Radio: A New Cultural History of Listening to Iranian Music, 1940-1952

Radio: A New Cultural History of Listening to Iranian Music (1940-1952)[1]

Pouya Nekouei

Introduction

Radio was a significant medium in the formation of modernity’s global soundscape. From the early decades of the twentieth century, radio became an important part of mass media, not only in Western capitalist contexts, but in the Global South as well. The sonic milieu created by radio significantly transformed the ways people listened to sound and music and received data. Radio, as Meltem Ahiska points out, was “a public political instrument” through which the state and the ruling classes promoted nation building, spread political propaganda, and fostered cultures of consumption.[2] In Iran too, radio’s foundation was a tool invested in by the state, but it was also a turning point in the history of sound, listening, and music.

In this article, I focus on a contested theme in the historiography of music in radio, make a few revisions to the current literature, and present new documents on the subject: the case of Iranian music performed in and broadcasted from Radio Tehran, since its establishment in April 1940 until early 1950s, which is concomitant with the political turmoil of the oil nationalization movement in Iran. While radio’s role in the promotion of popular music is an accepted assumption, the role of Iranian music in this medium remains a point of contestation among writers. In this article, I argue that Iranian music, including Iranian art/ classical music,[3] was crucial to radio’s programming throughout this roughly twelve-year period. In other words, despite all the administrative changes in radio, Iranian music was continuously listened to by the audience of radio during this period.

The radio’s emergence was indeed a unique phenomenon in the performance history of Iranian music. The radio studio was a unique space, given the live nature of performances during this period.[4] Narratives left for us testify to perplexities of musicians and odd instances during live performance sessions. Tales of technological malfunctions, or musicians’ errors during live performances provide a glimpse into this unique experience of live performances. Javad Badeezadeh (1903–1980) recounts that in the early days of radio, he and his accompanying ensemble, including Saba, Somaei, Neydavud and Tehrani were performing in a live radio session, throughout which the studio’s light had to be switched off, due to the perils of the Second World War.[5] According to his narrative, the ensemble finished the opening sections, but Badeezadeh could not find the lyrics of the song. The notebook containing the lyrics fell on the ground, and after the orchestra had performed twice, Badeezadeh, ridden with anxiety, improvised an alternative lyric for the song that later angered the lyricist, Nurollah Homayun.[6]

However, an important aspect was that radio enabled mass accessibility to the listening experience of Iranian music for modern listening subjects. ence, radio led to a wider listening experience of Iranian music than was earlier ushered in by the gramophone, mainly during the Reza Shah period. This wider sociability of Iranian music and its listening experience had interesting gender dimensions, too: radio made the voice of female vocal musicians performing āvāz and taṣnīf available to the wider public.[7] More importantly, radio subjected the performance of Iranian music to the new discipline of time; musicians in radio had to perform in specific time schedules and hours; this meant that each performance session was distinct, and different genres of music, including Iranian art/classical music, had space in this mass media.

Problems of Writing the History of Music in Radio

Writing the history of music in radio in modern Iran is not an easy task, and involves various historical, as well as conceptual challenges for at least two reasons: (a) with respect to the period of the present study, access to primary sources has been a major obstacle; (b) the second issue concerning music history of radio is a complex historiographical problem regarding musical life in radio during the Pahlavi period. Writers and music activists generally associated with the revivalist music movement have constructed a narrative of music history informed by a revivalist discourse.[8] In this narrative, the music broadcast from Radio Tehran is generally considered as the Other of Iranian art/ classical music and therefore tantamount to being ‘inauthentic’. The ‘authentic’ age of Iranian music, according to music revivalists, was the late Qajar era of music, and the music broadcast from radio represented ‘light’ and ‘non-serious’ music. This situation has largely to do with the ideological issues apropos of the historical narrative of Iranian music, specifically the one broadcasted from Radio Tehran prior to the 1979 Revolution. Musicians of the Gulhā program— broadcast on the radio from the mid-1950s on— represented the mainstream musical current of Iranian music prior to the 1979 Revolution.[9] As a result of the emergence of the revivalist music movement in the 1960s, and a gradual shift in musical discourse and practice, musicians associated with the Gulhā program were marginalized in post-revolutionary musical discourse. The 1979 Revolution ousted these musicians from public musical life in post-revolutionary Iran. riticisms of Iranian music broadcast from radio within the revivalist discourse began with the activities of Nur-Ali Borumand in the 1960s and continued in the years to come. Borumand, as a major revivalist figure, criticized what he considered to be “false improvisation.”[10] The music broadcast from Radio Tehran in the revivalist narrative was considered to be the symbol of such designation, and Iranian music broadcast from radio was increasingly and derogatorily referred to under such rubrics as mūsīqī-i rādiyūī (radio music) or shīrīn navāzī (sweet performance).[11] It was Majid Kiani, a major figure in revivalist music discourse, who employed the term shīrīn navāzī, thus associating ‘lightness’ and a sense of ‘amusement’ with a major part of Iranian music broadcast from radio.[12] I argue that these monolithic binary metanarratives of music history vis-à-vis radio have rendered an entire thirty-seven years of music history of Iranian music in radio to an ideologically reductionist ahistorical narrative, overlooking detailed historical and stylistic examinations of music in radio.

In recent years, there has been a growth in historical and conceptual studies of radio in modern Iran. Sasan Fatemi, in his work on the emergence and development of popular music in Iran, suggests the foundation of radio “symbolically” is “the starting point for the definite formation of popular music” in Iran.[13] He also believes that the process of commercialization of music was accelerated with the establishment of radio in Iran.[14] In his work, the binary of ‘popular,’ versus ‘classical’ has been central to the binary narrative of contemporary music history generally, and specifically that of radio’s during the Pahlavi period.[15] In this study, I distance myself from conceptualization of radio as a promoter of commercial music, and borrow from the cultural history of music. Historicization of sound and listening over the past few years has become a major focus of cultural historians of music.[16] Of course, radio did not necessarily lead “disciplined listening” practices, as cultural historians of music have argued vis-à-vis musical life in public and private spaces, but it is clear that the broadcasting of Iranian music on radio led to an unprecedent sociability of this music at a large scale notwithstanding the varied tastes, cultural, or religious orientations of the listening subjects.

Another major work on the history of radio in Iran belongs to Mohammadreza Fayyaz. Fayyaz, in his historical analysis, provides a detailed narrative of the initial years of radio, and contextualizes radio in the larger socio-political context, cultural politics, and discourse of Reza Shah’s period. Fayyaz acknowledges the role of Iranian music in this media, and analyzes a series of issues surrounding musical politics and factional contestations between music groups in radio until the mid-1940s.[17] He challenges the normative narrative of early radio’s music history—that is, of music on radio since its foundation, and until Reza Shah’s resignation—in which Qolamhoseyn Minbashian’s opposition to Iranian music has been a central theme and a matter of debate.[18]According to Fayyaz, only a few selected virtuosic musician could enter the space of radio, given the high musical standards expected by Minbashian as head of the radio’s music programs.[19] He then points to various issues pertaining to music on radio after Vaziri’s take over, following Reza Shah’s resignation from power, including the contestations between Vaziri and his colleagues, and an emerging support of pro-western music led by Parviz Mahmud until the mid-1940s.[20] While by and large I agree with his narrative, I stress on the performance of Iranian vocal and solo instrumental music, and smaller ensembles, until roughly early 1952, in time-bounded schedules. Despite all of the administrative problems in radio, this continuity in the performance of Iranian music until the early 1950s led to the wider listening of it by a larger public. This was an important aspect, specifically in the history of Iranian art/classical music, for while traditionally Iranian art/classical music was bound to a tiny segment of music lovers from among Qajar elites in the latter half of the nineteenth century, radio ironically, as a mass media, accommodated Iranian music, including the Iranian art/classical, during this period. Hence, Iranian art/classical music, including instrumental forms such as pīshdarāmad, and ring, and vocal music—that is, āvāz and taṣnīf—were performed in radio during this period and were appreciated by a wide range of audiences.

Radio Goes Public in Modern Iran

Radio became a contested device and medium in the cultural and political discourse in Iran soon after its establishment in 1940, capturing the attention of policy makers and the public alike. Devices became an attractive object in the market from the late Reza Shah period, and immediately after the foundation of Radio Tehran, they were advertised in newspapers, and circulated in the market.

An Advertisement for a brand of radio. Iṭilā‘āt, April 23, 1940. (Figure 1.)

An Advertisement for a brand of radio. Iṭilā‘āt, April 23, 1940. (Figure 1.)

Advertisement for Philips Radio. Source: Tehran Muṣṣvar, 1947. (Figure 2.)

Advertisement for Lafayette Radio. Source: Tehran Muṣṣvar. 1950. (Figure 3.)

Radio was pivotal to the state’s policies and the dissemination of its political agenda. Fayyaz outlines how this medium was situated in the late Reza Shah’s modernizing discourse of the ‘cultivation of thought’ or parvarish-i afkār.[21] The daily Iṭilā‘āt referred to radio’s founding as “a significant educational institution, whose reach is as far as the globe.” This advertisement also promised that it would make available “the pleasant music of esteemed musicians of the country to people’s ears.”[22] As early as the 1940s, policymakers were intrigued by radio’s wide outreach in Iran and beyond. A report addressed to the minister of finance and the chief of radio’s commission in the first months of radio’s foundation submitted that, from June 1940, the sound of Radio Tehran was audible throughout the country, and its range extended as far as Kabul, Baghdad, and Berlin.[23] Soon the sound of Radio Tehran became audible in a transnational sound space, and Persian-language broadcasting became part of global media production.

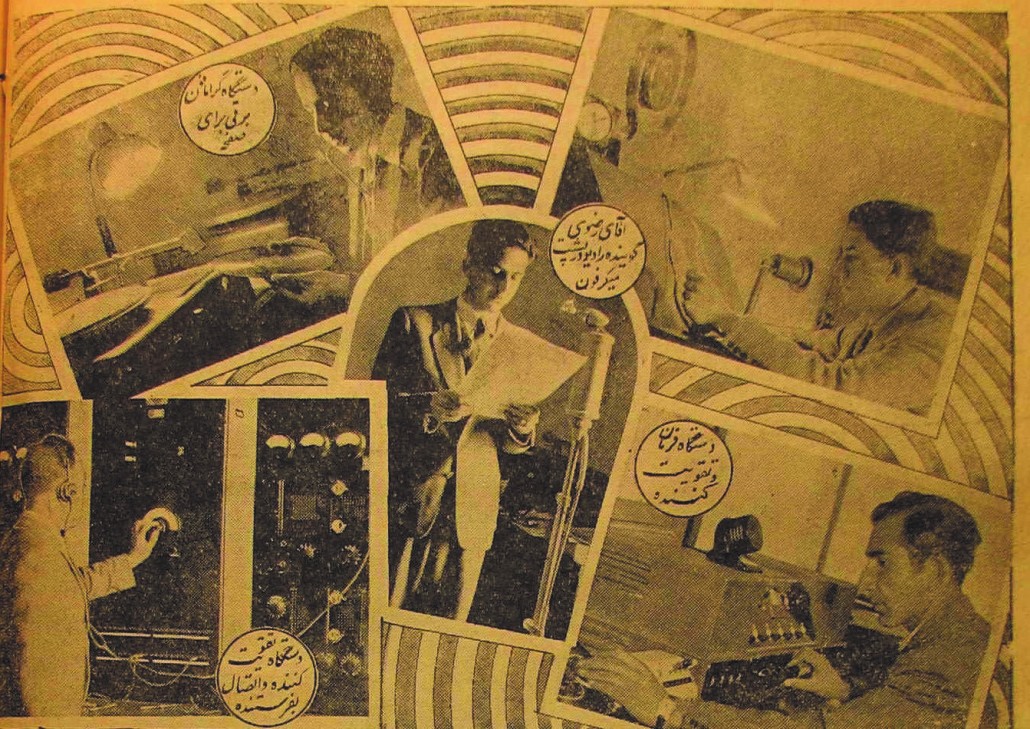

Studio and equipment, Radio Tehran Iṭilā‘āt-i Haftegi. (Figure 4.)

