the novel the morality police are stripping the people of their freedom of speech and squelching the expression of any belief that goes against those of the ruling group. Similar, too, is the ostentatious religiosity of the ruling group and the expectation that those who aspire to power or favor will follow suit. Whether consciously or subconsciously, Pezeshkzad paints a vivid image of contemporary Iran in his depiction of the sociopolitical atmosphere in fourteenth-century Fars, the references of which are discernable by any Persian reader.

A reviewer of Hafez in Love suggests that the book can also be read as a commentary on the sociopolitical situation in the US in 2020 (although surely Pezeshkzad, writing in the early twenty-first century, did not intend that). This unnamed reviewer writes sarcastically,

Of course a ruler who favours executions, encourages mob violence, is anti intellectual and does not read, who has a nasty violent streak, who is not prepared to compromise but is full of his own self-righteousness, who does not know when his time is up, who appoints people to high positions purely on the basis of their loyalty rather than their competence and fires them at will and who pretends to be religious, while living a debauched life, is surely not something we could find in this era.[16]

That a novel set in fourteenth-century Iran written early in the twenty-first century speaks in this way to contemporary English-speaking readers is a testament to Pezeshkzad’s skill as a writer and to Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand’s candidacy for inclusion in world literature.

What makes the book especially interesting, yet challenging to translate, is the insertion of a number of poems, most by Hafez himself, some by his contemporary, ‘Obayd Zakani, as well as his predecessor, Sa‘di Shirazi, and others. The poems are so interwoven into the text that one wonders which came first in the writing process—whether it was the poems that inspired the author to write certain scenes, or whether the poems were selected and inserted after the framing of the story and the writing of the text.

For example, the narrator cites the following couplet several times as an example of Hafez’s carelessness in criticizing Amir Mobarez:

محتسب شیخ شد و فسق خود از یاد ببرد

قصه ماست که در هر سر بازار بماند

The morality officer became a pious sheikh and forgot his debauchery

It is my story that remained throughout the bazaar.

As another example, when welcoming a female guest, the character ‘Obayd Zakani cites a couplet from Sa‘di:

کس درنیامدست بدین خوبی از دری

دیگر نیاورد چو تو فرزند مادری

No one this exquisite has ever come in through a door

Nor has a mother ever brought forth a child like you.

Twenty-seven of Hafez’s poems are included in their entirety and similarly woven into the story. For example, the poem that begins with the following couplet is said by the narrator to have been written during the months that Hafez was mourning the death of his young wife:

آن یار کزو خانه ما جای پری بود

سرتا قدمش چون پری از عیب بری بود

The beloved for whose sake our house was a fairyland

Head to toe, like a fairy, she was flawless.

Whichever may have come first in the writing process, the poem or the narrative, the book as a whole shows Pezeshkzad’s mastery as a writer, his breath of knowledge of Iranian history and literature, and his command of Persian classical poetry. That the book has reached its thirteenth edition in Persian indicates the success of the novel and the talent of its author, Iraj Pezeshkzad.

Susan Bassnett, translation theorist and scholar of comparative literature, argues that novels based on classic books are translations of a sort because they are a kind of interpretation of the classic texts, and they wouldn’t have existed if those classic works hadn’t existed already. “It is a matter of using the past,” she says, “to make sense of the present.”[17] Translation is bringing back to life a work written decades, centuries, and millennia ago. It can be argued that Pezeshkzad’s Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is a translation of Hafez’s Divan and Pezeshkzad’s way of making sense of the present with the aid of Hafez’s poetry.

Most of the characters in Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand are real historical personages, and the large-scale events are historically accurate. Historians know very little of Hafez’s life, however, so the day-to-day events and the relationships between the characters in this book are largely the product of Pezeshkzad’s imagination as based on his reading of Hafez’s poetry. When asked why he depicted Hafez in this book as a playful young man, Pezeshkzad said he was sorry and disappointed that Hafez, this poet of love and joy, is always shown as an old man feebly holding a cup of wine with a beautiful young girl standing beside him. He said he did not at all picture Hafez this way when he was reading his poems; therefore, he wanted to make the readers see Hafez the way he sees him reflected in his poetry. In addition, he said he didn’t believe that Hafez was inclined toward Sufism, nor that he was a Sufi, but rather that he used Sufi and mystic expressions in his poems as a literary device.

