Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis, 1967-1977

Mahasti Afshar <azmahasti@gmail.com> studied drama, film and classical music production in London (BBC) and Paris (ORTF), and while on staff at NITV/NIRT, recorded live performances at the Shiraz Arts Festival for later broadcasting on TV. She earned a PhD in Sanskrit and Indo-European Folklore and Mythology (Harvard 1988) and pursued a career as a nonprofit arts and culture executive at the Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles Philharmonic Association, and National Geographic Society. She has published books and produced museum exhibitions and video documentaries on humanity’s archeological and historical heritage in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, Central and South America, and on the landmarks of a new generation in the U.S.

OVERVIEW

11th Festival, 1977. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

The Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of Arts was an international festival held in Iran every summer from 1967-1977. Jashn-e Honar-e Shiraz, as it was popularly known in Persian was an inspired and feverish exploration, experimentation and creative conversation between Iran and the outside world that unfolded primarily through music, drama, dance and film. Presented in Shiraz, or forty miles northeast at the Achaemenid ruins of Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rostam, the programs started at 10 a.m. every day and concluded at 1 or 2 a.m. the next, staggered across ancient, medieval and modern venues, some natural, some formal, others makeshift. True to its mission, the festival’s ecosystem cut across time and other boundaries, refreshing the traditional, celebrating the classical, nurturing the experimental, and stimulating a dialogue across generations, cultures, and languages, East and West, North and South.

Shiraz, “without doubt the most important performing arts event in the world…”[1] to cite one of many such accolades by foreign critics, was where most Iranians first encountered the traditional arts of Asia, Africa and Latin America—Indian raga music, Bharatanatyam and Kathakali, Qawwali, the music of Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Korea and Vietnam, Balinese Gamelan, Japanese Nôh, Rwandan drumming, traditional dances of Bhutan, Senegal, Uganda, and Brazil… The experience was eye opening, expansive, magical, and transformative. Or to use terms coined by Vali Mahlouji in his penetrating analysis, the festival was a “third-world re-writing,” a “temporary autonomous zone,” and “a universalizing heterotopia.”[2]

Persepolis, Takht-e Jamshid. Photo: Alireza Pourhassan

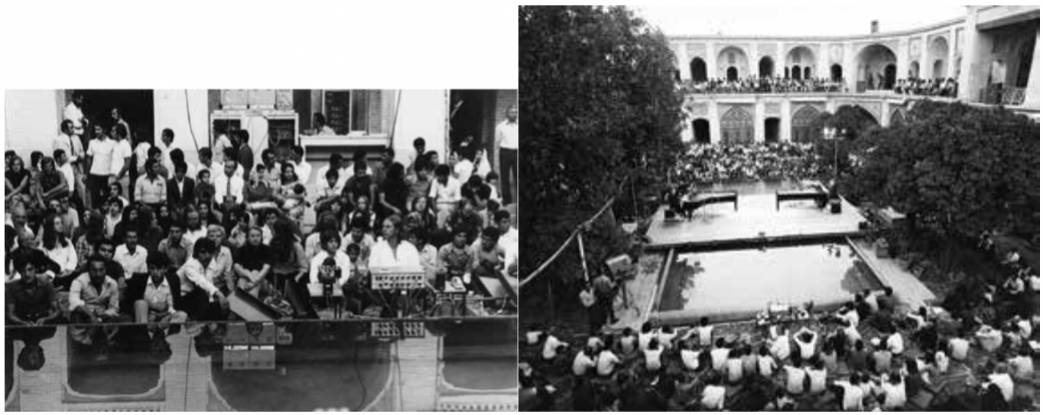

Shiraz is where Iranians came to “rediscover” their own traditional music on a different platform. Presented by master musicians on an international stage before large audiences for the first time, this exquisite art form acquired a fresh vitality and just recognition and gained new fans, especially among youth. Regional music from the four corners of the country was also presented at the festival, with the same result. And that is not all. It is at the Shiraz Arts Festival that Iranian audiences witnessed the revival of Persian storytelling and dramatic traditions on a large scale, naqqali, ta’zieh/shabih-khani and ruhowzi, celebrated a new generation of Iranian filmmakers along with cinema legends from East and West, and watched the spectacular birth of new Iranian theatre—playwrights, directors, and actors fearlessly writing and staging innovative plays in Persian that for the first time resonated globally. Owing to Shiraz, Iranian productions were invited to festivals in the West for the first time. Abbas Nalbandian’s play, Pazhuheshi…,[3] appeared at the Royan Festival and Esma’il Khalaj’s Shabat, at Nancy; Royan also presented the National Iranian Television Chamber Orchestra where it premiered Alireza Mashayekhi’s Permanent, and later, classical Iranian musicians Ali-Asghar Bahari, Farhang Sharif and Jamshid Shemirani. Another Western discovery was Hossein Malek who was invited to the Pamplona Festival in Spain.

A distinguishing feature of the Shiraz Arts Festival was the variety of works it commissioned from pioneers of contemporary music as well as representatives of avant-garde theater and dance, works that embodying a transcendent blend of East and West, were shaped by the landscape for which they were created. These were, in music, Iannis Xenakis’ Persephassa[4] and Persepolis (1969 and 1971, respectively), and Bruno Maderna’s Ausstrahlung, a spiritual journey through history that integrated recitations of Persian poetry (1971); in theatre, Peter Brook’s Orghast, a “work in progress” (1970) that involved actors of diverse nationalities, Iranians among them, speaking an invented idiom that included Avestan, Greek and Latin; and in 1972, Robert [Bob] Wilson’s KA MOUNTAIN… which ran non-stop for seven days and nights on a hill at Haft-tan with the participation of American and Iranian actors and nonprofessional locals; and last but not least, in dance, Maurice Béjart’s Golestan (1973), named after Sa’di-e Shirazi’s 13th century literary masterpiece and choreographed entirely on Iranian music.

Tens of thousands of admiring spectators experienced the festival each year on site. Millions more had the opportunity to watch the recorded programs on national television throughout the year. The festival operated on a starting indie budget of $100,000 that grew to $700,000 in 1977. The budget was subsidized in part by the state but mostly by the National Iranian Radio and Television (NITV/NIRT),[5] which offset its costs by airing the programs as part of its broadcast schedule. Ticket sales generated some revenue; most travel costs for foreign artists were taken up by governments that had bilateral treaties with Iran. The artists, thrilled by the opportunity to explore and innovate in a singular environment accepted minimum fees for commissioned work, and many offered world premieres of their works gratis.

To be sure, the festival’s fans, artists, and organizers represented a minority of the general population in Iran; the majority had little or no awareness of, interest in, or access to the likes of Balachander, Béjart, and Bijan Mofid. But that was precisely the point, to bring down the wall between the culturally privileged and underprivileged, and to celebrate and share humanity’s artistic wealth as widely as possible for the benefit of larger publics across the country, especially the younger generation. Many dream of making the world a better place; some dare to act on their dreams. Others slumber in the luxury of stagnation. Jashn-e Honar never slept.

Shiraz Festival catalogue, 1976. Qobad Shiva and Fowzi Tehrani

Formation, Mission and Organization

The idea for organizing an international festival designed to “nurture the arts, pay tribute to the nation’s traditional arts and raise cultural standards in Iran” and to furthermore “ensure wider appreciation of the work of Iranian artists, introduce foreign artists to Iran, and acquaint the Iranian public with the latest creative developments of other countries”[6] originated in 1966 with Queen Farah Pahlavi, the Shahbanou in Persian. The responsibility for shaping and executing the concept was delegated to Reza Ghotbi, then project manager for television at the Plan Organization, later director general of NITV.

Shahbanou Farah with Maurice Béjart, Shiraz Arts Festival

An advisory board was formed that charted the festival’s scope and principal goals. In Ghotbi’s words, the festival would present all the arts “in the context of an encounter between East and West” with a focus on “the best traditional arts of the East, the finest classical traditions of the West, and the avant-garde apropos its place in the world.”[7] The festival would also undertake research and pursue activities in the creative domain.[8]

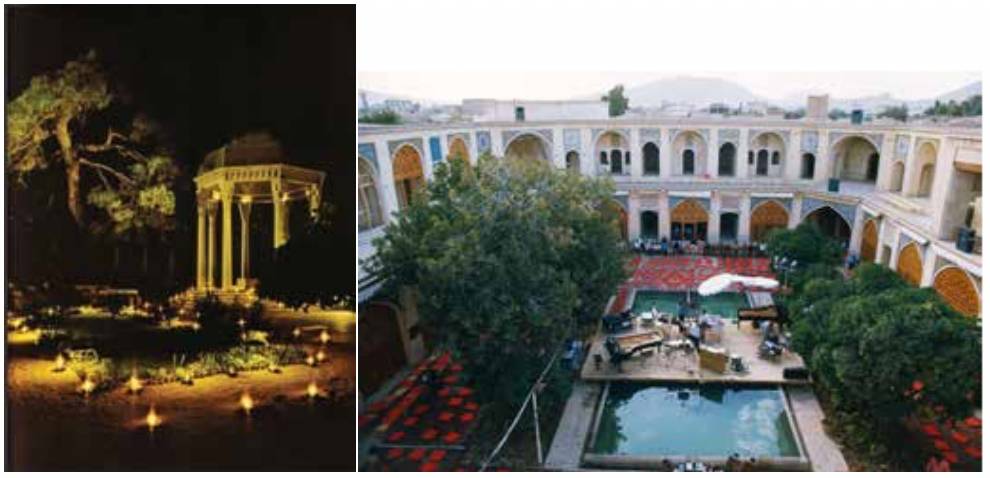

Most cultural activity being centered in Tehran, the group decided to host the festival away from the capital thinking that the effort to make the trip and the concentration of artists and festival-goers in one location would enrich the experience, “like an artistic pilgrimage.” After considering Kashan and Isfahan, their choice fell on Shiraz. The city offered a variety of venues, among them, Hafezieh, the Delgosha Garden, Saray-e Moshir, Narenjestan, and the Jahan-Nama Garden. The Mehmansara provided hotel accommodation—modest, but adequate and in line with the festival’s identity—as did the newly built Pahlavi University student dormitories.

Hafezieh; Lighting design and photo: Keyvan Khosrovani / Sara-ye Moshir before a concert

To govern the festival, a 31-member board of trustees was formed under the patronage of Shahbanou Farah comprised of cabinet members, university chancellors, provincial authorities and other officials, and individual scholars, cultural figures, and custodians of properties earmarked as performance venues. The trustees, who served for two-year terms and who changed over time were responsible for approving the budget and the bylaws, nominating the board of directors, and appointing an inspector for financial oversight. A five-member board of directors was then appointed; Dr. Mehdi Boushehri served as President, with Reza Ghotbi, (NITV- and Festival Director General), and Farrokh Gaffary (NITV- and Festival Deputy Director General), Dr. Qassem Reza’i, Director, Tourism Organization, and Dr. Zaven Hakopian, Director General, Ministry of Culture and Arts. The Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis officially opened on 11 September 1967 (20 Shahrivar 1346), less than a year after NITV televised its first program.