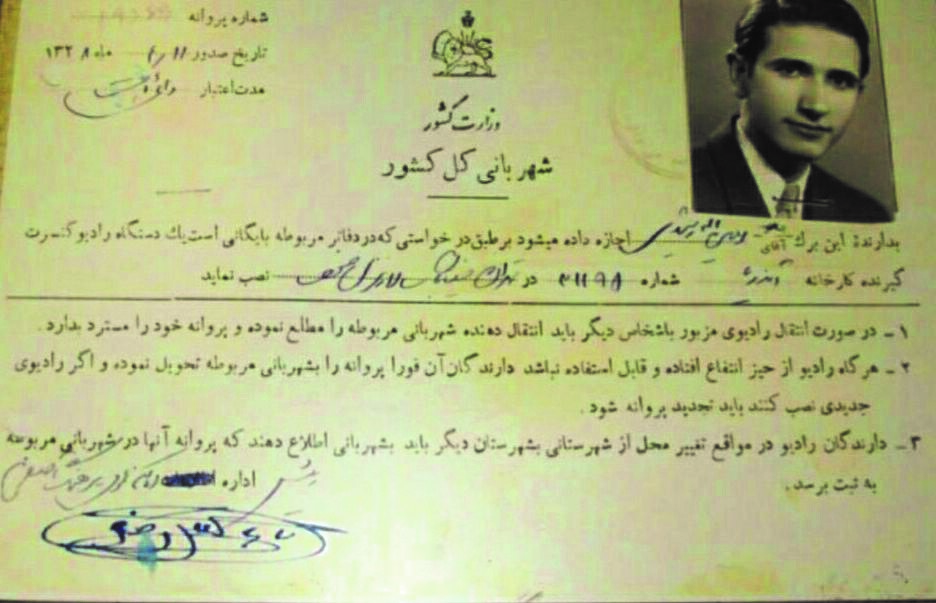

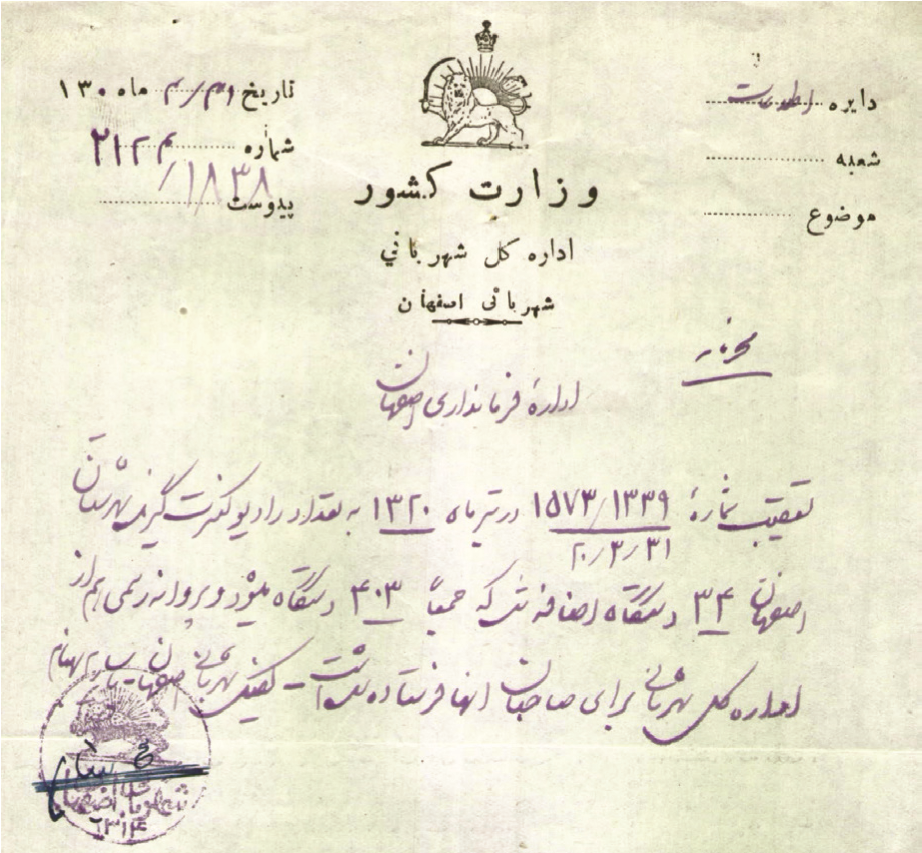

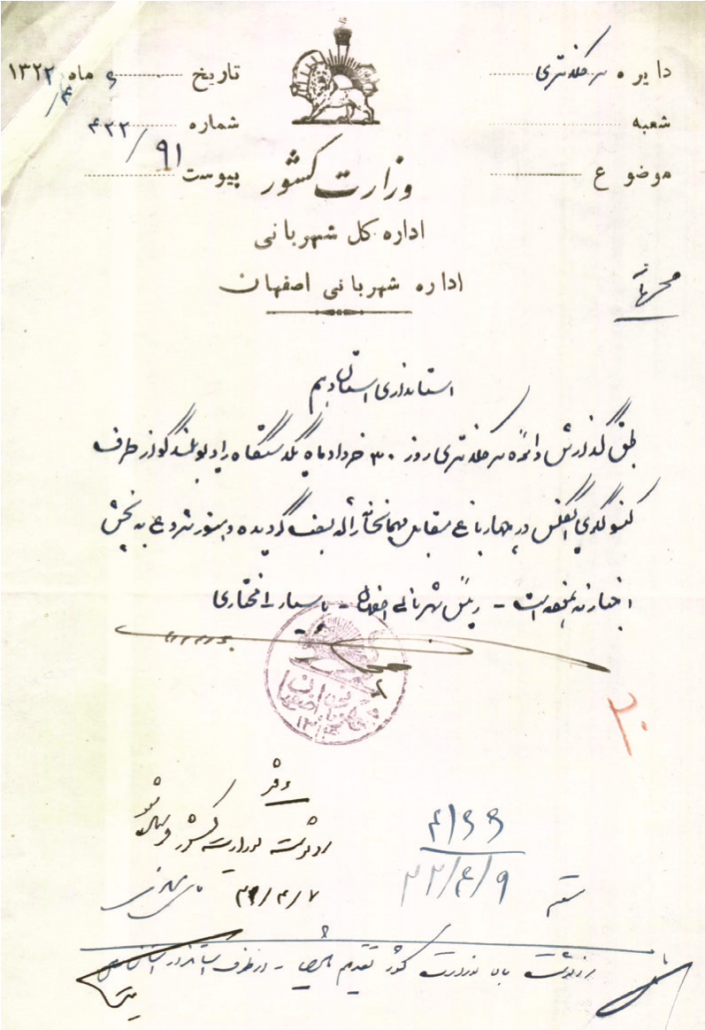

Like the gramophone, radio became an object of political and administrative intervention as well as state control in Iran. itizens, from the late Reza Shah’s reign and also in the tumultuous context of World War II, were required to have specific permissions issued by officials in order to own a radio device. Such policies were clearly aimed at controlling the flow of information through a sound device that had no precedence in terms of circulation. A document issued by the General Directorate of Police of Isfahan in June 1941 mentions that an additional thirty-four radio receivers are added, totaling 403 receivers in the province of Isfahan (Figure 3). The same document mentions that the official permission is sent by the police bureau to the owners. In 1943, another document informs the authorities that in June 1943 a radio speaker was installed in Isfahan’s Chaharbagh street in order to broadcast news. During World War II, the radio was also used by foreign forces in Iran. Apparently, these programs were a matter of contestation. An advertisement in the weekly Iṭilā‘āt states that based on a directive sent by the general directorate of the propaganda bureau, all programs of the allied forces on the radio, including programs of the British and Indian army, the Soviet cultural house, the program for the Polish population, and the educational English language program, will come to a standstill.[24] Radio was also used as a disciplinary apparatus; an example of this was a radio station in the 1940s owned by the police, whose main objective was to make the prisoners’ narrative audible in order to prevent crimes, but also to announce its investigative operations of criminals, and to seek public help.[25]

Official permission granted to singer, Aminollah Rashidi, to own a radio device. Early 1940s. (Figure 5.)

Source: National Library and Archives of Iran. (Figure 6.)

Source: National Library and Archives of Iran. (Figure 7.)

Despite such issues, music from the heyday of radio became a crucial part of broadcasting programs. As early as the founding of Radio Tehran, the authorities attempted to incorporate different genres of music in its programming. An order issued from the prime minister’s office requested the ministry of foreign affairs to oversee the purchase of a significant chunk of gramophone records from Norway, for broadcast from Radio Tehran. Soon after, in June 1941, the military college’s orchestra began to perform on Radio Tehran.[26] Musicians performing Iranian music appeared in the radio’s studio from very early on. The audience was not only able to listen to voices of prolific vocal musicians of Iranian art/classical music, and instrumentalists performing musical instruments such as the ney, tar and santur, but also experienced the opportunity to listen to newly composed songs and a few orchestras and ensembles with instruments such as piano and violin.