Although Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is a novel rather than a history book, Pezeshkzad relied upon several historical sources which he acknowledged at the end of the book. They include: 1) Tārīkh-i ‘aṣr-i Ḥāfiẓ dar qarn-i hashtom (History of the age of Hafez in the fourteenth century) by Qasem Ghani, 2) Nuzhat al-qulūb (Purity of hearts) by Hamdollah Mostafa Qazvini, edited by Seyyed Mohammad Dabir-Siyaqi, 3) Dīvān-i Ḥāfiẓ (Collected poems of Hafez), edited by Parviz Natel Khanlari (text and notes), 4) Kullyāt-i Sa’dī (Collected works of Sa‘di), compiled by Mohammad Ali Foroughi, and 5) Kullyāt-i ‘Ubayad Zākānī (Collected works of ‘Obayd Zakani), compiled by Parviz Atabaki. Nevertheless, there have been certain criticisms about the veracity of the historical facts in the Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand.[18] For example, the existence of someone by the name of Golandam (the narrator of the book, purported to be Hafez’s best friend and brother-in-law) is contested, as is the date of Hafez’s birth, and therefore the age of Hafez in 1354. Moreover, some of the historical personages who appear as characters in the book may not have actually been in Shiraz that year. One must remember, however, that this is fiction based on history and not history itself, so the writer can employ his imagination in developing scenes and relationships.

The Hafez depicted Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is 23 years old, recently widowed, and still mourning the loss of his young wife, a cousin with whom he had been in love since childhood. His best friend and the first-person narrator of the story is Mohammad Golandam, who in reality is believed by some to be the author of the introduction to an early collection of Hafez’s poems—an introduction that provides most of what little we do know of Hafez, apart from his poetry. In the story, Golandam is married to Hafez’s sister who, along with her mother, is visiting relatives out of town for the entire several months of the story. While Hafez and Golandam spend their time with a bevy of male friends, some their contemporaries and some much older, the only female characters in the book are Bibi Khavar, an elderly woman caring for Hafez’s household in his mother’s absence; Jahan Malek Khatun, in real life and the story, a princess and poet; and Banafsheh, ‘Obayd Zakani’s housekeeper and servant.

Though Hafez is young in this story, his poetry is already presumed to be well known and widely admired not only in Shiraz but in far-off lands as well. For example, the narrator Golandam refers to “news from Anatolia, India, and Baghdad about the fame of Shams al-Din’s poems,”[19] and Pezeshkzad incorporates into the story the often-translated couplet,

به شعر حافظ شیراز می رقصند و می نازند

سیه چشمان کشمیری و ترکان سمرقندی

To the poetry of Hafez of Shiraz, they sing and dance,

The black-eyed beauties of Kashmir and the fair-faced Turks of Samarqand[20]

Pezeshkzad’s Hafez is a scholar as well as a poet, serving as secretary of the court archives under the previous ruler and doing research on such diverse subjects as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[21]

Despite such serious pursuits, Pezeshkzad’s Hafez is indeed joyful, and, for the most part, he takes great pleasure in life. He enjoys the company of his friends, appreciates the renown he has already received as a poet, and waxes eloquently over the natural beauty of Shiraz and its environs. He is rather intolerant, however, of hypocrisy, including what he sees as the hypocrisy of the new ruler, Amir Mobarez, and his followers. He makes his criticism of this group public through some of his poems and through his reluctance to join the ranks of the court poets. With his generally optimistic outlook, he refuses to see the danger that he has put himself in, and he ignores the advice of his friends to curb his tongue and make himself scarce for a time. (Hence the original title of the book, which can be translated as “Hafez, heedless of advice.”)

This Hafez is also playful, at times to a fault. He and the elder ‘Obayd Zakani (a writer of prose and poetry, often satirical and ribald, in real life as well as in the story) amuse themselves and others by baiting and then mercilessly making fun of fellow guests at literary gatherings. Further, he plays practical jokes, sending acquaintances on wild goose chases and then laughing boisterously that they took him seriously and fell into his trap. This joking at the expense of others gets Pezeshkzad’s Hafez into trouble, too, as he loses the support of some important allies at whom he has poked fun.