Program Selection and Planning Process

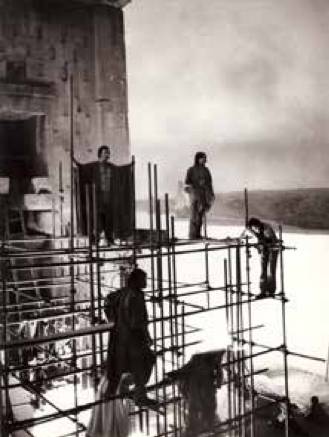

Planning and decision making were a collaborative team effort involving many individuals, principally, Ghotbi, Gaffary (the festival’s artistic director and later its de facto director); Bijan Saffari and [until 1971] Khojasteh Kia (theatre); and Sheherazade Afshar (music and dance); Gaffary was also in charge of film, and later, of theatre. Other key members of the team included Parvin Qoraishi (executive secretary), Faramarz Shahbakhti (administrator), Vardkes Esra’ili (engineering), Mohammad Shafa’i (construction workshop), Farideh Gohari and Fereshteh Shafa’i (set design), Keyvan Khosrovani (lighting design, inaugural year),[9] Manouchehr Shamsa’i (lighting), Yousef Shahab (sound), and Qobad Shiva (graphics). Publications, media and public relations posts were held by Iraj Gorgin and later, Karim Emami. Over the years, the festival benefitted from the advice and expertise of a large number of individuals, including Dr. Hormoz Farhat, Dr. Dariush Safvat, Fozieh Majd, and Houshang Ebtehaj (music), and Arby Ovanessian, Davoud Rashidi, Mohammad-Baqer Ghaffari and Parviz Sayyad (theatre).

5th Festival of Arts, 1969. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

Archives

Magnetic videotapes of most performances at the festival and a complete audio archive of the daily public forums and seminars with the artists, as well as interviews with the artists on 16mm film, were housed at NIRT as were festival catalogues, daily news bulletins, printed programs of each event, publications on music, drama, film and filmmakers, texts of plays, and the weekly Tamasha magazine. The archive also housed photographic prints and negatives, including some of the images created by Kamran Adle, Jean-François Camp, Ali Qashqai, Shahram Golparian, Abbas Hojatpanah, Bahman Jalali, Mehdi Khansari, Ata Kiani, Fou’ad Najafzadeh, Mehdi Seifolmoluki, Ali Rahbar, and Maryam Zandi.[10]

Daily public forum, 1970; L-R: Erika Munk, Raymonde Temkine (hidden), Jerzy Grotowski, Núria Espert, Arby Ovanessian, Karim Mojtahedi (standing, moderator)

Collectively, this archive formed a time capsule of substantial historical and cultural value, both in terms of Iran and internationally, covering the period 1967-1977. Portions of the archival material were destroyed soon after 1979 while some made it abroad. The catalogues can be found in major public and university libraries in the U.S.A. and Europe. Tamasha magazine has been since digitized in Iran by the Majles Library and is available on Data DVD. The state, nature and location of other items that may have survived is not known.

Shiraz Festival stamp, 1st day issue, 1972

PROGRAMS

Music

Traditional Iranian Music

Iranian classical or traditional music, musiqi-ye aseel (“authentic” or “noble” music), which is Iran’s highest and most treasured performing art—as is poetry in the literary domain and miniature painting in the visual—was the heart and core of the festival’s programming. Several concerts were offered each year in Hafezieh, an ideal setting where Hafez, a 14th century native of Shiraz who is considered Iran’s greatest lyric poet of all time lies in a white marble tomb etched with his memorable verses under the shade of a stepped, open pavilion in a jasmine-scented garden.

7th Shiraz Festival, 1973. Poster design: Fereydoun Ave

Beginning in 1967 and through 1977, the most distinguished masters of traditional Iranian music were selected in close collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and Arts, Radio Iran, and NITV to appear at the festival. The general public knew these masters primarily through radio while a privileged few enjoyed live performances hosted by small circles of aficionados in their private homes. Meantime, the market for popular music was growing exponentially. As part of the trend, classical musicians were led to play the modal systems (dastgahs) in shortened forms that fit radio program schedules and were more palatable for public consumption. The festival, on the other hand, was a platform where live concerts were performed full scale on a formal, international stage before large audiences. The pioneering effort was transformative, such that prominent artists who as a matter of course refrained from performing publicly agreed to appear at the festival, Saeed Hormozi, Yousef Foroutan, and Dariush Safvat, among them.

Four concerts were offered during the inaugural festival in 1967, with all seven major modes performed by the most renowned instrumentalists, among them, Ali-Akbar Shahnazi (tar), Ahmad Ebadi (setar), Jalil Shahnaz (tar), Hassan Kassa’i (ney), Lotfollah Majd (tar), Faramarz Payvar (santour), Ali-Asghar Bahari (kamancheh), Hossein Tehrani (tombak), and vocalists, Hossein Qavami, Mahmoud Karimi, Touraj Kiarass and Khatereh Parvaneh.

Jalil Shahnaz, Ali-Asghar Bahari, Hafezieh, 1973. Photos: Jean-François Camp

L-R: Faramarz Payvar, Hossein Tehrani

News of the event spread around town by word of mouth and through public media. The concert on the second night played to a packed, standing-room only audience with spectators lined up all the way back against the garden rails. From then on, on nights when the adjacent site, Hafezieh Stadium, was free, the music was amplified over the garden walls to the delight of non-ticketed publics who gathered outside to listen. Numerous other recognized masters also appeared in concert over the life of the festival, including Abdolvahab Shahidi, Taj Esfahani, Mahmoudi Khonsari, singers, and Gholam-Hossein Bigjekhani (tar), accompanied by Mahmoud Farnam (daf), Farhang Sharif (tar), and Hossein Malek (santour).

The festival’s goal—which was achieved at the outset and sustained to the end— had been to present unadulterated, authentic Iranian music with the respect due the art and its foremost exponents. As a result, not only countless more Iranians came to appreciate their own traditions, but foreign critics posted reviews of Iranian music in the international press with the same level of interest and esteem accorded classical Indian, Chinese and Japanese music.

L-R: Shemirani, Bahari, Shajarian, Bigjekhani, 1973. Photos: Jean-François Camp

In subsequent years, a new generation of gifted artists joined the roster of musicians that appeared at Jashn-e Honar, while NIRT’s Center for the Preservation and Propagation of Music (Markaz-e Hefz va Esha’eh Musiqi), established in 1968 under the direction of Dr. Dariush Safvat, contributed new research, training, and programming. A new standard was set with the introduction of young masters at the festival, Dariush Tala’i and Hossein Alizadeh (tar and setar), Mohammad-Reza Lotfi (tar), Jalal Zolfonoun (setar), Majid Kiani and Parviz Meshkatian (santour), Jamshid Shemirani (tombak), and singers, Siavosh (Mohammad-Reza) Shajarian, Noureddin Razavi-Sarvestani, and Parisa, all of whom were enthusiastically received by audiences and critics alike.[11]

Parisa at Hafezieh, 1976.

Watching two generations of musicians bring the exquisite spirit of traditional Iranian music to life side by side was to experience the sublime; it refreshed the art, artists and audiences alike, as if in a nod to Hafez’s verse, “I may be old, but hold me tight in your arms one night and I’ll wake up young by your side at dawn”:

گر چه پیرم، تو شبی تنگ در آغوشم کش

تا سحرگه ز کنار تو جوان بر خیزم

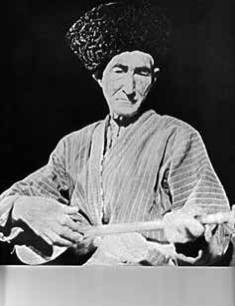

The festival also presented regional Iranian music, which although prized locally was not considered a fine art, nationally. A shift in perception of this genre of music started with the appearance of Asheqs from Azarbaijan and musicians from Kurdistan in the early years of the festival, while a dramatic rise in its stature became palpable beginning in 1973 as the “NIRT Center for the Collection and Study of Regional Music”[12] founded under the direction of Fozieh Majd contributed more varieties of programs to the festival. Master “singers of tales” from Baluchestan, Khorasan and the Persian Gulf, none of whom had ever performed outside their region, found an audience mesmerized by a repertoire that ranged from meditative and mystical poetry to epic and romance. Collectively, they broadened the horizon of Iranian music and its audience in ways unimaginable before.

Highlights of the regional music, instruments, and artists from Khorasan included Nazar-Mohammad Soleymani (dotar) and vocalist Morad-Ali Salar-Ahmadi who by popular demand performed again the next evening; dotar players and singers, Mohammad-Hossein Yeganeh who performed the tale of the Sufi king, Ebrahim Adham, and Olia-Qoli Yeganeh who performed Gharib and Shah Sanam, the romance of Zohreh and Taher and songs from the Kour Oqli cycle. “Sha’eri, Baluchi Epic Tales in Song and Music” was performed by La’l Baksh Peyk (vocals and tanbireh), accompanied by Qolam-Heydar Baluch on the sorud (bowed string instrument). Also, from Baluchestan, the festival hosted Guati Music led by Karimbaksh Ostadi, principal singer and tanbireh player; as well as a Noban and Zar healing ritual from the Persian Gulf island of Qeshm, with Baba Darvish and Mama Hanifa, Zar leaders.

The events were a sensation from start to finish.

Olia-Qoli Yeganeh, 1975

Noban and Zar, 1973; Mama Hanifeh (R). Photos: Jean-François Camp

Traditional Eastern and African Music

Iran and India share ancient cultural roots that are expressed in their respective sacred literatures, the Avesta and the Vedas. In later periods, Iranians were exposed to Hindu literary traditions when the Mughal Empire produced Persian translations of the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and other Sanskrit literature starting in the 16th century. Farther east, Iranians learned of the arts and crafts of China and other lands that traded along the Silk Road. Literary and visual arts aside, however, Iranians had no firsthand experience of the performing arts of Asia. The Shiraz festival introduced audiences to a vast array of traditional music, dance and dance-drama from Indonesia to the Philippines, Japan, China, and across the Middle East and Africa, that went a long way to filling the void.

The master instrumentalists who first introduced the gift of Bhairavi, Darbari, and other grand ragas of classical Indian music to the audience in Shiraz included the great Vilayat Khan, sitar, and Sharan Rani, sarod (both in 1967), and Bismillah Khan, shehnai (1968). Audience reaction went from initial astonishment and curiosity to a little impatience, and in rapid resolution, to absolute awe, where it settled for the lifetime of the festival.