The wide outreach of the radio’s sound and musical production was significant and indeed a sensitive issue, considering the religious sensitivities of sections of the public. Broadcasting authorities were aware of such religious sensitivities. For instance, on religious occasions, the radio authorities temporarily halted music programs; the daily Iṭilā‘āt reported of “the removal of the radio’s music” due to the commemoration of Shiites’ second Imam and Islam’s Prophet, mentioning that, during the hours in which music was to be broadcast, there would instead be silence.[27] Although public performance of music had grown throughout Reza Shah’s reign, and the phenomenon of musicophilia, [28] i.e., the public performance, production, and consumption of music, and the collective listening of and writing about it, became a cultural feature of musical modernity in Iran, considerable sections of Iranian society remained religious even in the 1940s, and musicians did not necessarily enjoy a respectable social status. The memoirs of the famous vocal musician, Badeezadeh and his narrative on Abdolhoseyn Shahnazi testify to this. According to Badeezadeh, Abdolhoseyn Shahnazi, a famous tar performer faced a crowd’s anger in a Jewish neighborhood in Tehran during the early 1940s, which broke his instrument.[29] These powerful religious sentiments against music are also reflected in his account of Abdolhoseyn Shahnazi’s funeral; according to Badeezadeh, none of the Shiite clerics in Tehran were ready to perform his ceremonies, and finally the famous moderate cleric, Falsafi, accepted the task, but at the end of the funeral speech asked for the divine’s forgiveness for Shahnazi due to his profession.[30] These tales are an indication of how sections of Iranian society in the Tehran of the 1940s retained their religious sentiments even after the secularization of the public sphere under Reza Shah. Religious sensitivities among the public lingered even in later years, and sections of the public reacted to radio’s role in the promotion of music. A document addressed to the senate in 1951 by the Youth Committee of Merchants and Guilds vehemently criticized the speech of a senator who spoke against the decision of banning music’s broadcasting from radio during the month of Ramadan (Figure 8). The Committee expressed its “disgust and abhorrence” at the speech (Figure 8). Another letter followed by this request, and sent to Seyyed assan Emami, known as Imām-i Jom‘ah, the Shiite cleric who headed the seventeenth parliament at this time, requested the concerned authorities “to organize the undisciplined” programs of radio, omit the music sections, and instead include sections on health, religion, political, and ethical speeches, etc. The letter stressed that music is one of the prohibitions of the Sharia law, that it “makes the innocent youth of the country lecherous,” and inhibits them from seeking a “scientific and ethical position” (Figure 9). ence, the experiences of listening to radio generally, and to music specifically, were different in nature, and included such reactionary responses as well.

Source: National Library and Archives of Iran. (Figure 8.)

Source: National Library and Archives of Iran. (Figure 9.)

Iranian Music on Radio Tehran: 1940-1941 (The Formative Phase)

During this short but formative period in which policy makers were busy formulating the content of radio programs, Iranian music nevertheless became audible through Radio Tehran. Tehran’s radio programs in May 1940 show various rubrics: “Western music” performed by the bureau of music’s orchestra, “Iranian instrumental and vocal music” (sāz va āvāz Irani) by the “radio’s music performers,” and a few sections broadcasting gramophone records, and the royal anthem.[31] Beginning in Radio Tehran’s second year, a separate section for Iranian music appeared in its list of programs. owever, even in accommodating various musical genres, the radio authorities had limited choices and resources. Such limits were therefore not necessarily related to the varied tastes of policymakers, but rather stemmed from limited resources, even in the case of popular music. For instance, in a document dated March 1941, and signed by the deputy to the prime minister’s office, a purchase of “Arabic, Turkish, and Afghani records” is ordered for the Iranian ministry of foreign affairs. The order requested the ministry to navigate the best singers and performers of other countries who were popular among their people.[32]

Apart from such efforts to accommodate imported popular music records during this early period, specific schedules for the performance of Iranian music were allocated. The radio’s audiences were able to listen to the works of notable male musicians, including Aliakbar Shahnazi, Moshir-Homayun Shahrdar, Habib Somaei, female vocal musicians such as Qamarolmoluk Vaziri, Ruhangiz, and Ruhbaksh, and also the sound of ensembles performing Iranian music. An ensemble that appears in the documents is referred to as “the board of Radio’s musicians” or the “radio’s music ensemble.” This group, which performed in the Homayun mode, is listed as a performer of Iranian music on the radio’s programs, and is featured in the annual festival of the organization for the cultivation of thought in April 1941.[33]

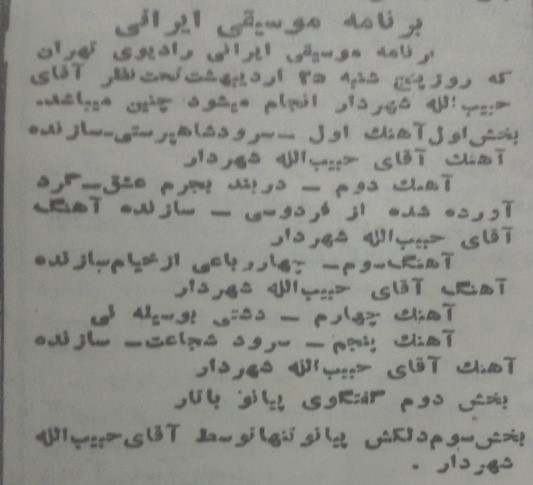

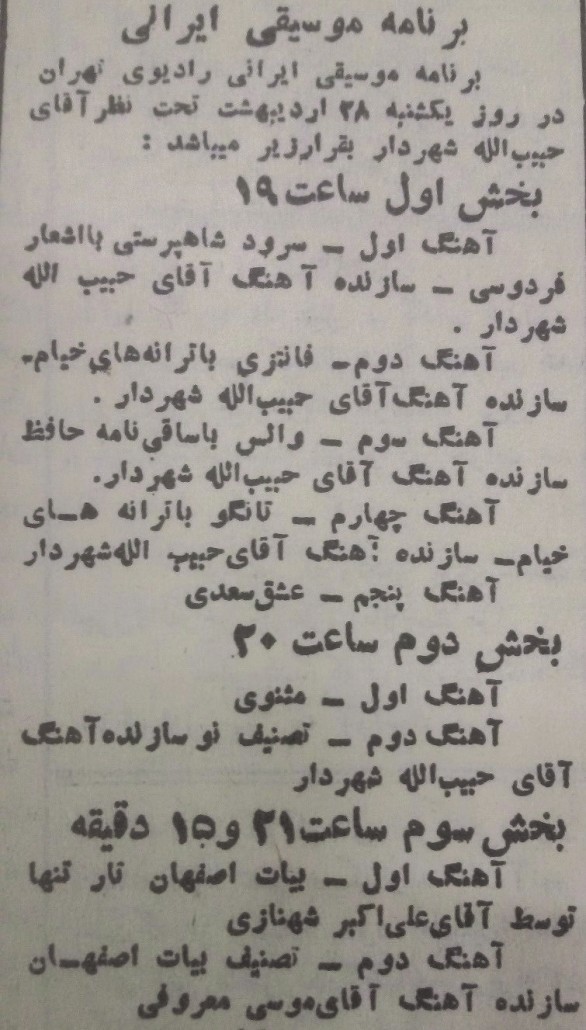

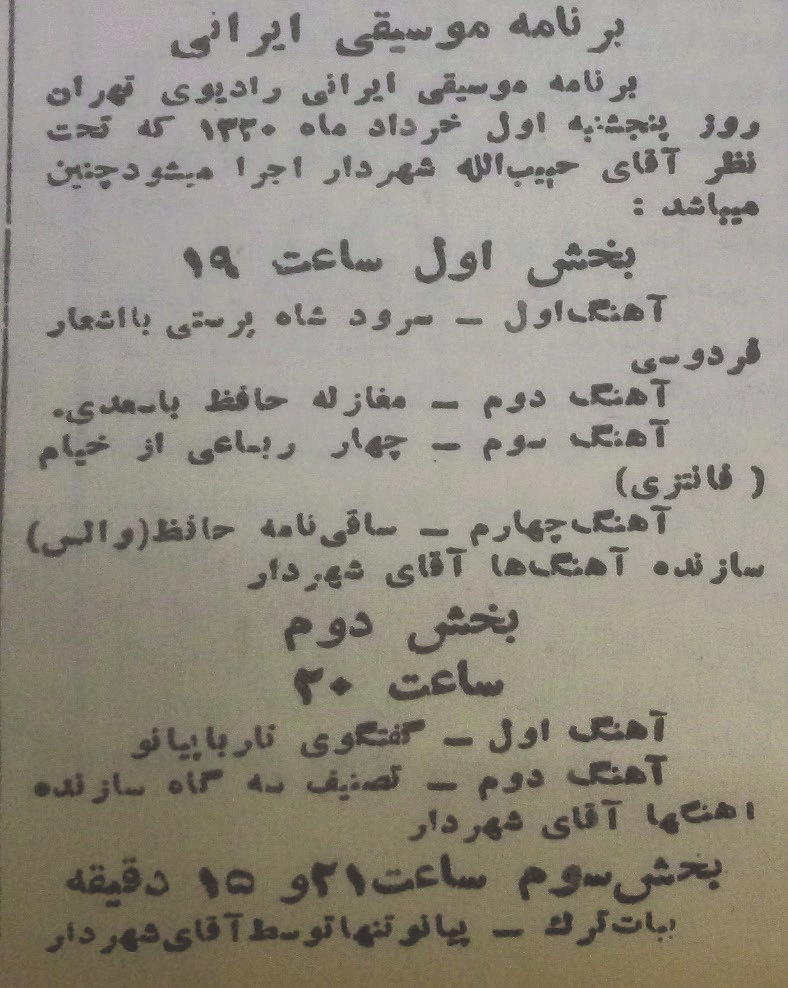

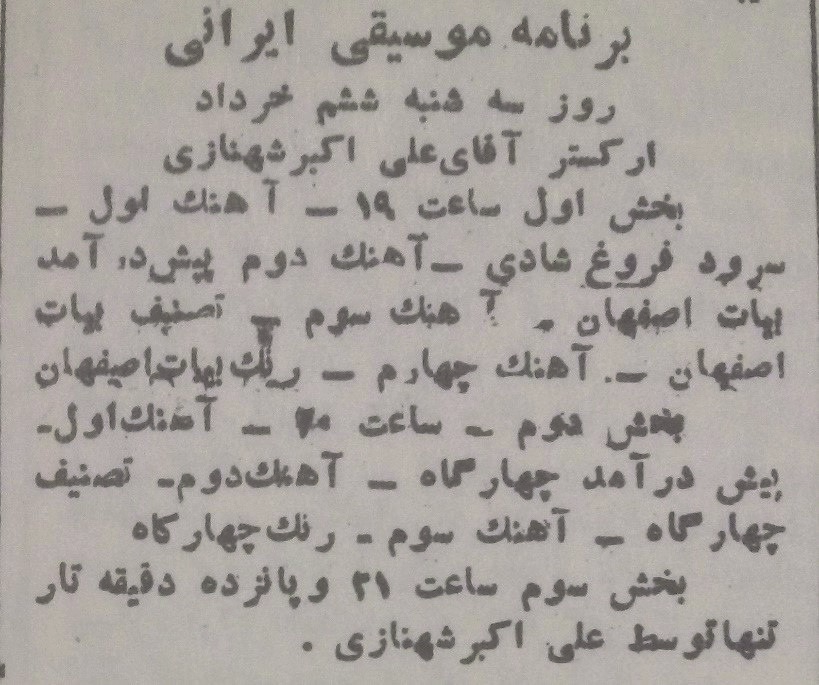

However, as I mentioned earlier, the foundation of radio led to the increased audibility of Iranian music within specific time schedules, which was important specifically for the sociability of Iranian art/ classical music given radio’s wide outreach. In what follows, I consider a few advertisements titled “The Program of Iranian Music” featuring Moshir Homayun Shahrdar, and Ali Akbar Shahnazi, and I show how the musical content of these programs was distinct and featured both Iranian art as well as popular compositions separately in different schedules. One of Moshir- Homayun’s performance sessions consisted of an official tributary song, two rhythmic vocal songs or taṣnīf, composed by himself on the poems of Ferdowsi and Khayyam, a ney solo, a duet with tar, and finally a solo piano performance.[34] The program featuring Shahnazi on May 27, 1941 details his performance session as follow: in the first section Shahnazi and his ensemble performed a popular song titled “Forugh-i shādi,” further to a pīshdarāmad, taṣnīf, and ring in Isfahan mode, all of which constitute the core repertory of Iranian art/classical music. The second section consisted of pīshdarāmad, taṣnīf, and ring in the chahārgāh mode. In the final section of the program, Shahnazi also performed a solo for fifteen minutes.