Other problematic characteristics of the Hafez portrayed in Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand are his manipulativeness and his sometimes-wanton disregard for the welfare of others. Early on in the story he pesters and needles Golandam until the latter agrees to accompany him to a party that Golandam thinks they both should avoid. Later on, he convinces Golandam, against the latter’s better judgement, to accompany him in the dead of night to check out the home of an acquaintance to see if the owner has returned from a journey. This escapade exposes him to arrest. While in jail, he prevails upon an admittedly quite willing admirer to smuggle out a letter for him, resulting in the man’s beating when he is caught with the letter while leaving the jail.

On the other hand, this Hafez does sometimes show concern for others, as when he expresses some regret at tricking a friend into preparing a long poem to recite in the presence of Amir Mobarez, who has no patience for long poems. “Then I became sorry,” he says, “that I had teased the poor guy. They say that if Amir Mobarez hears a long poem not only does he not listen, he also beats the poet.”[22] As another example, he decides to leave the home of an acquaintance who has given him shelter when he realizes the danger his presence poses for his host. “Whatever disaster might befall me,” he says, “it is better than that I cause trouble for the innocent Mehraban Ardashir.”[23]

In this book, Hafez’s lyric poetry is presented as addressing human beings and their strengths and weaknesses. In accordance with Pezeshkzad’s stated belief that Hafez was not a Sufi, the beloved in his poems is interpreted in this story as human rather than divine. While many scholars believe that the beloved of most classical Persian poetry, when human rather than divine, is a boy or teenage youth, in this story Hafez’s romantic interest is solely in females. For this reason, we translated the genderless Persian third-person singular pronoun as “she” rather than “he.”

When reading Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand, one can imagine the young Pezeshkzad in the character of playful Hafez and the elder Pezeshkzad in the character of respectable, meticulous, and funny ‘Obayd. Hafez’s infatuation with Jahan Malak Khatun also has some resemblance to the first love of Pezeshkzad, with the object of which he was never united, yet who he mentions when people ask him how he came to write Da’i Jan Napelon.[24] In Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand, Golandam describes Hafez’s playfulness and sense of humor as what saves Hafez in a period full of atrocities and ugliness—“a safety line that does not allow [him] [. . .] to drown of harshness in a sea of grief.”[25] Perhaps Pezeshkzad’s sense of humor was his savior too, enabling him to bear the sociopolitical problems that he faced which led him to seek exile in France. By his own account, he sorely missed Iran and longed to return to the country, but never felt that he could.[26] Yet he turned the pain of exile into at least one humorous essay[27] and at least one novel.[28]

For a comparison of Pezeshkzad’s Hafez with Hafez as interpreted by other scholars, we invite English-speaking readers to refer to Dominic Brookshaw’s Hafiz and His Contemporaries: Poetry, Performance, and Patronage in Fourteenth Century Iran,[29] as well as some of the English translations of selections from Hafez’s poetry, including Faces of Love: Hafez and Other Poets of Shiraz by Dick Davis,[30] Hafez: Translations and Interpretations of the Ghazals by Geoffrey Squires,[31] Wine and Prayer: Eighty Ghazals from the Divan of Hafiz by Elizabeth A. Gray and Iraj Anvar,[32] and The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez by Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn.[33]

When we spoke with the author in 2018 to get his permission to publish our translation, he told us that he would like us to use the same cover image as on the Persian version, which is a painting by Abbas Moayeri (1939-2020). He urged us to use the original painting so that the black stripe that runs across the cover of the Persian version would not appear. He further told us that the reason for the black stripe is to cover the breasts of the girl in the picture. Many of Pezeshkzad’s books criticize censorship, lies, and hypocrisy, as does Hafez in his poetry. It seems appropriate, therefore, that he wanted to break free from the censorship imposed on the original cover image. We tried reaching the artist then, but unfortunately, we only heard back from him two years later when the cover image was already chosen and approved. Soon after, Abbas Moayeri passed away, in October 2020.

Pezeshkzad’s art is in bringing the heavenly Hafez onto earth for readers to meet and to experience vicariously the occasions for which some of his poems could have been written.[34] The writer does not try to interpret Hafez’s poems directly. Instead, he masterfully employs the poems to create a hypothetical situation which could have inspired Hafez to compose a certain poem. He explains the existence of alternate versions of some of Hafez’s poems by the poet’s presumed penchant for repeatedly revising (ornamenting and embellishing, he would say) his works and even creates a story to illustrate the fictional Hafez’s attitude about the circulation of various versions. This story is related by ‘Obayd to Golandam,

One day at a gathering I heard a minstrel sing this couplet of his [Hafez]:

راهی است راه عشق که هیچش کناره نیست

آنجا جز آنکه جان بسپارند چاره نیست

The road of love is an endless road.