3rd Shiraz Festival, 1969. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

In 1969, the year when percussion was the theme, the festival hosted Shiv Kumar Sharma, santoor (Indian dulcimer), Debabrata Chaudhuri, sitar, and Doreswamy Iyengar, veena, who performed with Trichy Sankaran, mridangam. Sitar players Imrat Khan and Ravi Shankar were hosted in 1970, the latter accompanied by Alla Rakha on the tabla; Balachander, veena, performed at the festival twice, in 1970 and again in 1976. Other eminent instrumentalists from India included, in 1973, Amjad Ali Khan, sarod, and Ram Narayan, sarangi, and in 1975, Hariprasad Chaurasia, whose bansuri, the storied bamboo flute known as Lord Krishna’s divine instrument, left the audience spellbound.

Ravi Shankar, Persepolis, 1970.

Classical Indian vocal music was performed, among others, by Pran Nath, a master of Kirana Gharana known for his austere singing style (1974), and by Nasir Aminuddin Dagar, the pre-eminent exponent of the dhrupad (1976). The traditional Rajasthani art form, Pabuji Ki Phad, a scroll painting used by priests to sing songs of the heroic exploits of the folk deity, Pabuji, was also part of the vast repertoire of Indian music presented at the festival.

A short list of traditional music from East and Southeast Asia included, from Taiwan, Yi Chi Liu, performing on the pipa and yangqin, (1967), and Chien-Tai Chen, yangqin (Chinese dulcimer), plus three types of gamelan from Bali and Java, Indonesia (1969 and 1976). The festival also hosted Lhamo, a 400-year-old folk opera performed by exiled Tibetans from Dharamsala (1976). From Japan came Rinshoei Kida (shamisen), koto players Shinichi Yuize and Yori Kishibe (1968), Kinshi Tsuruta (biwa and vocals), and Katsuya Yokoyama, shakuhachi (1976), and from Vietnam, the great musician and teacher, Trần Văn Khê who appeared at five of the festivals performing on the dan co and dan tranh.

Trần Văn Khê (R) and son Trần Quang Hâi, 1975.

The festival also presented diverse genres of African, Middle Eastern, and West Asian traditional music. Highlights included a striking nine-man ensemble of drummers from Rwanda (1969); classical Arabic music was performed by Munir Bashir, the Iraqi master of the oud (1974); and Mahmoud Aziz led an ensemble performance of Tunisian liturgical music (1975). L’Ensemble Lyrique Traditionnel du Sénégal appeared in 1976 as did Aziz Mian, a master of Qawwali from Pakistan who mesmerized the audience with his rendition of Sufi devotional music. Finally, one may mention the Musicians of the Nile Delta, led by Metqal Qenawi Metqal, who brought spiritual folk chants from Upper Egypt to the festival in 1977.

Rwandan drummers, 1969

Western Music

Classical Western music had almost a century-old history in Iran and a serious, if relatively small group of adepts mostly concentrated in the capital. The festival’s mission in this category was to offer the finest of the classical repertoire and also make known the best in the contemporary and the avant-garde.

The quality of sound production was exceptional. As reported by Financial Times lead music critic Andrew Porter, “Indeed here at Persepolis and in Hafezieh the ‘assisted’ open-air sound had a naturalness and trueness surpassing anything I have ever heard in the West”[13] a feat all the more remarkable in view of the range and variety of programs and instruments, both Western and Eastern, from solo recitals to orchestral and choral, including electro-acoustic music and musique concrète.

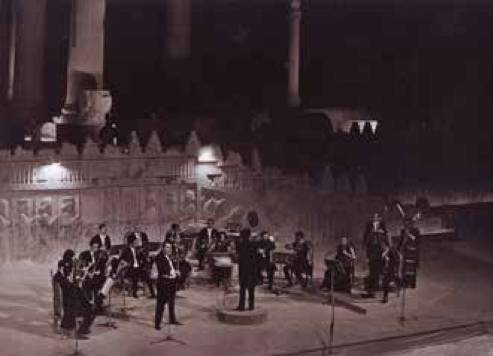

The inaugural year in 1967 opened with a concert by the National Iranian Television Chamber Orchestra[14] (est. 1967) conducted by Vahe Khochayan in a performance of Pergolesi’s Salve Regina with Iranian soprano, Nasrin Azarmi, and ended with the world premiere of Kakuti, a dance for her by Iranian composer Morteza Hannaneh. Yehudi Menuhin was the soloist for the orchestra’s second concert at Persepolis; piano recitals were offered by Ayşegül Sarica, Elzbieta Glabowna and Novin Afrouz in the same year. The final event was a concert by the L’Orchestre du Domaine Musical led by Gilbert Amy in a program of Varèse, Messiaen, and Mozart, and the world premiere of Amy’s Relais.

Yehudi Menuhin with the NITV Chamber Orchestra, 1967

A selective list of notable musicians in 1968 includes Arthur Rubinstein performing works from the classical repertoire, Iván Eröd, Hindemith, and works from the Second Viennese School; and Cathy Berberian, Berio, and her own composition, Stripsody. The closing event featured the NITV Chamber Orchestra at Persepolis, Farhad Mechkat conductor, Christian Ferras, violin, performing world premieres of works by Hormoz Farhat, Morteza Hannaneh, and Houshang Ostovar.

NITV Chamber Orchestra with Mechkat and Ferras, 1968

In 1969, Martha Argerich was featured in a recital of works by Bach, Debussy and Chopin, and Yvonne Loriod performed Chopin, Albeniz and Messiaen, and a Mozart concerto with the l’Orchestre National de l’ORTF. The third festival also presented the world premiere of Xenakis’ Persephassa, which echoed that year’s central theme, “percussion.” Performed by Les Percussions de Strasbourg in Persepolis, the work featured six musicians stationed on widely separated platforms playing a wide range of percussive instruments as the audience moved about, with the space itself acting as an instrument of music. The ensemble also offered a concert that included the world premiere of Betsy Jolas’s États: pour violon et six percussions. The latter two compositions were co-commissioned with the French Ministry of Culture. The ORTF orchestra performed other concerts in 1969 as well; the programs included Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique and Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, led by Jean Martinon, and Messiaen’s Et Exspecto Resurrectionem Mortuorum, a work commemorating those who died in the two World Wars, conducted by Bruno Maderna in the presence of the composer. The Juilliard Quartet was featured in the 4th festival in 1970 in a performance of works by Beethoven, Webern and Bartok.

R-L: Olivier Messiaen, Bruno Maderna, Jean Martinon, 1969. Photo: Jean-François Camp

The world premieres of Xenakis’ Persepolis and Bruno Maderna’s Ausstrahlung—both festival commissions—were presented in 1971. The latter was performed by The Hague Residence Orchestra led by Maderna himself with soloists Berberian, Verheul and Faber. Iranian conductor Farhad Mechkat also led the same orchestra in a program that ranged from Baroque to contemporary music. The Moscow Chamber Orchestra conducted by Barshai also appeared in 1971 as did the Cracow Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir in concerts led by Katlewicz. John Cage, David Tudor and Gordon Mumma appeared in concert at the 6th festival in 1972 and collaborated with Merce Cunningham in separate programs in the same year.

John Cage at the public forum, 1972 / Cage and Gordon Mumma (L)

One special program was a week-long Stockhausen retrospective in 1972. Students turned out in droves at Saray-e Moshir, squatting on the floor in shirt sleeves and jeans to hear him, with many locals looking in, fascinated by the novelty of the music and the production.

Stockhausen at the sound desk, 1972 / Stockhausen concert, Sara-ye Moshir, 1972

At Delgosha Garden where he performed his Sternklang the crowd almost got out of hand as they overflowed the space and climbed telegraph poles to get a better look, an image emblematic of the festival whose audience grew increasingly young and engaged, presumably because they heard the music in an environment that encouraged openness, curiosity, exploration, and level participation with the rest of the world through the arts. To say that foreign artists and visitors were just as excited by their experience in Shiraz is an understatement. Mumma described the 1972 festival as “one of the most extraordinary cultural experiences of my life.”[15]

The 1974 festival featured the London Sinfonietta with David Atherton and Mary Thomas, and in 1975, the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, led by Penderecki conducting his own compositions, and by Maksymiuk in performances of Ravel and Mussorgsky.

Penderecki at Persepolis, 1975

In 1976, the American Brass Quintet offered a rich program of music that ranged from the 16th century to Elliot Carter and Gilbert Amy and performed the world premiere of Contradictions by Iranian composer Alireza Mashayekhi. Another world premiere that year was Iranian Set by Bogulaw Schäffer, a work based on Persian poetry, with Adam Kaczynski leading Ensemble MW2. The 11th festival in 1977 featured the composer Morton Feldman and the Creative Associates. Iranian composers whose work premiered in the course of the festival[16] included Dariush Dolatshahi, Fozieh Majd, Mohammad-Taghi Massoudieh, Massoud Pourfarrokh, Manouchehr Sahba’i, and as mentioned earlier, Hormoz Farhat and Houshang Ostovar.

In 1969, American jazz and blues programs featured the great jazz drummer Max Roach leading his Quintet, and the vocalist and songwriter Abbey Lincoln; and in 1970, the gospel, soul and R&B group, the Staple Singers.

Max Roach Quintet, 1969

Dance and Music Theatre

Iran has no indigenous tradition of formal dance, only folkloric. Discovering the breathtaking variety of traditional and modern dance from around the world at the festival was therefore a novel adventure for the audience. Classical Indian dance was presented in all its varieties, beginning with a Kathakali performance of the Ramayana and Mahabharata in 1968. Among the foremost exponents of Indian dance forms were Uma Sharma who performed Kathak in 1969; Yamini Krishnamurti and Sonal Mansingh, Kuchipudi and Odissi (1970), and Shanta Rao, Bharatanatyam, Mohiniattam, Bhama Nrityam and Kathakali dances (1972).

2nd Shiraz Festival, 1968. Poster design: Houshang Kazemi

The opening program in 1972—a festival commission—was a Kathakali presentation of Rostam and Sohrab, a fabled tragedy where the greatest hero in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the 10th century Persian national epic, mortally wounds his son in battle, neither man being aware of the other’s identity until it is too late. Other Indian dance programs included Sanjukta Panigrahi performing Nritta and Odissi, her signature dance form (1975), and Purulia Chhau, a tribal martial dance popular in regional festivals in India, particularly in West Bengal, which was presented in the 11th festival in 1977.