Iṭilā‘āt. May 14, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt (Figure 10.)

May 17, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 11.)

May 21, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 12.)

May 26, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 13.)

During this short but formative stage, the radio became a space where female vocal musicians of the Reza Shah period, such as Qamarol-Moluk Vaziri, Ruhangiz, and Ezzat Ruhbakhsh performed, and whose voices could be heard by larger masses. While nearly all instrumental performers were male, female vocal musicians’ presence was an interesting aspect given radio’s large coverage. Generally, the entire period under discussion marked an era where the gendered dichotomy in vocal music performance between āvāz and taṣnīf—as it appeared later in the mid 1950s—had not been yet formed.

A document dated February 26, 1941 lists Ruhangiz as a performer of vocal music under the section titled, the “Iranian instrumental and vocal music program” (sāz va āvāz Irani).[35] In another interesting document, the deputy of the radio’s commission, in a letter addressed to Radio Tehran’s subcommittee, conveys a series of decrees ordered by princess Shamas Pahlavi to the radio’s commission. The second clause of the order mentions that the vocal music of two female vocalist, namely Behzadi—a relatively unknown figure—and the famous and prolific vocalist of Reza Shah’s period, Qamarolmoluk Vaziri, is endorsed, and the decree further asked the subcommittee to recruit these two female vocal musicians.[36] Such decrees show that the administration of radio at this time was not solely dependent on the decisions made by music authorities such as Minbashian, and that decision-making in accessing the pathways of radio was in fact a more complex process.

From Left to Right: Mehdi Qiasi, Ruhangiz, Hoseyn Yahaqqi, Unknown, Lotfollah Majd,

Unknown, Javad Lashkari. Radio’s Studio, 1940s. Personal Collection. (Figure 14.)

Iranian Music in Radio Between 1941-1942

In this section, I follow the question of Iranian music’s audibility from Radio Tehran, and show how Iranian music, specifically vocal and instrumental music, were prominently heard from that platform. Reza Shah’s resignation in September 1941 heralded various transformations in the cultural, political, and administrative sphere in Iran, including transformations in the radio’s administration. One immediate result was the reemergence of Vaziri at the administrative level of music in the country, and his presence in radio. One of Vaziri’s very early initiatives in this period was founding the modern orchestra or urkistr-i-nuvīn in radio. The orchestra began its activities in radio from November 1941 and performed twice a week on Radio Tehran.[37] Vaziri, in his November 24, 1941 speech on the radio, described the music of this orchestra as “Iran’s new music in a newly founded orchestra, with the aim of reaching audiences’ ears.” In this speech, he expressed that music must be ‘revived’ based on what he called “scientific methods.” He described his modernist goals for Iranian music as follows:

The music of Iran should not be sacrificed for European music. The only aspect of European music useful for us is to base our music on the methods and foundation of European music, and to make it scientific, so that it can be taught in any school. Over the past one-and-a-half months that I have been appointed in charge of a job that I always admired […] I have established […] an orchestra. The orchestra’s repertory is based on the foundations of Iranian music, but from a scientific perspective, and it is based on international music, which is to say […] [it] has harmony, and unlike the usual approach in Iranian music, it is not monotonous.[38]

Despite the significance of orchestration and Vaziri’s ‘scientific’ approach to Iranian music, the majority of Iranian music performances broadcast on Radio Tehran from 1941 until late 1942 were of vocal art/ classical music performed by noted vocal musicians, and instrumental performances of solo or smaller ensemble musicians. In other words, although Vaziri represented the modernist narrative of Iranian music in which the question of orchestration was significant, in these years it was instead āvāz and solo performances that were widely performed.

The bureau of music too had requested the “local performers of the provinces to perform their regional music on radio,” and invited the famous ney performers of Reza Shah’s period, Mehdi Navāei from Isfahan, and Rahim Qanuni from Shiraz, to perform on Radio Tehran.[39] This announcement stated that “the best performers and singers of each city, specifically the performers of the national and old musical instruments that are common in between the villagers,” are invited to perform on radio.[40] Clearly, this request did not lead to invitations of regional folk musicians to the radio, but in fact, in the first two years it was—as previously mentioned—specifically well-known musicians of Iranian vocal and instrumental music who performed. The weekly Iṭilā‘āt began listing radio performances following Reza Shah’s resignation. These programs show distinct performances that involved important sections from the repertory of Iranian art/classical music that included pīshdarāmad, vocal sections, taṣnīf and instrumental chahār’mizrāb, and ring forms.[41]

Such a strong presence of Iranian art/classical music, specifically vocal and instrumental music, resulted in objections by various audiences, and from other music activists. For instance, an advertisement sent to the daily Iṭilā‘āt titled “The New Program in Radio,” shows the dissatisfaction of some of radio’s audiences from what it claimed to be the “exclusion of the European music section from the end of the daily music program.” The letter further demanded that the bureau of music, but also Vaziri, pay attention to this situation.[42] As Fayyaz shows, one of the issues at this time—that is after Reza Shah’s resignation—in radio’s management was the contestation between two wings in the musical administration of radio: on the one hand, the Vaziri-Khaleqi wing that represented a modernist narrative of Iranian music, and, on the other hand, a new wing that promoted Western classical music, represented by Parviz Mahmud. Vaziri was in fact at the center of these criticisms, since in the eyes of the critics, he represented Iranian music. Harsh criticism came from Ataollah Zahed, who sent a letter from Tehran’s theater hall to Radio Tehran, addressing Abutaleb Shirvani, the general chief of the bureau of publication and radio. In this letter, he severely criticized radio policies, to which he attributed Vaziri’s presence at the level of decision making. Zahed claimed the situation of music, since Vaziri’s take over, has become worse than before.[43] He raised five critical points about radio’s music programs, and accused Vaziri and Khaleqi to have “purposefully made people listen to and experience the music of Iran as dreary, and have made the world weary of our music.”[44][45] The manifestation of “dreary music,” according to him, was the vocal music of the famous vocal musicians performing Iranian art/classical vocal music on radio. He objected by asking why, in such a vast country, only a few “old and scrap singers” should perform on radio. He wrote:

For instance, consider how much a person could at any point of time, upon switching on the radio, listen to Iranian music, and be compelled to listen to a performance in Sah’gāh by Rubakhsh, an Isfahan by Adib Khansari, or a Shur by Badeezadeh, or a Bayat Tork by Ruhangiz, or Homayun by Taj or the songs Kharīdār-i tū and nīm-i shab by Abdol’ali Vaziri (a relative member)!!! Never mind how perfect and excellent these performances are.49

The fierce criticisms Zahed raised against the radio’s music targeted Vaziri. But at the core of Zahed’s criticism are his objections against the centrality of Iranian music generally, and specifically vocal classical music, and its performers. Zahed’s criticisms showcase a reality: the primacy of Iranian vocal and instrumental classical music. This was something that he considered Vaziri to be responsible for, but did not realize that such performances indeed constituted the main capacity of Iranian music at the time and even in the years to come.

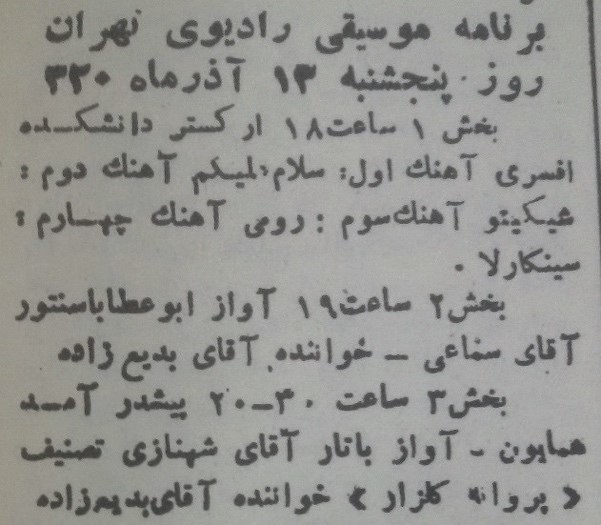

As I mentioned in the previous section, with the establishment of Radio Tehran, the performance of Iranian music within specific time schedules became important. It is in this period that such a conception of performance in specific time schedules gains even further importance with more regular performances. Both Iṭilā‘āt and Iṭilā‘āt–i–Haftegi published the list of programs of radio from the fall of 1941 until at least 1942.[46] Vocalists such as Taj, Adib Khansari, Badeezadeh, Qamarolmoluk Vaziri, and Ruhangiz were prolific during this period. Free metered vocal music,[47] and metered vocal music or taṣnīf, instrumental pieces such as pīshdarāmad and ring, were performed frequently. Iṭilā‘āt, in its advertisement of the radio’s programming, details these programs, and I will briefly describe a selection of the performance sessions. In a program dated November 30, 1941, in the first section Ruhangiz performed with Abolhassan Saba’s violin in the sah’gāh mode; the performance repertory included a pīshdarāmad, free metered vocal music, and a taṣnīf. The second program of the day also featured Ruhangiz, but with the tar performed by Neidavud. In the third section of the day, urkistr-i nuvīn performed various pieces, including popular pieces such as marsh, waltz, but also a taṣnīf that was performed by the vocal musician Abdol’ali Vaziri. Another program dated December 4, 1941 listed two sections; the first section involved a performance by the college of officers’ orchestra that featured four songs during the first hour of the day. But during the second time slot of the radio’s program, the famous Santur performer, Habib Somaei, performed for an hour along with Badeezadeh’s vocal music in the abūʿaṭā mode. The second section of the same day again featured Badeezadeh with Ali-Akbar Shahnazi who performed in Humayūn mode; the performance involved a pīshdarāmad, an āvāz, and ended with a taṣnīf titled “Parvānah-i gulzār.” The program dated December 11 had three sections: in the first section, the officers’ orchestra appeared on radio; in the second section, Habib Somaei, along with the vocal musician Taj-i Esfahani,[48] performed in the Bayāt-i turk mode, and finally in the third section, Taj again performed with Ali-Akbar Shahnazi in the sah’gāh mode; this latter performance session included a pīshdarāmad, an āvāz section, and a final ring as the closing section.[49]

Radio Tehran’s programs. November 29, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 15.)