There is no choice there other than yielding your soul.

Several days later at a different place the minstrel sang the first line of the couplet this way: The sea of love is an endless sea. When I asked Shams al-Din why he wouldn’t say which version was his, do you know what answer he gave? With a laugh he said, “It’s fine if it is both, because there’s no difference. And for laughs, it’s not bad.” When I asked, “What laughs?” he said, “The same way that for several years now there has been arguing, quarreling, and strife between two groups of Sufis about a single phrase uttered by a Sufi master, if by chance my poetry, like the poetry of Sheikh Sa‘di, endures, then a hundred years, two hundred years, three hundred years from now, a difference of opinion will be found among literary scholars. One will say sea of love is correct and road of love is an error, and the other will say road of love is correct and sea of love is an error, and they will take the life of one another over road and sea. The youth of that time will laugh over their fights, and my spirit will take pleasure from their laughter.”[35]

In the talk that Pezeshkzad gave virtually at the University of Chicago three months before his death, he started by joking about his age. He then gave us a synopsis of his biography and discussed what led him to be a writer rather than the physician that his father wanted him to be and rather than a lawyer, for which he had studied in France. He said that he began his writing career by translating stories from French into Persian and publishing them Iṭṭilāʻāt-i haftigī (Weekly Iṭṭilāʻāt). He admitted that it was in France that he was introduced to literary social satire as it was a very common genre in French in those years after the end of World War II. He added that in order to help him earn a living while working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he wrote literary satire pieces and published them in the journal Ferdowsi for four years—essays which were then collated into a book.

He also talked about several of his books and what led him to write them. At a certain period in his life, he was sent from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on a mission to Algeria, and since he had a lot of time on his hands, sitting idly in the embassy, he started writingAdab-i mard bih zi dawlat-i ūst taḥrīr shud (One’s manners outdo one’s wealth),[36] which he said is his own favorite among the books he has authored. He stated that this book was very well received in the theatrical scene of Iran, and it was transformed into a play by the prominent actor and director, Davoud Rashidi (1933-2016). Yet, it did not go on stage because of an unfortunate incident that happened to the main actress. He added that, after the revolution, they tried to bring it to the stage, but this was stopped by the Revolutionary Guards and the play was subsequently banned. Later, he mentioned that the first play he translated from French to Persian was Voltaire’s Nanine. It seems that Pezeshkzad had an ongoing interest in theater and playwrighting. This is likely the origin of one of the distinctive features of his writing: his mastery of dialogue, which he employs in his novels, short stories, plays, and any writing he has embarked upon during his productive life.

The style of the Persian in Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is rather formal and literary. Perhaps having just finished writing another of his books, Ṭanz-i fākhir-i Sa’dī (The elegant satire of Sa‘di),[37] the author was influenced by Sa‘di’s language. Other than the few encounters with the cat, the rest of the text of Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand is written in a high register. Since the entire book is purported to be a manuscript written by Hafez’s close friend, this style helps the reader imagine the story being written in the fourteenth century. When we were translating this book, we tried to maintain this style to some extent. For example, we chose to use archaic or old-fashioned words in places where they seemed appropriate, such as “wenching,” “realm,” “tavern,” “mount” rather than “horse,” “goblet,” and “minstrel.” We also kept the sometimes quite elaborate expressions of politeness. For example, when the poet and princess Jahan Khatun enters the room, she is greeted by her fellow guests with several couplets of poetry. She responds in part by incorporating one of the poetic phrases: “[. . .] it is the presence of you dear poets that opens the door of blessing onto me.”[38] Because of this style, the English reader might find the text a bit stilted, pretentious, and verbose in places, but this is exactly how Pezeshkzad chose to write his historical novel. It is also how historic documents written in English sometimes sound to contemporary readers. Nevertheless, due to the existence of jokes here and there and the satirical nature of the book, it is not at all cumbersome to read.