Top: Kathakali, 1968. Bottom: Rostam o Sohrab, Persepolis, 1972

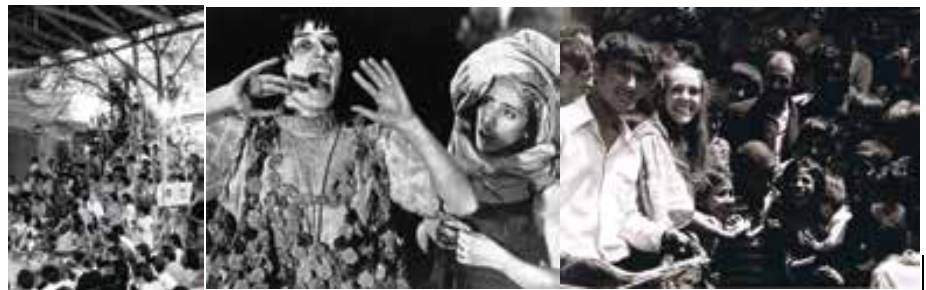

An array of Indonesian dance and music drama also dazzled at the festival. One particularly memorable Balinese program was the opening event in 1969, the story of Rama’s struggle to rescue his wife Sita from the clutches of the demon Ravana. The highly stylized choreography, with the dancers’ arms, fingers, and facial expressions moving to the strange and hypnotic beat of the gamelan framed by lush colors and elaborate costumes conjured an unreal, timeless and dreamlike dimension at Persepolis. Another rousing performance was a Balinese Kechak at Naqsh-e Rostam in 1976. Presented by Sardono W. Kusumo, it featured a percussive a cappella chorus of men and boys in checkered waistcloths hunched down in tight circles chanting “chak-chak” and throwing up their arms as they voiced a battle from the Ramayana.

Top: The Ramayana, Persepolis 1968. Bottom: Balinese Gamelan and Legong Dance, 1969

The festival’s complement of dance and music theatre also included Chham, sacred and ancient Buddhist dances from Bhutan, and Brazilian Capoeira, a ritualistic fusion of martial arts, dance, and music in 1974, and along with the Senegalese National Ballet (1970), a number of African productions derived from indigenous traditions that included Duro Lapido’s Oba-Koso from Nigeria (1973) and in 1975, Robert Serumaga’s dance-drama, Renga Moi from Uganda.

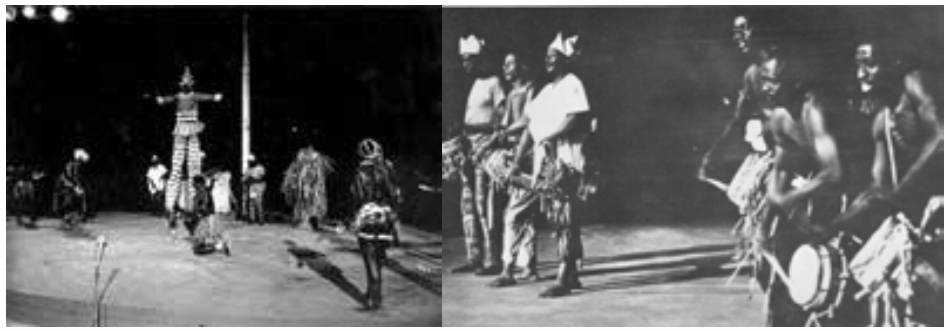

National Ballet of Senegal and musicians, 1970

Oba-Koso, Nigeria, 1973. Photos: Jean-François Camp

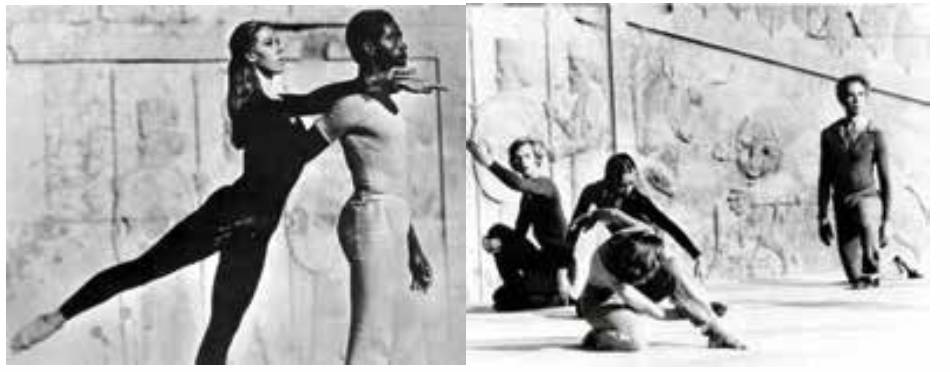

Western modern dance was represented by several choreographers and dancers at the forefront of the avant-garde. In 1972, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company presented “Open Air Theatre Event,” described by one critic as “an incredible soaring of pure spirit,”[17] followed by the world premiere of “Persepolis Event.” Carolyn Brown, one of the dancers remembers the experience as “marvelous” and “unforgettable.”[18]

Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Persepolis, 1972. Photos: Abbas Hojatpanah

The opening program of the 7th festival in 1973 was the world premiere of Maurice Béjart’s Golestan at Persepolis, a work named after a Persian literary masterpiece by the 13th century poet Sa’di who says of his own work, “A rose lives a mere five or six days/The joy of my rose garden abides forever,” and performed by the Ballet du XXe Siècle. The dance was set to Iranian music performed live by members of the NIRT Center for the Preservation and Propagation of Iranian Music. Béjart’s Improvisation sur Mallarmé III, a work based on music by Boulez was also premiered that year. Back in Belgium, he created Farah at his own initiative, a work inspired by Rumi and other Persian mystical poetry. He invited the Iranian musicians who had accompanied his Golestan in Shiraz to premiere the work in Brussels and performed it in many major European cities and at the 10th festival. Béjart’s premiere of Héliogabale was also on the program in 1976 as were his L’Oiseau du feu and Le Sacre du Printemps.

Maurice Béjart, Golestan, 1973

The Nikolais Dance Company, led by founder and renowned American choreographer, Alwin Nikolais, gave the opening night performance of the 9th festival in 1975 with a program that included Temple, and Tribe- Dance I & II.

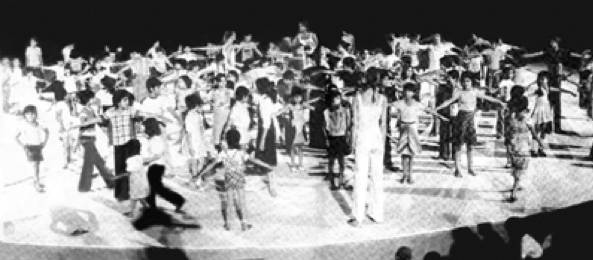

In 1977, the festival hosted the world premiere of Carolyn Carlson’s Human called Being at Naqsh-e Rostam. In the same year, Carlson also performed her trilogy, This; That; The Other and conducted a special workshop for children.

Carolyn Carson, This; That, The Other, 1977

Carlson workshop for children, Jahan-Nama Garden

Theatre

From 1967-77, the Shiraz Arts Festival presented more than fifty traditional as well as contemporary and experimental plays from Iran, India, Japan, Eastern and Western Europe, Africa, U.S.A., and Latin America, and accommodated a number of independent “ancillary” productions, including popular Iranian theatre.[19]

Traditional Iranian Theatre

In terms of Iran, the festival had a twofold goal. One was to revitalize indigenous Iranian dramatic arts, and the other, to stimulate the growth of theatre in Iran and propel it to international standards. The indigenous Iranian dramatic arts constitute naqqali, a storytelling tradition involving dramatic recitations of Persian epic poetry and other narrative literature; ta’zieh (also known as shabih- khani), a Shi’ite Passion play or mourning ritual commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Hossein at the battle of Karbala in 680 C.E.; and ruhowzi, popular drama imbued with social satire.

With eyes on its first goal, the 1967 inaugural festival presented a series of performances featuring some of the most notable naqqals in the country. In the same year, Parviz Sayyad presented Ta’zieh Horr, Nemayesh-e Kohan-e Irani (Ancient Iranian Theatre), the first such public enactment outside rural areas since ta’zieh performances were banned in 1933. Following its warm public reception, Sayyad produced Ta’zieh Moslem in 1970, and in 1971, Khorouj-e Mokhtar, a tale centered on revenge—with comic overtones and no martyrs— that is traditionally performed on the 13th of Muharram to provide relief after ten days of mourning. In 1976, Mohammad-Baqer Ghaffari who had traveled for a year and a half in search of ta’zieh performers and musicians produced seven ta’ziehs at Hosseinieh Moshir in Shiraz and in the village of Kaftarak nearby where about 10,000 spectators attended free of charge. In the same year, the festival hosted an international seminar on ta’zieh chaired by Peter Chelkowski, where approaching ta’zieh as pure drama and presenting it outside a religious/ritualistic context was a subject of lively, and as yet unsettled discussion and debate.

Ta’zieh: karna players, performance, children’s choir, 1967

Ta’zieh at Kaftarak, 1976

Ta’zieh Conference, 1976. Poster design: Leyly Matine-Daftari

Ta’zieh left an impression on some foreign directors, notably on Peter Brook who in spring 1970 had seen a spartan performance of Ta’zieh Moslem in Abdullahabad, a village near Neishapur in Khorasan, and was struck by the dramatic effectiveness of its technique.

The festival’s interest in exploring and presenting traditional Iranian theatre included a ruhowzi festival and seminar at the 11th festival in 1977.

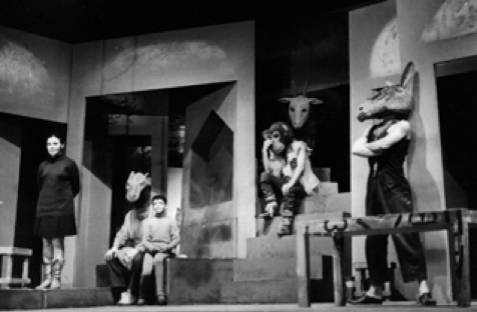

Contemporary Iranian Theatre[20]

To address its second goal, namely, to cultivate and advance the dramatic arts in Iran, the Shiraz Arts Festival launched a playwriting competition in 1967 that in 1969 led to the founding of NIRT’s Theatre Workshop, Kargah-e Nemayesh, led by Bijan Saffari, whose mission, to “help writers, actors, directors and designers exercise and experiment independent of commonly accepted professional restrictions,” operated in close association with the festival.

The first hidden talent to emerge from the competition was Abbas Nalbandian, a 21-year-old newspaper seller whose Pazhuheshi…, written two years earlier, had been rejected by other production companies as “un-stageable.” The play depicts eight already dead characters who “search, get acquainted, travel, exchange ideas, make a show of their lives, die, get resurrected, and keep going without getting anywhere,” confronted by a “director” and his twelve “assistants” who threaten to install central heating if the actors fail to perform well. In staging Pazhuheshi at the 1968 festival, Arby Ovanessian who also designed the set, costumes and lighting, acted not as a mere stage-master but as a master artist recreating another artist’s work as his own, a radical notion that opened the gates to the true art of directing in Iran. [21]

Pazhuheshi…, 1968

The second gifted playwright that emerged through the competition in 1968 was Mahin Jahanbegloo (Tajadod). A doctoral candidate in Persian literature, her Vis o Ramin, based on an 11th century romance by Fakhruddin Gorgani, underlined the wealth of Persian narrative poems that have rarely been exploited for their dramatic value. The play opened the 4th festival whose theme was “Theatre and Ritual.” Under Ovanessian’s direction, it was timed to unfold with the movement of the setting sun; he then lit a fire, a natural artifice with deep, spiritual undertones.