Radio Tehran’s programs. December 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 16.)

Radio Tehran’s programs. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 17.)

December 29, 1941. Source: Iṭilā‘āt. (Figure 18.)

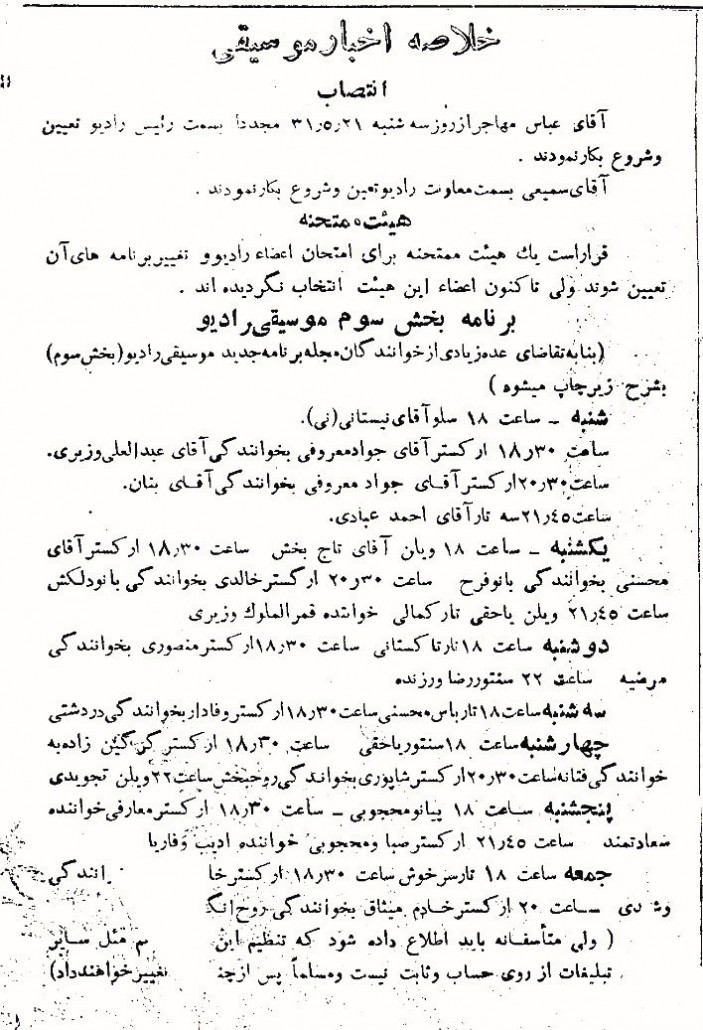

Iranian Music on the Radio: From the Mid-1940s to the Early 1950s

Iranian music remained an important component of the radio’s programs from the mid 1940s until 1951. This period has often been overlooked given the lack of sufficient documents and sources. In this section, I situate my earlier argument based on a few published documents, and also several recently found documents of the radio’s programs. Sections titled, “Iranian music,” “solo” and “Iranian ensemble,” or orchestra, are frequently mentioned in these documents. It is finally the political crisis during the oil nationalization movement that marginalized music, including Iranian music performed on radio.