Hafez in Love: A Novel, the English translation of Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand, won the 2021 Lois Roth Prize for Literary Translation from Persian, and it has been mentioned positively on several literary platforms. For instance, The Modern Novel website writes, “Pezeshkzad beautifully mixes in the various plot lines, so that we are always left wondering what will happen, while, at the same time, letting us enjoy the interchange between him and his friends, and the poetry of Hafez and his friends so that the book really is a joy to read.”[39] In his review of the book, Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab comments, “Hafez in Love is an extraordinary English rendering showing why this Persian poet of wine, love, and honesty has been the most widely read author from the Balkan to the Bay of Bengal for seven hundred years in the Islamic world. [. . .] A fantastic read to be recommended to everyone who loves Persia, Persian poetry, and historical novels.”[40] M. A. Orthofer writes about the novel and its translation in Complete Review: “Hafez in Love is a quite charming little historical romance, in a world that has become very unstable but where poetry also still matters. It’s an enjoyable read—and fans of Hafez and his poetry will certainly appreciate it, not least for how the poetry is cleverly employed in the novel.”[41]

As noted above, to date, the only books of Pezeshkzad that have been translated into English are My Uncle Napoleon and Hafez in Love. Yet, Pezeshkzad has written many more books that are waiting to be introduced to English-speaking readers, and we hope to see more of his books translated into English in the near future.

Appendix

Iraj Pezeshkzad’s handwritten note granting permission to the translators:

Translation of Iraj Pezeshkzad’s written permission to publish the English translation of his book:

Dear Ms. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi,

Respectfully, in response to your letter dated October 8, 2018, regarding the publication of the English translation of my Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand, considering the information that you gave me about your scholarly and academic achievements, hereby, I express my consent.

Wishing you success,

Iraj Pezeshkzad

Paris

October 11, 2018

Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi is instructional professor of Persian in the Department of Near Eastern Language and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. Some of her publications include The Art of Teaching Persian Literature: From Theory to Practice (Brill, forthcoming), The Bewildered Cameleer: A Novel of Modern Iran (Mazda 2023), The Routledge Handbook of Persian Literary Translation (2022), Island of Bewilderment: A novel of Modern Iran (Syracuse University Press 2022), The Eight Books: A Complete English Translation (Brill 2021), Hafez in Love (Syracuse University Press 2021), The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pedagogy of Persian (2020), The Oxford Handbook of Persian Linguistics (2018), The Thousand Families: Commentary on Leading Political Figures of Nineteenth Century Iran (Peter Lang 2018), Processing Compound Verbs in Persian (Leiden and University of Chicago Press 2014), and Translation Metacognitive Strategies (VDM Verlag 2009).

Patricia J. Higgins is university distinguished service professor emerita at SUNY Plattsburgh. As an anthropologist of Iran, she has published her work in Iranian Studies, Human Organization, Journal of Research and Development in Education, and NWSA Journal and as chapters in edited volumes. Some of her publications include Island of Bewilderment (Syracuse University Press 2022), Hafez in Love (Syracuse University Press, 2021), and The Thousand Families: Commentary on Leading Political Figures of Nineteenth Century Iran (Peter Lang 2018). In addition, she is co-editor of Classics of Practicing Anthropology: 1978–1998 (Society for Applied Anthropology 2000). At SUNY Plattsburgh, she served as a faculty member, an associate vice president, and then interim provost and vice president for academic affairs.

[1] Iraj Pezeshkzad, Da‘i Jan Napelon (Dear Uncle Napoleon) (Tehran: Farhang-e M‘aser Publishing House, 1973).

[2] For relevant examples, see M. R. Ghanoonparvar and Homa Katouzian in this issue.

[3] Emily Langer, “Iraj Pezeshkzad, celebrated Iranian satirist and author of ‘My Uncle Napoleon,’ dies,” The Washington Post, January 18, 2022.

[4] Langer, “Iraj Pezeshkzad.”

[5] Dick Davis, trans., My Uncle Napoleon (Washington, D.C.: Mage Publishers, 1996, 2000).

[6] Dick Davis, trans., My Uncle Napoleon (New York: Random House, 2006).

[7] Azar Nafisi, “Introduction,” in My Uncle Napoleon, trans. Dick Davis (New York: Random House, 2006), vii-xv.

[8] Iraj Pezeshkzad, “Afterword,” in My Uncle Napoleon, trans. Dick Davis (New York: Random House, 2006), 501-503.