4th Festival, 1970. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

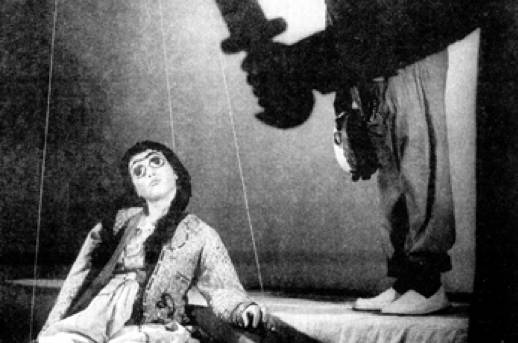

Vis o Ramin, 1970. Photo: Mehdi Khansari

In 1972, another Nalbandian/Ovanessian collaboration titled Nagahan ‘Haza Habibullah. . .’ (All at Once . . .)[22] offered an outstanding performance by Bijan Mofid in the lead role of a teacher who is murdered by his neighbors at high noon on ‘Ashura, the anniversary of the martyrdom of Imam Hossein, for a hidden treasure that turns out to be merely a chest full of books. The play is a commentary on the plight of societies that characterized by poverty, ignorance and superstition commit a tragic mistake and kill the source of knowledge, which is a universal path to salvation.[23]

Bijan Mofid (L) in Nagahan…, 1972. Photo: Jamileh Neda’i

Another highly acclaimed production in 1968 was Shahr-e Qesseh, a play in the vernacular genre written and staged by Bijan Mofid. A social commentary with animals representing familiar character types in Iranian society, the production was accompanied by moving songs composed and performed by Mofid himself that were soon memorized by one and all and are cherished today as a living legacy of this multi-talented and widely popular artist.

Shahr-e Qesseh, 1968

Iranian theatre continued to thrive at the festival, including a number of ancillary productions named here along with the official entries. In 1969, Mofid directed his Mah o Palang, a political allegory in which he played the leopard (“palang”). He returned to the festival in 1973 with a new play, Bozak Namir Bahar Miyad, a coproduction directed by Maria Krishna with her Théâtre Athanor from France that included French and Iranian actors and had both children and adults for an audience.

Bozak Namir Bahar Miyad, 1973

Another of his plays, Rubah o Oqab, was staged by his younger brother Ardavan Mofid in 1977 with actors from the Kanoon-e Parvaresh-e Fekri-ye Koudakan va Nojavanan (Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults).

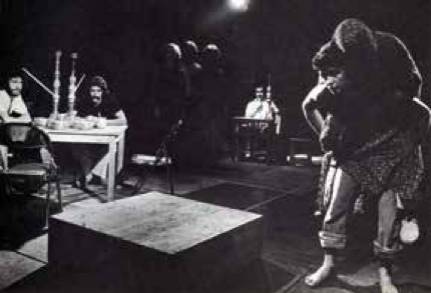

Other Iranian plays rich with local flavor, social commentary, poetic realism and currency were developed at the Theatre Workshop for the festival during 1972-1977. Among them were four plays by talented writer-director Esma’il Khalaj who staged his Halet Chetoreh Mash Rahim?, Goldouneh Khanoum, and Jom’e-Koshi in a tea house in Shiraz, and his widely acclaimed Shabat, which later traveled to Warsaw. Gifted writer, director, actor, and artist Ashurbanipal Babilla presented two of his works, Emshab Shab-e Mahtabe indoors, and Hora Sexta at Persepolis.

Halet Chetoreh Mash Rahim?, 1972

Jom’e-Koshi, 1973

Shabat, 1976

Hora Sexta, 1977

A number of veteran Iranian theatre directors appeared at the festival as well. The well-known and popular stage and TV director, writer and actor, Parviz Sayyad, previously noted for his productions of ta’zieh, staged a play in a tea house based on the merry “eavesdropping” seasonal rite, Falgoush, written by poet-artist Manouchehr Yekta’i that enjoyed a very warm reception. Another renowned actor and director, Abbas Javanmard, produced Bahram Beyzai’s Ghoroub dar Diyari Gharib and Qesse-ye Mah-e Penhan, two one-act puppet plays sponsored by the Ministry of Culture and Arts and performed by actors from the Gorouh-e Honar-e Melli (National Arts Group). A final example among veterans is the pioneering writer-director Ali Nassirian who staged his ruhowzi-inspired Bongah-e Teatral in Saray-e Moshir, which was also sponsored by the Ministry.

Ghoroub dar Diyari Gharib, 1973

Bongah-e Teatral, 1974

The festival also presented a new generation of Iranian directors that included Iraj Saghiri, a native of Bushehr in southern Iran who staged his Qalandar-Khouneh and Mahpalang, both richly inspired by local traditions and colors, Aziz Chitta’i who presented his Omar Khayyam dar New York with the Tokme Repertory Company that he had created in New York, and Mohammad Saleh-Ala who wrote and directed Zir-e Chador-e Oxygen, and Eski ru-ye Atash. Two other productions were supported by the Ministry of Culture and Arts: former member of the Theatre Workshop Shahru Kheradmand staged Rostam o Esfandiar, a tragedy of epic proportions that pits two iconic Shahnameh heroes against one another; and writer-director Mehdi Faqih presented his Bastur with a puppet theatre company from his native Fars Province.

Qalandar-Khouneh, 1975

The collective result was a paradigm shift that propelled Iranian theatre from a domestic stage to an international one.[24] Iranian plays were for the first time reviewed in foreign media—and favorably so—while Pazhuheshi… which became the subject of a doctoral dissertation[25] also made history by being the first Iranian play to be invited to international festivals. Another milestone was Ovanessian’s production of Albert Camus’ Caligula in 1974 where he cast the protagonist as a split personality played simultaneously by two actors. Hailed for its striking originality, the play was invited to tour Poland and was performed in Latin America, making Ovanessian the first Iranian to be invited to direct a foreign play in the West.

Caligula, 1974

For the Festival’s 10th anniversary in 1976, several artists were invited to come back to Shiraz with new creations. In response, the leftist Confederation of Iranian Students that rejected the festival as too liberal and the Iranian regime as too illiberal launched a concerted political campaign in Europe and the U.S.A. and pressured some of the Western artists who were eager to return to decline.

One positive response, however, was Savari Dar-amad … (There Appeared a Knight . . .).[26] Developed collectively— the first such experiment in Iran—with Mahin Jahanbegloo (Tajadod) as the lead writer,[27] the text incorporates the Younger Avesta, Manichean writings, classical Persian literature, Islamic mysticism, and Iranian Illuminationist philosophy as a composite expression of “Persian poetic wisdom,” and depicts the end of obscurity at the moment when, driven by greed, darkness swallows the light. A Knight was invited by the Theatre of Nations to represent Iran in Caracas, Venezuela in 1978; it was also presented at La MaMa in New York.

Savari Dar-amad, 1976

L-R: Brook, Ovanessian, Grotowski, 1970

Traditional Eastern and African Theatre

The festival presented more than a dozen varieties of non-Iranian traditional theatre over the years; most, if not all these exquisite art forms were unfamiliar to the audience in Shiraz and a true revelation. Several examples from the East and Africa were previously noted under Music Dance and Theatre, including Indian Kathakali, a Balinese rendition of the Ramayana, Oba-Koso, Yoruba musical drama from Nigeria (1973), and Robert Serumaga’s Renga Moi offered by the National Theatre of Uganda (1975). In addition to these, the festival hosted Wayang Kulit, shadow puppet theatre from Malaysia (1973), several presentations of Nôh, traditional Japanese lyrical drama (1975), and Bhavai, folk theatre from Gujarat (1977).

Contemporary and Experimental International Theatre

The most memorable foreign productions at the festival were presented starting in 1970 and numbered [then] Eastern Bloc (8); Western Europe (5); U.S.A. (10); Latin America (1), and Asia (2). Only Japan presented both experimental and traditional theatre at the festival.

Eastern and Central Europe

Poland set the tone of contemporary theatre at the festival in 1970 with one of the greatest theatrical works of the 20th century, Jerzy Grotowski’s The Constant Prince, a product of the director’s radical concepts, the “theatre laboratory” and “poor theatre.” Groups of fifty spectators seated inside the Delgosha Garden pavilion watched in awe and dread as Ryszard Cieslak enacted the anatomy of resistance, anguish and pain with perfect control over every muscle, sinews and vein in his body. The astounding quality of Grotowski’s work and his personal gravitas, palpable during the morning seminars and debates, imbued the festival with a heightened sense of intensity and drive. In 1973, another Polish director, Krzysztof Jasinski, staged Polish Dreambook and Fall with Teatr Stu from Cracow, and Atelier 212 from Yugoslavia performed Slobodanka Alexic’s Hamlet in the Cellar (1973) and Miracle in Shargan by Ljubomir Simovic, directed by Mira Trailovic´ (1976).

The Constant Prince, 1970

Two other works from Poland deserve special mention. In 1974, Lovelies and Dowdies, written by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz “Witkacy” in 1938, was stripped down and staged by another pioneering theatre director and theorist, Tadeusz Kantor, as an iteration of Impossible Theatre, a happening where the actors took shape on the spot and the spectators were dragged into the action. Kantor came back to the festival in 1977 to stage his most famous work, Dead Class; he played himself as a director in a classroom where the children are lonely marionettes and robotic adults who cannot relate to their childhood, ambiguous characters that endlessly morph, disintegrate, and finally harden in a dead class. Both plays were produced by Cricot 2.

In 1977, Squat Theatre, a group of young actors who had been exiled from their native Hungary in 1973, performed Pig, Child, Fire!, an experimental play they had originally performed in Budapest in 1975. In Shiraz, the play was staged in a store window on a busy street. One vignette, performed on the sidewalk, depicted the “Slaughter of the Innocents,” the biblical account of the massacre of male infants in Bethlehem by Herod’s soldiers sent to kill the newborn “King of the Jews”. In Shiraz as in Budapest, a soldier wearing a high-collared military overcoat, trousers and boots snatches two babies (plastic dolls) from their mothers’ arms, snaps off their heads and throws them to the ground. A third woman, pregnant and wearing a long, flowery skirt, hurriedly dresses up her young boy to look like a girl, and then seduces the soldier to save her child. The ploy works; the soldier ignores the child, grabs the woman from behind, and the two bend back and forth, fully clothed, in a symbolic gesture of love-making.

The scene was meant to induce repulsion against the tyranny of power; instead, it generated an urban legend according to which a naked actor had raped a naked actress on the street before hundreds of onlookers. Though patently untrue as evidenced by real-time photographs[28] as well as eyewitness accounts by Squat actor and archivist Klara Palotai[29] and theatre critic Iraj Zohari,[30] the tall tale quickly went viral with unfortunate consequences, among them an edict issued on 28 September 1977 by Ayatollah Khomeini, then in exile in Najaf, that urged the [religious] “gentlemen” to “speak out and protest,” for “indecent acts have taken place in Shiraz.” Anthony Parsons, then British Ambassador to Iran also sealed and embellished this misinformation in a book, writing that he was told by an “eyewitness” that a “rape . . . was performed in full (no pretense) by a man (either naked or without trousers, I forget which.”[31] Salacious rumors, especially when propagated from above, tend to nest and rest in the popular mind. Just so, evidence to the contrary, the wretched fiction about the love-making scene in Shiraz continues to circulate even today even among those who were not born in 1977, sadly, even in academia. Slaughter of innocence.