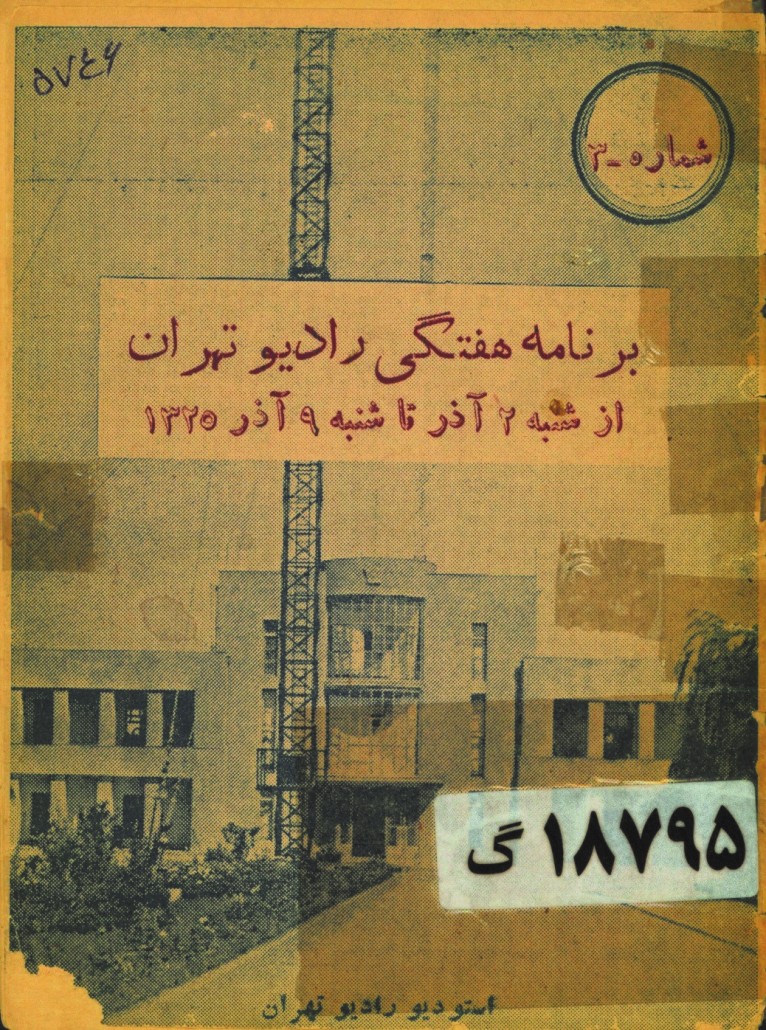

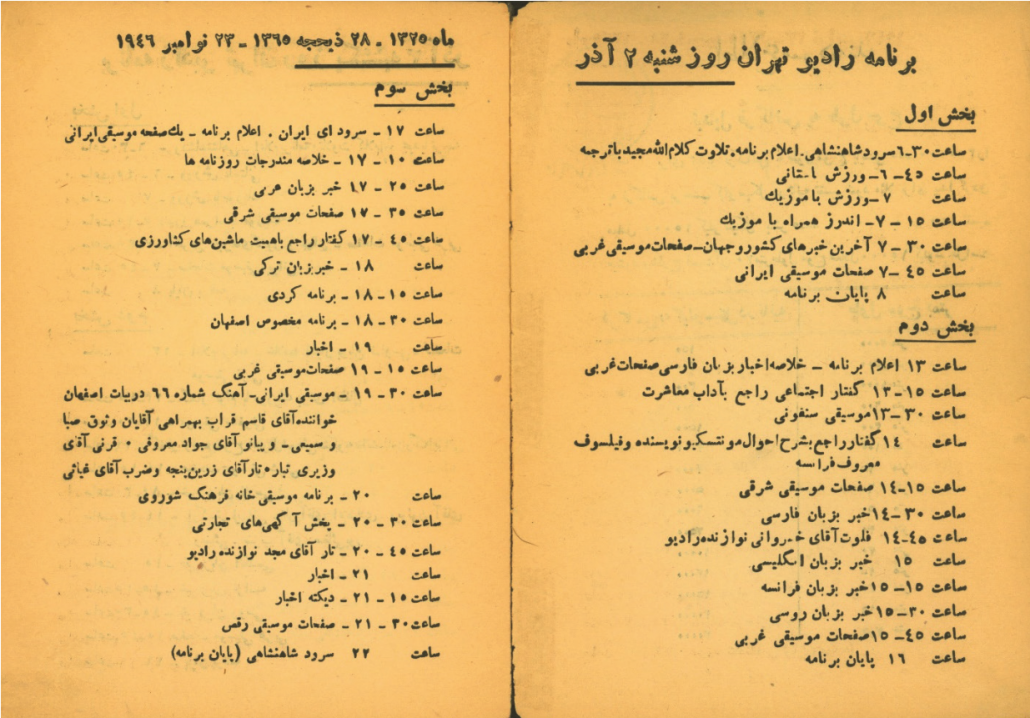

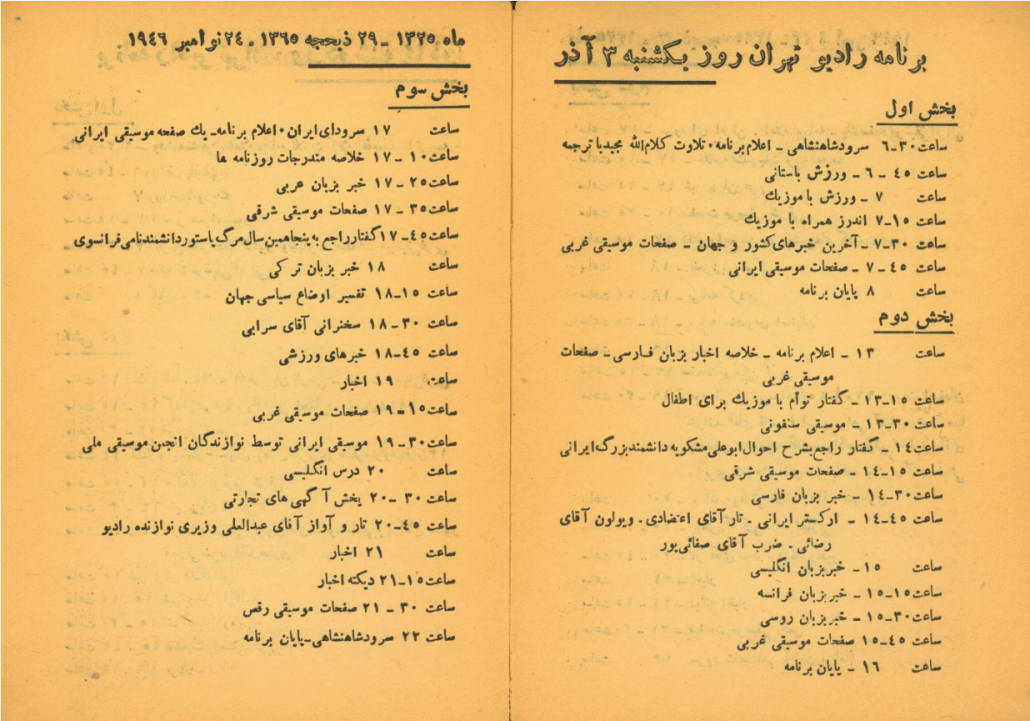

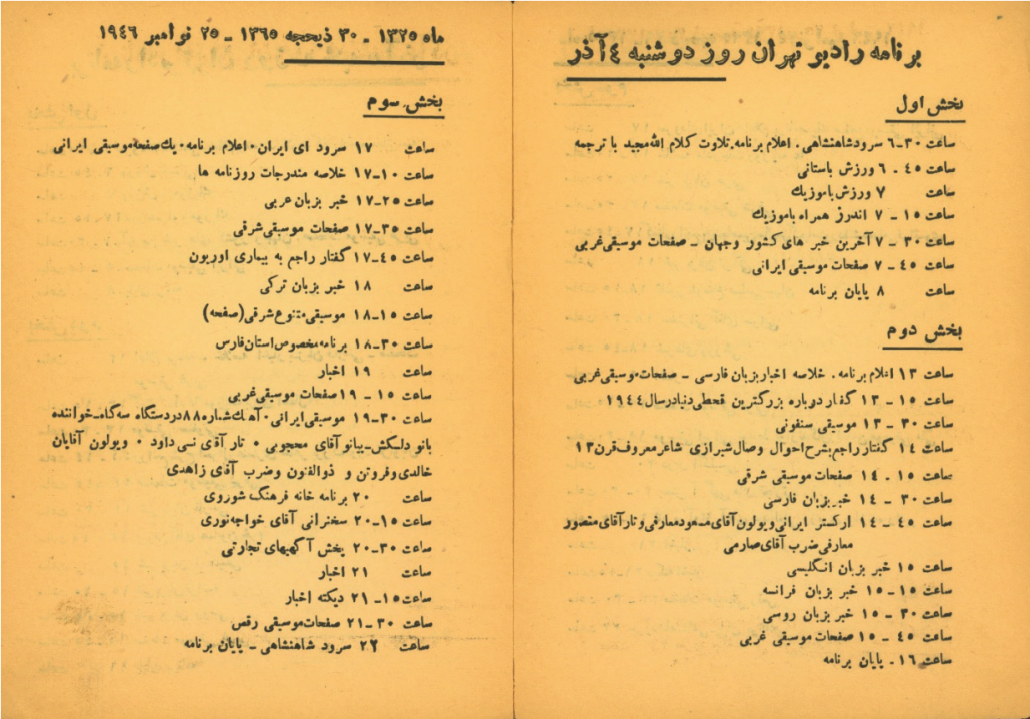

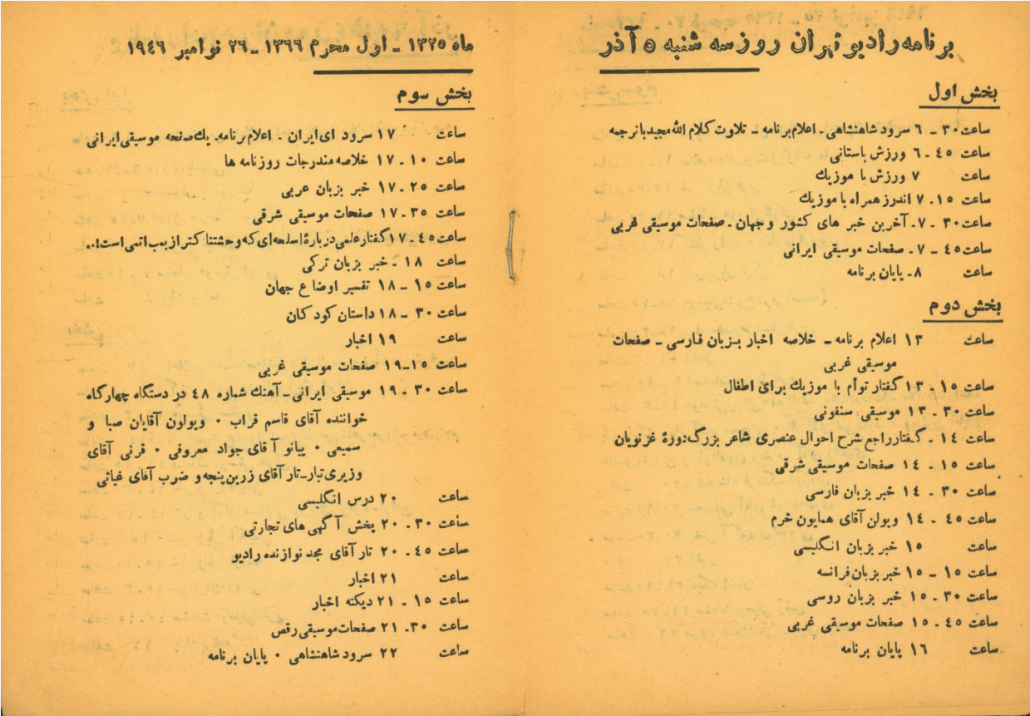

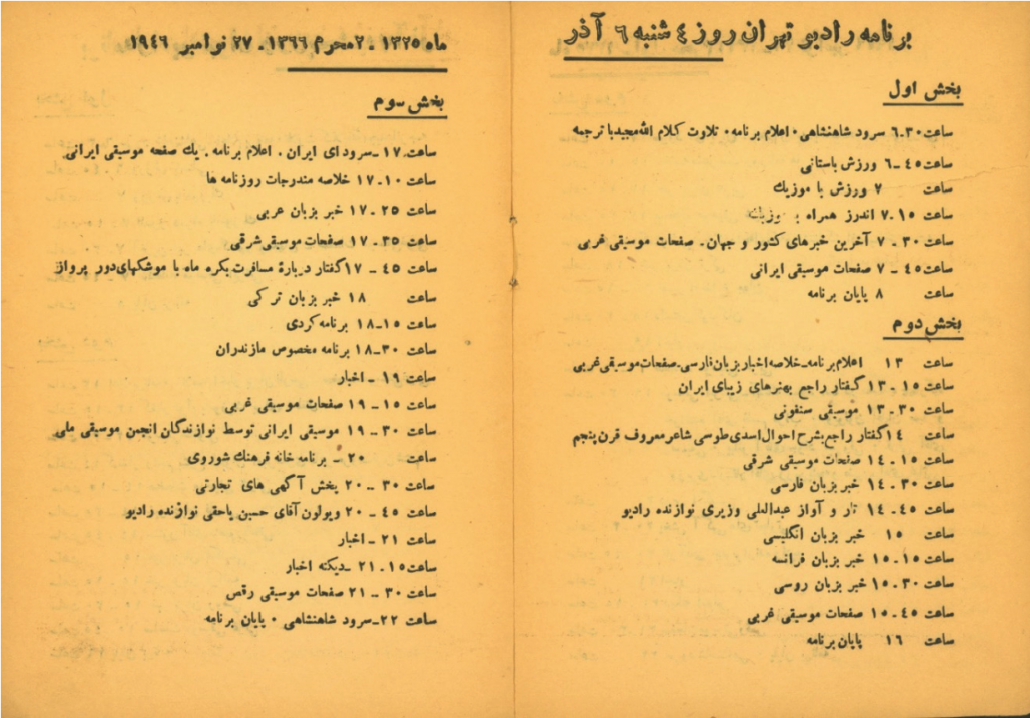

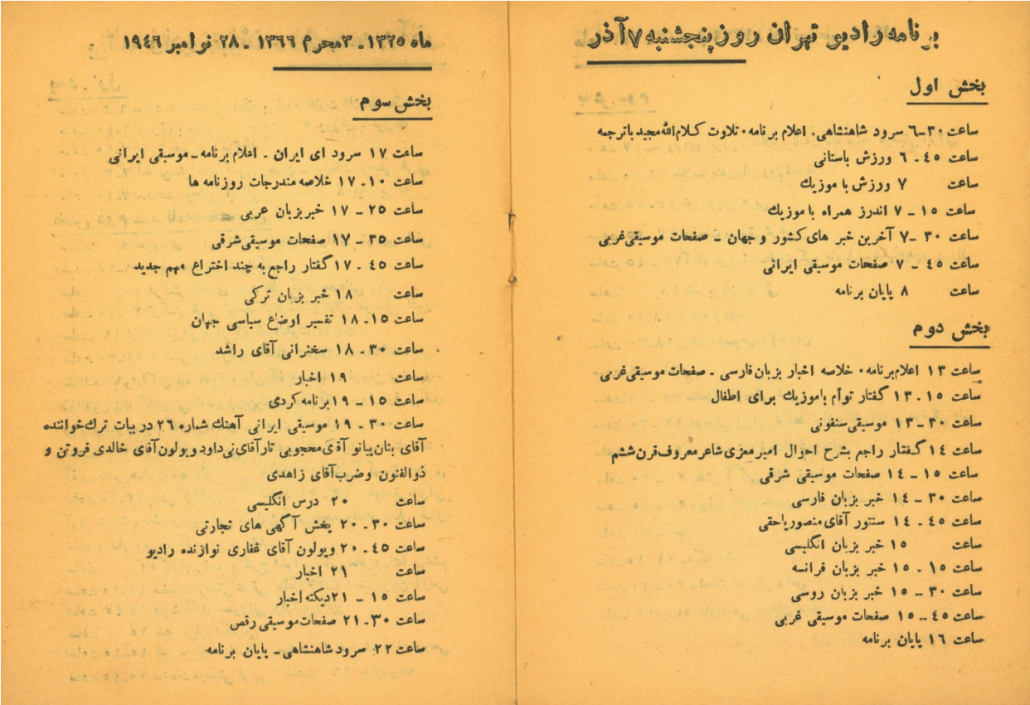

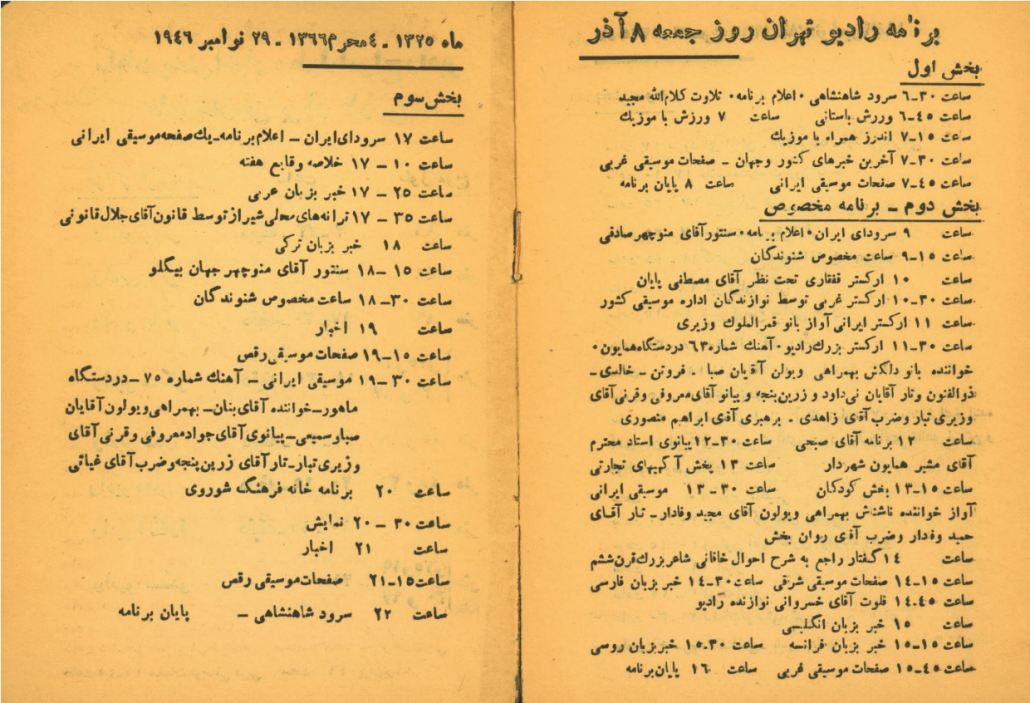

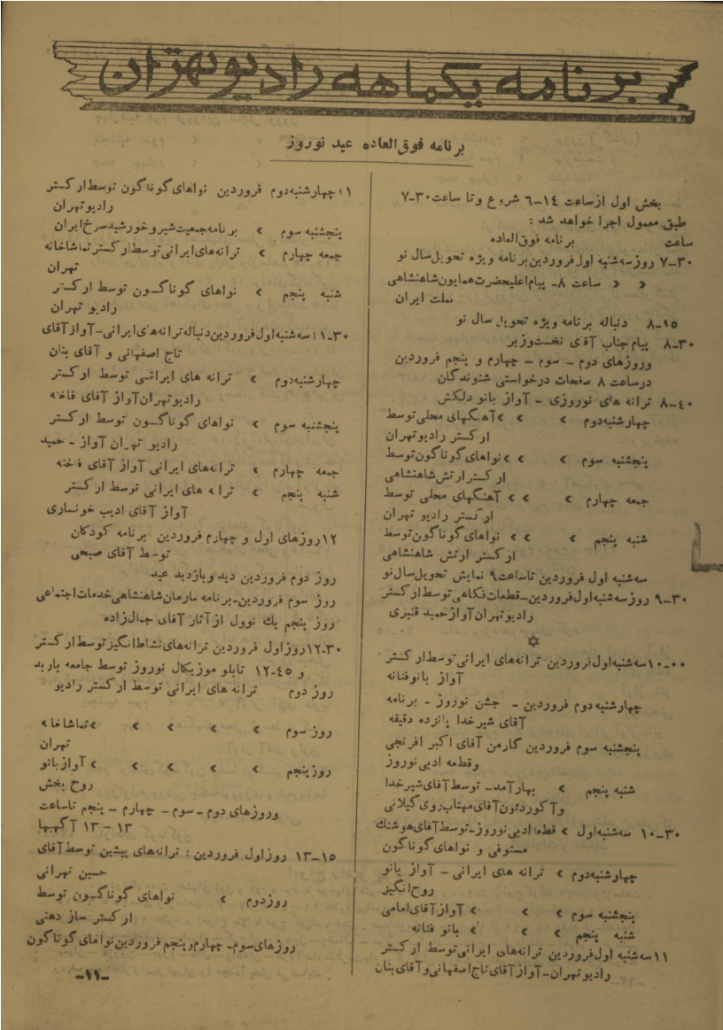

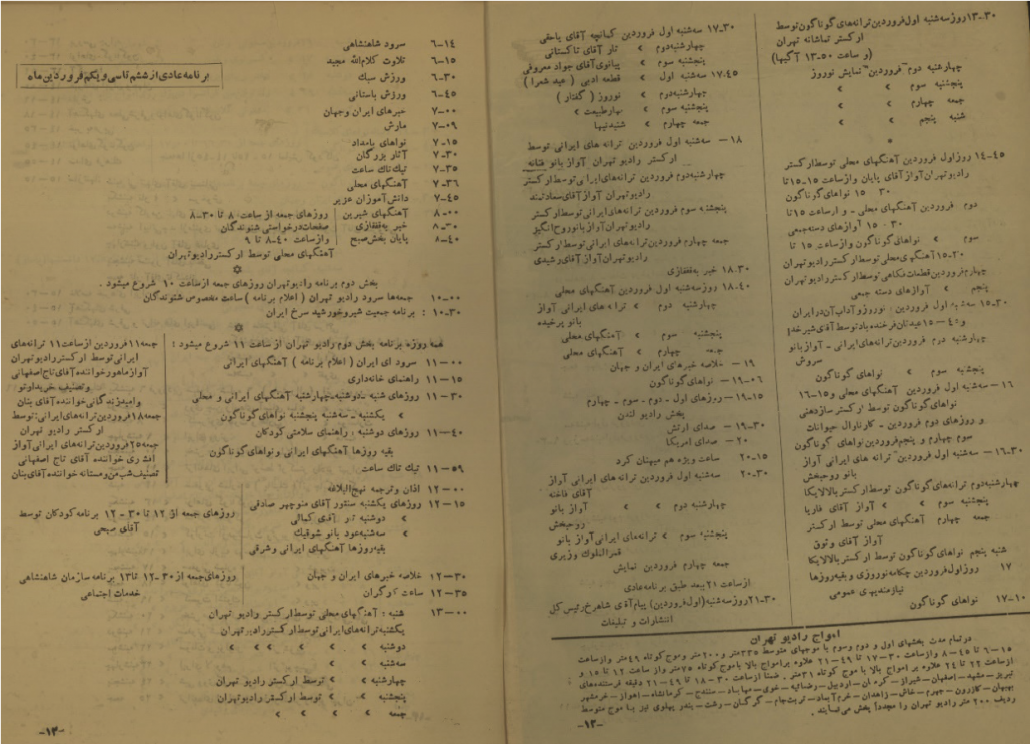

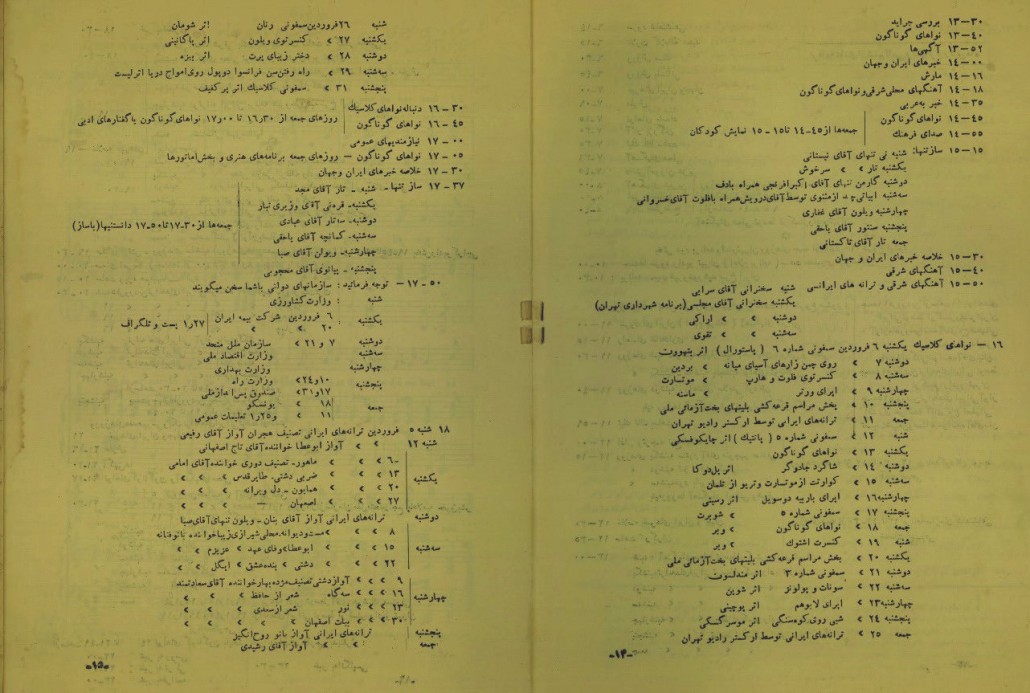

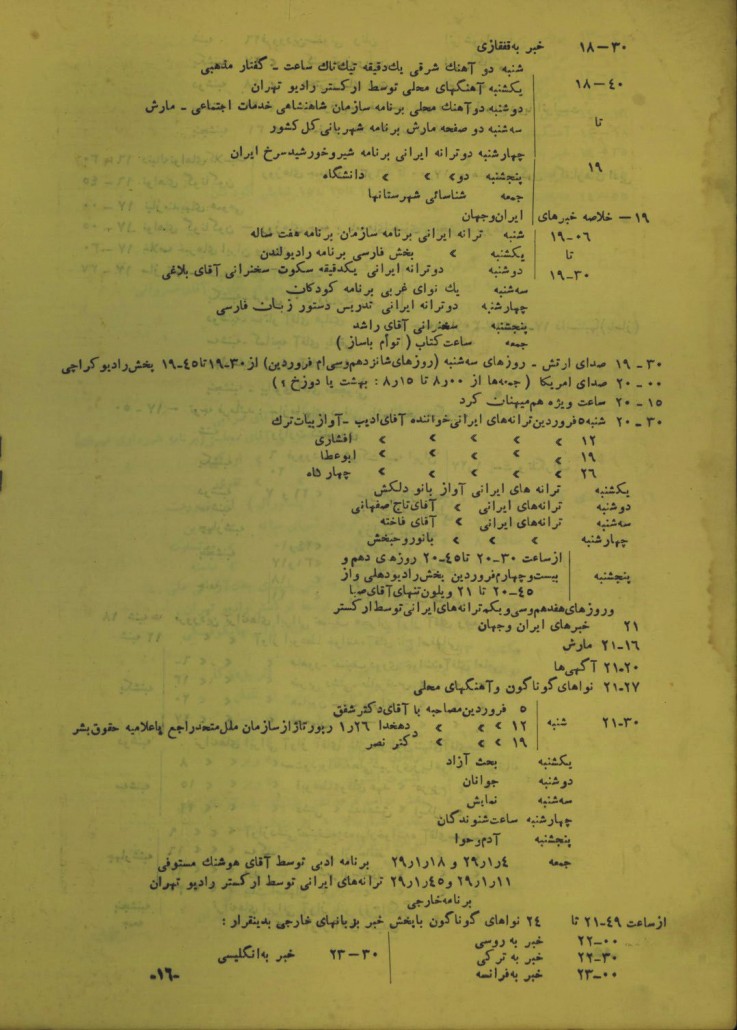

Three recently found catalogues of Radio Tehran outline radio programming in 1946, 1947, and 1950. The first catalogue, dated November 23-29, 1946 shows the regular presence of noted Iranian musicians; these include figures such as Abolhassan Saba, Hoseyn Yahaqqi, Morteza Neidavud, and Hassan Khan Etezadi.[50] The general term “music” appears on several sections of the programs, and a few sections feature musicians performing Iranian music. A separate section details the broadcast of “Iranian music records” on different days, which most likely entailed the broadcasting of music from the 78rpm gramophone records of Reza Shah’s period. The 1947 catalogue titled īnjā Tehran Ast contains several sections under the titles “Iranian music,” “solo instrument,” “Iranian orchestra,” and “Iranian music records,” but does not refer to specific names of musicians. This catalogue, however, provides a few interesting visual documentations of the performers. Finally, the last catalogue titled Ṣidā-yi Tehran, dated 1950, illustrates the radio programs in the month of March, and provides detailed information about various radio musicians.