[9] Farnaz Fassihi, “Iraj Pezeshkzad, Author of a Classic Iranian Novel, Dies at 94,” The New York Times, February 23, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/23/world/middleeast/iraj-pezeshkzad-dead.htm.

[10] Iraj Pezeshkzad, “Delayed Consequences of the Revolution,” in Strange Times, My Dear: The PEN Anthology of Contemporary Iranian Literature, eds. Nahid Mozaffar and Ahmad Karimi-Haddad (New York: Arcade Publishers, 2005), 105-14.

[11] Iraj Pezeshkzad, Ḥāfiẓ-i nāshanīdah pand [Hafez, heedless of advice] (Tehran: Nashr-e Qatreh Publishers, 2004).

[12] Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi and Patricia J. Higgins, trans., Hafez in Love: A Novel (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2021).

[13] Sorour Kasmai, trans., Mon Oncle Napoleon (Arles: Actes Sud, 2011).

[14] Iraj Pezeshkzad, “A Conversation with Iraj Pezeshkzad” (Heshmat Moayyad Lecture Series, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, October 28, 2021), https://nelc.uchicago.edu/heshmat-moayyad-lecture-series.

[15] For similar discussions, see Dick Davis in this issue.

[16] “Iraj Pezeshkzad: Hafez-e nashenideh pand (Hafez in Love),” The Modern Novel, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.themodernnovel.org/asia/other-asia/iran/iraj-pezeshkzad/hafez-in-love/.

[17] Susan Basnett, “Living in Translation,” keynote lecture presented at Bristol Translates lecture series, Bristol University, Bristol, England, July 5, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ih6wBl-n9qw, accessed September 3, 2022.

[18] Ahmad Madani, “A Critical Look at Hafez-e Nashenide Pand (Hafez, heedless of advice) by Iraj Pezeshkzad,” Artistic-Analytical Journal, Café Catharsis, https://cafecatharsis.ir/20127/نگاهی-انتقادی-به-رمان-حافظ-ناشنیده-پند/, accessed September 3, 2022.

[19] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, Hafez in Love, 156.

[20] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, 182.

[21] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, 13-14.

[22] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, 148.

[23] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, 82.

[24] Pezeshkzad, “Afterword,” 501-504.

[25] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, Hafez in Love, 23.

[26] Fassihi, “Iraj Pezeshkzad.”

[27] Pezeshkzad, “Delayed Consequences.”

[28] Iraj Pezeshkzad, Khānavādah-yi nīk’akhtar [The Nik-Akhtar family] (Tehran: Ketab-e Abi Publishing House, 2001).

[29] Dominic Brookshaw, Hafiz and His Contemporaries: Poetry, Performance and Patronage in Fourteenth-Century Iran (London: I. B. Tauris, 2019).

[30] Dick Davis, trans., Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (New York: Penguin Books, 2013).

[31] Geoffrey Squires, trans., Hafez: Translations and Interpretations of the Ghazals (Miami, FL: Miami University Press, 2014).

[32] Elizabeth A. Gray and Iraj Anvar, Wine and Prayer: Eighty Ghazals from the Divan of Hafiz (Ashland, OR: White Cloud Press, 2019).

[33] Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn, trans., The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2008).

[34] Kayhan London, “In Commemoration of Iraj Pezeshkzad: This Playful Hafez,” News and Views for a Global Iranian Community, https://kayhan.london/fa/1400/11/03/270528/, accessed September 3, 2022.

[35] Shabani-Jadidi and Higgins, Hafez in Love, 108.

[36] Iraj Pezeshkzad, Adab-i mard bih zi dawlat-i ūst taḥrīr shud [One’s manners outdo one’s wealth] (Tehran: Safi Ali Shah Publishing House, 2002).

[37] Iraj Pezeshkzad,Ṭanz-i fākhir-i Sa’dī [The elegant satire of Sa‘di] (Tehran: Shahab Saqeb Publishers, 2002).

[38] Shabani and Higgins, Hafez in Love, 42.

[39] The Modern Novel, “Iraj Pezeshkzad.”

[40] Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, Review, https://press.syr.edu/supressbooks/3471/hafez-in-love/, accessed September 3, 2022.

[41] M. A. Orthofer, The Complete Review, https://www.completereview.com/reviews/iran/pezeshkzad.htm, accessed September 3, 2022.