Anna Koos dresses her boy as a girl, Festival Daily Bulletin #4, 1977

Pig, Child, Fire!, Anna Koos and Peter Breznyik, seduction scene. Photos (L): Squat Archives, Budapest, 1975. Photo: (R) Bahman Jalali, Shiraz, 1977.

Western Europe and Latin America

Productions from France included, in 1971, Chroniques coloniales, ou les aventures de Zartan by Jérôme Savary, creator and director, Grand Magic Circus, and in 1977, the world premiere of Honoré de Balzac’s Peines de coeur d’une chatte anglaise, staged by Argentinian Alfredo Arias, Group TSE, a satirical animal story involving Beauty, a magnificent English cat, Puff, an older Persian cat, and Brisquet, a chatty little French cat discussing proper Victorian behavior and other topics of interest in mid-19th century Europe.

Victor Garcia, the Argentine-born director, produced two plays at the festival with the Spanish Teatro Núria Espert, Jean Genet’s Les Bonnes (1970) and Divinas Palabras (1976). In 1974, working with the Ruth Escobar company in Sao Paolo Brazil, he directed Autosacramentales, allegories illustrating the mystery of the Eucharist by Calderon de la Barca, playwright, poet, later Franciscan priest and the foremost dramatist of the Spanish Golden Age in the 17th century.

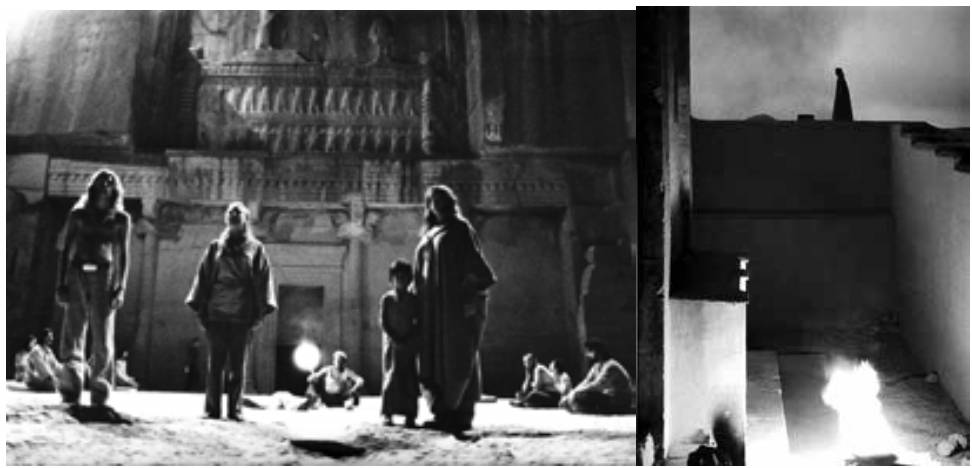

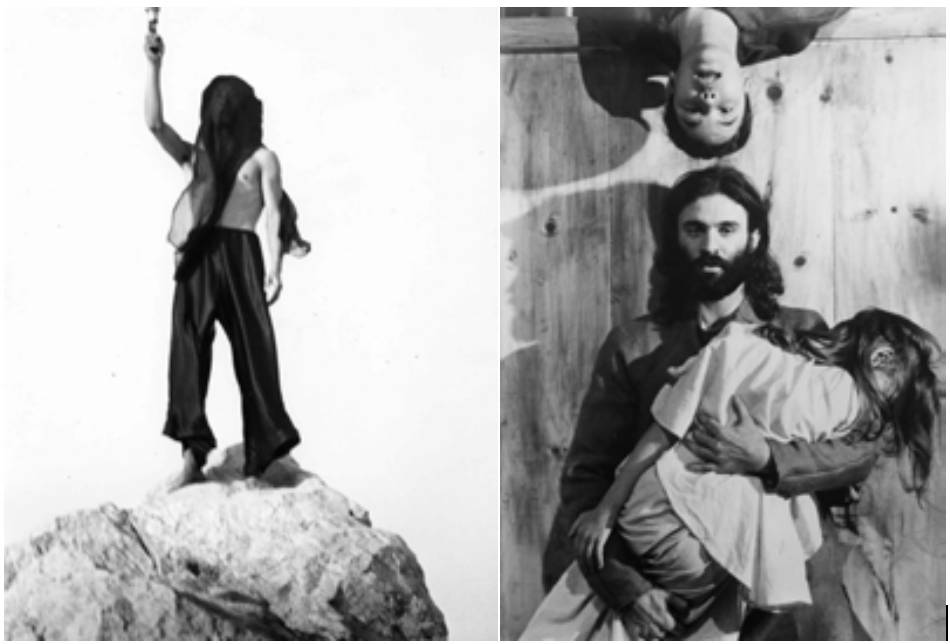

The International Centre for Theatre Research (French acronym, CIRT) founded in 1970 by Peter Brook and Micheline Rozan in Paris was a research center built to explore the cultural, geographic, spatial and linguistic boundaries of theatre.[32] Brook’s visit to Iran in spring 1970 and the screening of his films at the 4th festival in the autumn led to the presentation of CIRT’s first major research project, Orghast, as a “work in progress” at the 1971 festival.[33] Centered on Prometheus, the Greek culture hero who defies the gods and brings fire to man, the two-part work was an experiment led by Brook in Paris with a cast of twenty-five actors of different nationalities, including Iranian, and three collaborating drama directors, Arby Ovanessian (Iran), Geoffrey Reeves (England), and Andrei Serban (Romania). The British poet Ted Hughes and Brook led an improvisatory process in search of a “language” that communicated through sound rather than a linguistic system. Hughes used Avestan and classical Greek vocal elements in the mix and named the invented language Orghast, which became the title of the work.

Orghast I was staged before the tomb of Artaxerxes in Persepolis, and Orghast II, about seven miles further northwest at Naqsh-e Rostam. For Brook, exploring new intuitive possibilities and processes in space, time, language and performance in an ancient landscape and culture was an experience that marked some of his later work, including Conference of the Birds and Mahabharata.

Orghast rehearsal, 1971

Orghast I, Persepolis / Orghast II, Naqsh-e Rostam

Japan

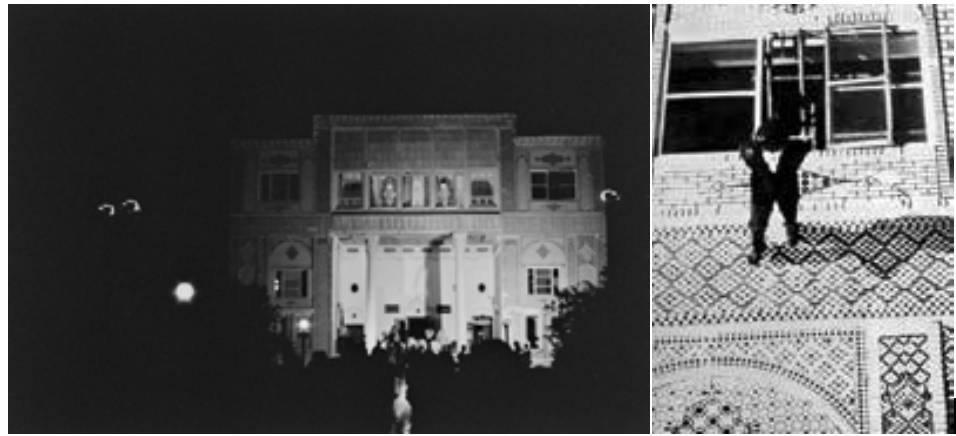

Two extraordinary works were presented from Japan, both by Shuji Terayama, an iconoclastic, provocative, prolific and extremely inventive avant-garde artist who worked in different mediums— poetry, film, photography, and “meta-theatre.” Terayama staged his Origin of Blood in Delgosha Garden (1973), and Ship of Folly at Saray-e Moshir (1976). The performances combined qualities of shamanic dreams and nightmares, magic, madness and lucidity, and the occasional suspension of belief as in Origin of Blood, where an actor descended from the top of the Delgosha Pavilion down to the garden, walking vertically, face-down, seemingly without any device to save him from the pull of gravity, only his will.

The effect of the illusion was shocking and beautiful.

Origin of Blood, descent from the façade of the Delgosha Pavilion, 1973. Photos: Jean-François Camp

The Ship of Folly program, 1976. Design: Qobad Shiva and Fowzi Tehrani

U.S.A.

The festival presented a variety of American off-Broadway productions both by recognized practitioners of experimental theatre and others that were on the fringe and grew to become iconic in the 1970s following their performances at the festival. One great source of attraction for all dramatists at the festival was that they were free to choose their preferred venue, as available and feasible.

In 1970, Peter Schumann, founder and director of Bread & Puppet Theatre, was the first to introduce festival audiences to experimental American theatre with Fire and King’s Story. Before each performance an actor read a statement of protest against political oppression then another actor distributed freshly baked bread among the audience, which fit well with “theatre and ritual,” the main theme of the 4th festival, and the play was performed with the company’s trademark giant puppets. Schumann also decided to perform in a park and outside a prison, free of charge.

Bread & Puppet, Fire, and free show in the park, 1970

Three more plays in the experimental category were performed in 1971. Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theatre performed two ground-breaking collective “works in progress,” Terminal and Mutations, both in the university gymnasium. Andre Gregory chose a fruit warehouse for his production of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, a program of the Manhattan Project. While meticulously designed, the performance was in the style of an on-the-spot improvisation and found an exuberant audience, some of them children perched on a treetop, which seen from “Alice’s” perspective— American actor Angela Pietropinto—looked like “a tree that was growing children!”

Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carrol, children crowding treetops and Alice, 1971. Photos: Courtesy of Angela Pietropinto

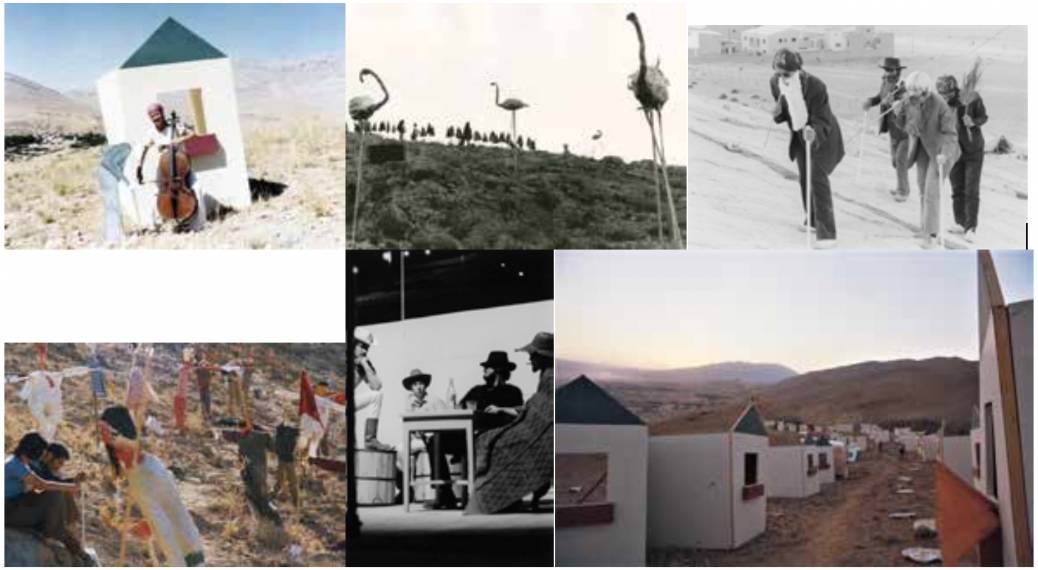

The most singular experimental work in the 6th festival in 1972 was KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE, staged by then-little-known Bob Wilson and his Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, with a mixed American-Iranian cast of live and cardboard cut-out characters totaling nearly 550 in the festival program catalogue.

Staged like a simple children’s play with no sophisticated lighting or technical support, the play was preceded by an Overture staged at Qavam House, an elegant 19th century residence in Narenjestan Garden where the audience happened across various members of a “family” posing scenes of daily life in extreme slow motion. There was no apparent storyline and the scenes, set in separate quarters, seemed unconnected. KA MOUNTAIN began the next day on a platform set up as a stage at the bottom of Haft-Tan, a hill named after seven Sufis who are buried in a nearby garden. The audience was free to follow the family here and there up the hill nonstop for 168 hours for an entire week and follow disparate scenes, also in extreme slow motion, dotted with fish, animals, birds—some real, others not, as if retreating to an earlier geological era—as Moby Dick was being read out on the platform below. On day seven, the play ended on top of the hill next to a giant cardboard dinosaur with people chanting the “Dying Dinosaur Soars.”

Juxtaposing real and surreal visual elements and slowing down time to the extreme led to a heightened awareness and meditative experience that, without a connecting narrative was, by definition, different for each spectator. And yet there was a unifying undercurrent, a quest and a progression toward an end, as if to evoke Attar’s Conference of the Birds where seekers travel across seven valleys to reach the final station atop Qaf Mountain.

KA MOUNTAIN happened because of the trust that the festival put into Bob Wilson’s creative impulses on the one hand and his willingness to believe in impossible things on the other.[34] The American actors and the Iranian participants—not everyone an actor—had in the director’s absence rehearsed fragmented scenes in Shiraz and built some props expecting the parts to come together as a whole later. Bob Wilson arrived in town at the 11th hour and framed the elements on the spot and situated them on the hill. The entire process was a daily improvisation and discovery for the creator himself, the actors, and the spectators. Nothing like it had ever been conceived in the history of theatre or attempted before. The mythic theatre that was born in Shiraz lives on and takes different shapes in the imagination even today.[35]

Bob Wilson, 1972

KA MOUNTAIN, Haft-Tan, 1972. Photos: Jean-François Camp

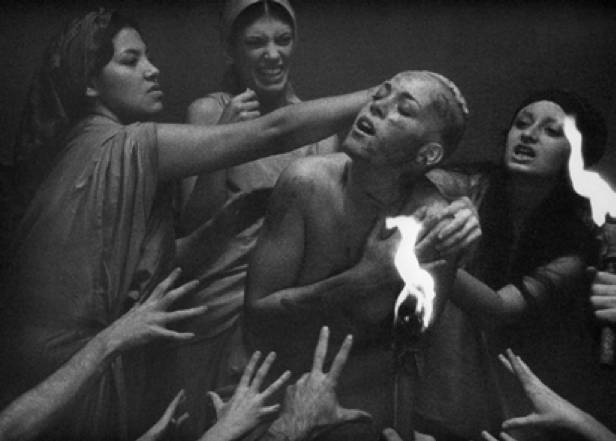

Bob Wilson returned to Shiraz in 1974 where he staged A Mad Man, A Mad Giant, A Mad Dog, A Mad Urge, A Mad Face in the Delgosha Pavilion, a play created collaboratively with Christopher Knowles. Andrei Serban produced Fragments of a Greek Trilogy: Medea, Electra, Trojan Women, with New York’s La MaMa at Persepolis in 1975, a powerful production that was rooted in his experience as a collaborator on Orghast. In 1977, he returned with Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy, As You Like It, a memorable La MaMa production that turned out to be the last U.S.A. experimental theatre at the festival. The audience merrily followed the actors across Delgosha Garden to hear the melancholy Jacques pronounce “All the world’s a stage,” the famous quote that gave birth to the phrase “too much of a good thing.”

Medea / Electra

Trojan Women Photos of Fragments of a Greek Trilogy, 1975, courtesy of Andrei Serban

Film

Film program, 1969. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

Starting in the inaugural year in 1967, the festival screened films on a daily basis to packed audiences, most of them youth, initially at Paramount and Capri cinemas, and from the third year, at Ariana, a newly-built and well-equipped theatre owned and operated by the filmmaker and Shiraz native, Shahrokh Golestan. The programs covered international masterpieces on the one hand—including retrospectives of Brook (1970), Bergman (1971), Buñuel (1974) and Satyajit Ray (1971) —and contemporary films by the likes of Joseph Losey, Tony Richardson, Ken Russell, Istvan Szabo and movies by the new generation of Iranian filmmakers.

Retrospectives: Ingmar Bergman, Satyajit Ray, 1971; Luis Buñuel, 1974. Poster design: Qobad Shiva

The first movie screened at the inaugural festival in 1967 was writer- director Fereydoun Rahnema’s Siyavash in Persepolis, a cinematic experiment with mythic characters from the Shahnameh wandering about the ruins of Persepolis and reflecting on the past and the present; the film had won the Jean Epstein Prize at the 1966 Locarno Festival for its innovative exploration of film language.

Siavash at Persepolis, 1965

The festival organized an unusual and important program in 1970 when the theme was “theatre and ritual,” during which Jean Rouch, the French filmmaker considered a pioneer of visual anthropology, screened uncut footage of African rituals, among them, Dogon tribal ceremonies in Mali.

The programs that were organized around themes included, in 1975, musicals from the Golden Age of Hollywood and beyond, and in 1977, “Japan: History through Cinema,” which included masterpieces by Ichikawa, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Oshima, and Ozu.[36]

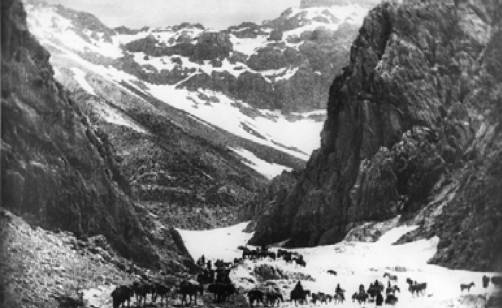

On the 10th anniversary of the festival in 1976, the theme of the film program was “the East as seen by filmmakers,” ranging from silent movies to sound. The program included Grass by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack (1925), a silent documentary—one of the earliest of its kind—that follows the seasonal migration of a Bakhtiari tribe and their livestock across the Karoun River and snow-capped Zard Kuh in southwestern Iran, and Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Heir to Genghis Khan (also called Storm over Asia) (1928), The Yellow Cruise (1935), a documentary on China co-directed by Léon Poirier and Andre Sauvage, and Azalea Mountain, a Chinese model opera made into film (1974).

Grass, 1925

Films on India included Jean Renoir’s, River (1951), Roberto Rossellini’s documentary drama, India (1958), and India Song by Marguerite Duras (1975).

The River, 1951

India, 1958 / India Song, 1975

The “East” theme also included Sergei Parajanov’s masterpiece, The Color of Pomegranates (1968) (Sayat Nova, original title) that had been removed from circulation in the Soviet Union and was first shown at the festival in Shiraz; Giorgi Shengelaya’s Pirosmani (1969), Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (1973), Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1001 Nights (1974), Shuji Terayama’s Throw Away your Books (1971) and Pastoral Hide and Seek (1974), Shadi Abdel Salam’s, The Mummy (1969), Pharaoh by Jerzy Kawalerowicz (1966), and Jamil Dehlavi’s Towers of Silence (1975).

1001 Nights, 1974 / Pastoral Hide and Seek, 1974

Iranian filmmakers in this category included Fereydoun Rahnema with his Pesar-e Iran az Madarash Bikhabar Ast (Iran’s Son has no News of his Mother) (1973). A number of banned Iranian movies were screened at the festival: two groundbreaking works by Dariush Mehrjoui, Gav (Cow, 1969) and Dayere-ye Mina (The Cycle) (1975); and Nasser Taqva’i’s Aramesh dar Hozour-e Digaran (Tranquility in the Presence of Others) (1970).

Gav, 1969

Aramesh dar Hozour-e Digaran, 1970

The new generation of Iranian filmmakers whose films— feature-length, documentary or short— were screened at the festival included, to name a few, Mehrjoui, Aqay-e Halou (Mr. Gullible, screened in 1970) and Postchi (The Postman, 1972); Arby Ovanessian, Cheshmeh (The Spring) (1971), Parviz Kimiavi’s feature films, Mogholha (Mongols) (1973) and Bagh-e Sangui (Stoney Garden) (1976), and documentaries, Ya Zamen-e Ahou (Oh, Protector of Gazelles) (1970) and P Like Pelican (1973); Sohrab Shahid-Saless, Tabi’at-e Bi-jan (Still Life) (1974), and Dar Ghorbat (In Exile) (1975).

Cheshmeh, 1971 / Mogholha, 1972

Postchi, 1972 / Tabi’at-e Bi-jan, 1974

Other documentary filmmakers who participated in the festival were Ahmad Faroughi, Telephone (1966) and Parsiyan-e Hend (The Parsees of India) (1970); Jalal Moghaddam, Mashhad (1967); Taqva’i, Bad-e Jenn (1969), Zohr-e Ashura (1971), and Sadeq Kordeh (Sadeq, the Kurd) (1972), a feature-length film based on an historical event.

Daryereh-ye Mina, 1975 / Bagh-e Sangui, 1976

Iranian shorts included Khosrow Sina’i, An Su-ye Hayahou (Beyond Pandemonium) (1968); Taqva’i, Mashhad-e Qali and Arba’in (both screened in 1969); and Shokoufeh Shakeri, Sarab (Mirage) (1971); Nasib Nassibi, Che Harasi Darad Zolmat-e Rouh (The Fearful Darkness of the Soul) (1972) and Zendegi (Life) (1969), an animation by Nosrat Karimi.

Bad-e Jenn, 1969

The festival itself was the subject of several documentaries namely, Jalal Moghaddam, Shiraz va Jashn-e Honar (1967), Mahmoud Khosrowshahi and Tony Williams, Sound the Trumpets, Beat the Drums (1968), François Reichenbach, Festival dans le desert (1969), Kimiavi, Jashn-e Honar-e 49 (1970) and Taqva’i, The Fifth Festival of Arts (1971).

The 12th Festival

The 12th Festival of Arts was scheduled to open on 3 September 1978 at the end of Ramadan. By then the country, suffering from a severe economic malaise that was induced and increasingly fueled by the politics of oil, was in the grip of a popular uprising that was to culminate in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. In the summer of 1978 people were on the streets, tensions were high, government workers were on strike, massive demonstrations were organized by a coalition of activists from the left, right and center marching under the banner of religion, which engineered and unified the otherwise pluralistic and initially secular protest movement by billing itself as a democratic liberating force. On August 19, religious zealots set the Cinema Rex in the southern city of Abadan on fire, burning more than four hundred innocent moviegoers to death. The momentum was unstoppable. Given the turbulent and threatening conditions, the festival organizers decided to cancel the 12th Jashn-e Honar.

The performing arts were not new to Iran and had been cultivated, practiced and promoted by public and private institutions in the country for more than a century. Native and foreign forms of music, theatre, dance, and film were part and parcel of public life in Iran and were tolerated even by religious doctrinaires that considered most artistic activity sacrilegious profanity, especially where women were involved. The difference during 1967-1977 was that ten out of 356 days a year the Shiraz Festival of Arts distilled and unleashed the full power of creativity free of any political agendas or directives and not from a third world perspective but as an equal partner with the rest of humanity in the 20th century. As such, it stood out, eliciting admiration and accolades, but also a level of criticism and hostility beyond the standard share accorded all groundbreaking, high visibility cultural events around the world.

Interrupting the flow of the festival was “like tearing a page out of an unread book.” But memories linger, experiences are handed down, and historic paradigms are recalled and activated. The knowledge that it was possible to build and exercise a free, tolerant, creative, and diverse society in Iran—which is what the festival was all about—and the footprint of the cultural awakening that it elicited cannot be erased. The last chapter of Jashn-e Honar is yet to be written.

This paper was originally commissioned by Asia Society for The Shiraz Festival: A Global Vision Revisited, a symposium held in New York on 5 October 2013. It has been expanded considerably for this publication.

The sources in print consulted for this report are Festival catalogues, bulletins, program notes, 1967-1977, Tamasha magazine, 1971-1977, Kayhan, Ettela’at, and their companion English editions, Kayhan International and Tehran Journal, 1967-1977; interviews with Farrokh Gaffary (1984) and Bijan Saffari (1983), Foundation for Iranian Studies, “Program for Oral History,” and Sheherazade Afshar Ghotbi, Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of Arts (1967-1977): Detailed catalogue of events, January 2018 (available online). First-hand accounts of the festival were contributed by Reza Ghotbi, Sheherazade Afshar and Arby Ovanessian; Parviz Sayyad and Mohamad-Baqer Ghaffari provided input on ta’zieh. All omissions and editorialized commentary in this report are the sole responsibility of the author.

[1]Enrico Fulchignoni, professor and director of UNESCO’s International Committee for Cinema and Television, first published in Il Tempo at the close of the 9th festival in 1975, translated in Tamasha 246 (1976): 74.

[2]Chapter headings in Mahlouji’s Archaeology of the Final Decade: The Utopian Stage, Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis (1967-77), a brochure available online that accompanied his exhibitions of the festival in Paris, Rome, London, Bergen, and Liverpool during 2014-2016.

[3]Pazhuheshi Zharf o Setorg o No dar Sangvareha-ye Dowre-ye Bistopanjom-e Zaminshenasi, lit., “A Profound, Prodigious and Novel Research into the Fossils of the 25th Geological Era.”

[4]Co-commissioned with the French Ministry of Culture.

[5]Launched in March 1967, NITV merged with Radio Iran in 1971 and was renamed NIRT.

[6]Excerpts from an address by Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi at the inaugural festival. Festival catalogue 1967.

[7]Ibid.

[8]The festival’s principal programs were music, theatre, dance, and film (described separately below under “Programs”), seminars and conferences, daily round-table discussions and debates, and related publications. Poetry and painting, exhibitions of Persian carpets and handicrafts, children’s theatre and dance workshops and other special programs intermittently organized by the festival are not covered in this report.

[9]Khosrovani was only involved with the festival in 1967 but his lighting design for Hafezieh and Persepolis endured and defined the tone, ambience, and the accents of the outdoor venues for the next ten years through 1977.

[10]Photo credits have been provided in this report as available.

[11]The following is a partial list of other Iranian musicians, older and younger, who appeared at the festival: Fereydoun Hafezi, Ata’ollah Jangouk, Habibollah Salehi, Reza Vohdani, Houshang Zarif, and Nasrollah Zarrinpanjeh (tar); Nosratollah Ebrahimi and Jalal Zolfonoun (setar); Mohammad Heydari, Pashang Kamkar, Parviz Meshkatian, Majid Najahi, Mansour Saremi, Ebrahim Sarkhosh, Reza Shafi’ian, Fazlollah Tavakkol, Reza Varzandeh, Abbas Zandi (santour); Mohammad-Ali Haddadian, Mohammad Moussavi, Hassan Nahid, Mohammad-Ali Kiani-Nejad (ney); Maliheh Sa`idi (qanoun); Mehdi Azarsina, Davoud Ganje’i, Mohammad Moqadassi, Mahmoud Rahmanipour, Ali-Akbar Shekarchi, Siavosh Zendegani (kamancheh); Rahmatollah Badi’i (qeychak); Amir-Nasser Eftetah, Mohammad Esma’ili, Mohammad Farahmand, Nasser Farhangfar, Hossein Hamedanian, Morteza Haj-Ali A’yan, Arjang Kamkar, Bahman Rajabi (tombak); and singers, Ahdieh Badi’i, and Simin Ghanem, Iraj, Noushin Riahi, Parivash Sotoudeh, and Sowgol.

[12]Gorouh-e Jam’avari va Pazhuhesh-e Musiqi-ye Navahi.

[13]Financial Times, 9 October 1968.

[14]Renamed NIRT Chamber Orchestra in 1967 (following NITV’s merger with Radio Iran).

[15]Robert J. Gluck, “The Shiraz Festival: Avant-Garde Arts Performance in 1970s Iran,” Department of Music, University at Albany (2006): 217.

[16]All works commissioned by the NITV/NIRT Music Department.

[17]Terry Graham, Tamasha 8 (September 1972).

[18]Gluck, “The Shiraz Festival,” 217, 221, citing 25 December 2005 email correspondence with Carolyn Brown.

[19]In 1973, Iran was host to the 2nd Third World Theatre, a festival and conference held in Shiraz that was supported by the 7th festival on the organizational, though not on the programmatic level.

[20]For more information on Iranian plays mentioned in this report, see The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Asia Pacific, ed. Don Rubin, et al (London & New York: Routledge, 2001), 201-218.

[21]Ibid., 208.

[22]The title, Haza Habibullah, Mata fi Hubbullah, Qatilullah, Mata Beseifullah (All at Once Friend of God, Died in the Love of God, Slain by God, Died by the Sword of God), derives from Tazkarat al-Awlia by Fariduddin ‘Attar (d. 1221), a work in Persian prose on the life of Sufis.

[23]It is a paradoxical and tragic irony that in 1989, Nalbandian, unemployed and impoverished following his release from prison by the IRI for his role in the Theatre Workshop, committed suicide. On 5 October 2013, speaking about the essence and the trajectory of the Shiraz Arts Festival at the Asia Society Symposium in New York, Ovanessian closed his remarks with a reference to Nalbandian’s Nagahan…, the implication being that the festival was a voice of exploration, creativity and knowledge that was silenced not only by the 1979 Islamic Revolution but by the community of critics that have declined to write about the festival since.

[24]For the history and development of theatre in Iran, and a discussion of the numerous plays performed at the Shiraz Arts Festival not mentioned here, see The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre, Asia Pacific: 204 ff.

[25]Gisèle Kapuscinski, Ph.D. Dissertation, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University, 1982.

[26]Savari Dar-amad Ruyash Sorkh, Muyash Sorkh. . . “There Appeared a Knight with a Red Face, Red Hair, Red Lips, Red Teeth, a Red Gown, a Red Horse, a Red Spear…”

[27]All participants contributed to content development: Ovanessian, director, Fozieh Majd, music, Ferdows Kaviani, Sussan Taslimi, Sadreddin Zahed, and the young boy Nima Mofid (actors).

29 Photojournalist Bahman Jalali’s image taken onsite in Shiraz (Alireza Rezai, “In Search of a Historical Battle,” Festival Daily Bulletin #4, 20 August 1977) shows the woman and the soldier in the outfits they wore throughout the play. A Squat archival image shows the soldier wore the same outfit in the play’s inaugural 1975 Budapest production and subsequently.

[29]Klara Palotai, New York-based digital archivist of Squat Theatre and a member of the group both in Budapest and Shiraz, has attested by email to this writer that both actors remained fully clothed, in Shiraz as in the original performance.

[30]Iraj Zohari describes the scene in his Yad-ha va Boud-ha: Khaterat-e Iraj Zohari. Mo’in (Tehran, 1382): 211, and refuting the rumors, scoffs at the Shirazi religious leaders for their uproar over what was a “symbolic gesture in a play.” This writer also attended the performance; I likewise verify that both actors remained fully clothed for the entire length of the play.

[31] صحیفه امام، مرکز نشر آثار حضرت امام خمینی (ره)، جلد سوم، ص ۲۲۹-۲۳۱ (Center for Publishing Imam Khomeini’s Works, v. 3: 229-231, cites Khomeini’s edict along with a Persian translation of a passage in Anthony Parsons’ The Pride and the Fall: Iran 1974-1979 (London, 1984).

[32]In 1974, CIRT was renamed Centre International de Créations Théâtrales (CICT) to include theatre production.

[33]For a detailed discussion of Orghast, see Negin Djavaherian, Not Nothingness: Peter Brook’s Empty Space and Its Architecture, Ph.D. dissertation. School of Architecture, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, August 2010, available online.

[34]For Wilson’s perspective on this subject see Iran Modern (New Haven & London: Asia Society Museum, 2013), exhibition catalogue, 93.

[35]See https://vimeo. com/46089267, a 2012 video in which Bob Wilson outlines the seven-day progression of the play and ends with him chanting the dinosaur song. In his retelling, he describes Haft-Tan (Seven Bodies) as constituting seven hills; in fact, the play unfolded in seven stages on one hill.

[36]Other Japanese filmmakers represented were Yoshimura, Shinoda, Inagaki, Kuroki, Yamamura, Yoshida, Naruse, Kobayashi, Shindo, Okamoto, and Kinoshita.