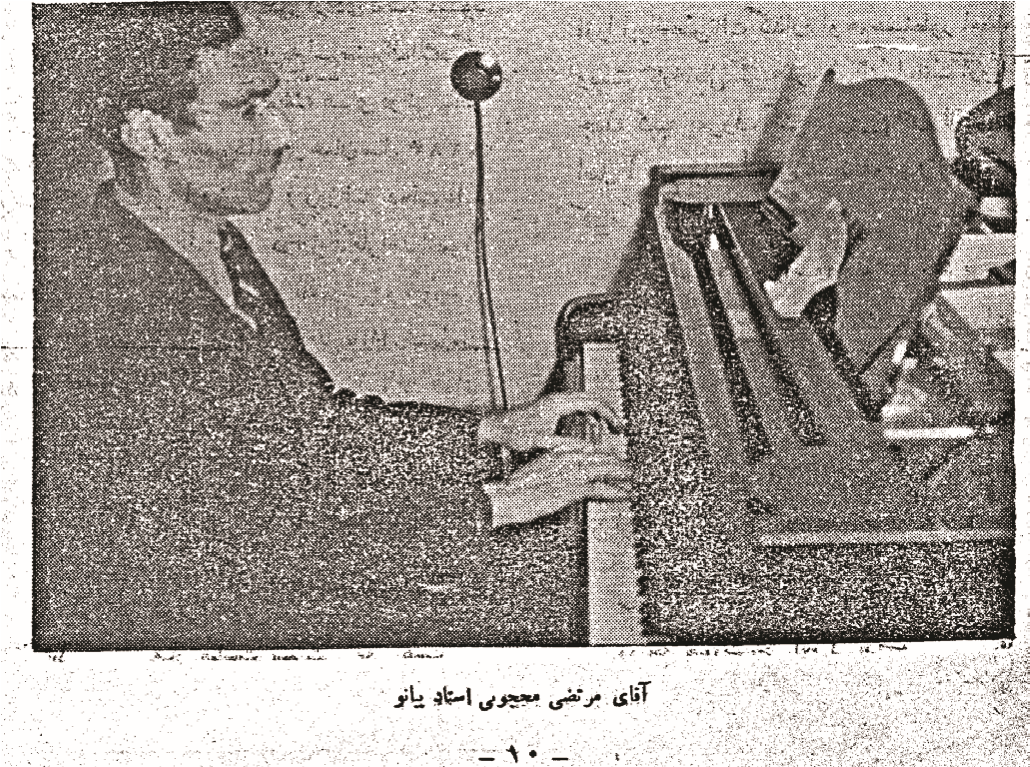

Morteza Mahjubi, performing in Radio Tehran’s studio. 1947. Source: Injā Tehran Ast:

Morteza Mahjubi, performing in Radio Tehran’s studio. 1947. Source: Injā Tehran Ast:

Radio Tehran’s Magazine. Personal Collection. (Figure 19.)

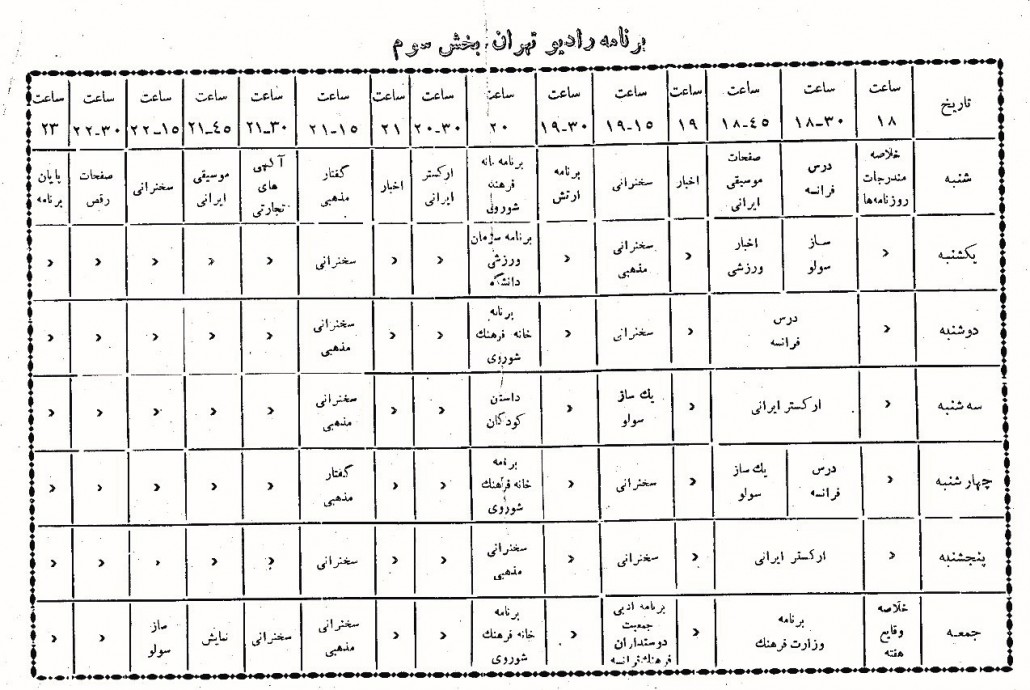

A chart of Radio Tehran’s programs. 1947. Injā Tehran Ast. Personal Collection.

(Figure 20.)

The National Association of Music, founded in the summer of 1944,[51] performed on several occasions on radio during this period. Chang, the magazine of the National Association, reported that the orchestra of the association had performed four times on radio until 1946. In November 1944, nearly five months after the foundation of the national association, the orchestra led by Khaleqi, along with two vocal musicians, Yahya Motamed-Vaziri and Abdol’ali Vaziri, performed on radio.[52] A few years later, in 1941, after the attempted assassination of the Shah in front of the Faculty of Law at the University of Tehran, Khaleqi conducted the orchestra of the association along with the vocal performance of Qolamhoseyn Banan, and Maleke Hekmat-Shoar, as a tributary performance to the monarch’s health. The orchestra also performed a song for the nationalization of oil in May 1951.[53]

Throughout the latter half of the 1940s, smaller ensembles of Iranian music proliferated and performed on radio. All the mentioned catalogues refer to some of these ensembles. For instance, on November 23, 1946, the third part a separate section marked under the rubric of “Iranian music,” Qasem Qorab, along with an ensemble including Abolhasan Saba, Javad Ma’rufi, Vosuq, Somaei, Vaziritabar, Zarpanje, and Mehdi Qiasi, performed on the radio in Bayāt Isfahan mode. Qasem Qorab and the same ensemble appeared once again in the programs dated November 26 and performed for half an hour in Chahārgāh mode. The same ensemble accompanied Qolamhoseyn Banan, an emerging male vocalist of the 1940s in another “Iranian music” program for half an hour. Another program, titled “Iranian orchestra,” featured another ensemble consisting of I’tiẓādī on tar, Rezaei performing violin, and Safaeipur with tonbak. In the programs dated November 25,1946, the Ma’arefi brothers’ ensemble appeared in the second section. A letter dated November 1, 1947, and signed by Moshir Homayun Shahrdar, as head of Radio Tehran’s music council, requests Yahya Niknavaz to conduct a newly founded orchestra. According to this letter, other members include the famous tar performer Esmaeil Kamali, Kordbache, Mansur Yahaqqi, Asadi, Mehdi Qiasi, Khosravani and vocal musicians Yunes Dardashti and Manuchehr Shafiei.[54] The 1950 catalogue shows an increase in musical performances on the radio, and includes references to various smaller ensembles and orchestras including Tehran’s radio orchestra, and the Barbad Society’s ensemble.[55]

Solo performances of Iranian music were part of the radio’s programs and many soloists performing Iranian music were featured on radio. In the third section of the programs dated November 23, 1946, Lotfollah Majd, one of Radio Tehran’s prolific future tar soloists performed for fifteen minutes. Majd also appeared in another solo performance, lasting fifteen minutes, and dated November 26. The 1950 catalogue also shows that Majd was one of Radio Tehran’s soloists. On November 29, 1946, Manuchehr Sadeqi performed a solo performance for fifteen minutes under the second section of the day’s programs, titled “special program.” Another solo performance of Iranian music on the same date featured the famous piano performer Moshir-Homayun Shahrdar, who performed for half an hour. Hoseyn Yahaqqi, one of the important figures of Iranian art/classical music who performed mainly violin, but also Kamānchah, contributed to the solo performances by way of a fifteen-minute section on November 27, 1946. Mansur Yahaqqi mentions that in the middle of the 1940s, Khaleqi requested his uncle, Hoseyn Yahaqqi, to perform and ‘revive’ the kamancheh, which had been undermined by the violin in Iranian music.[56] In fact, Hoseyn Yahaqqi’s name appears as a kamanche soloist in Radio Tehran’s solo performance programs on Tuesdays in 1950. The 1950 catalogue lists a separate section for solo performances. Apart from Hoseyn Yahaqqi, Abolhasan Saba, and Morteza Mahjubi, who had appeared in earlier radio programs, the end of this period marked the emergence of a new generation of soloists as well. Tar performers such as Mehdi Takestani, Esmail Kamali, and Ebrahim Sarkhosh, the piano performer Javad Ma’rufi, and Ahmad Ebadi on setar. Many of these names also appear in the list of Radio Tehran’s programs published in the monthly Mūsīqi-i Iran in 1952.

The radio gradually welcomed a younger generation of musicians and soloists. One of the youngest emerging musicians whose name appears among the contributors to Radio Tehran’s music programs is Homayun Khorram, a noted apprentice of the famous violin performer Abolhassan Saba, who performed for fifteen minutes on November 26, 1946. Manuchehr Jahanbeglu, another young musician, performed on santur in a fifteen-minute section on November 29, 1946. There are many documents regarding the participation of Mansur Yahaqqi, a young santur performer and one of Habib Somaei’s apprentices from the mid-1940s. Mansur Yahaqqi recounts that in the mid-1940s, Ruhollah Khaleqi met him at his uncle Hoseyn Yahaqqi’s house, and that Khaleqi invited him to perform a santur solo during the interludes of the national association’s orchestra. A document presumably dated around the same time, and signed by Ruhollah Khaleqi, requests Mansur Yahaqqi to perform on the radio.[57] Another document signed by one of Radio Tehran’s head of programs on August 4, 1946 asked Mansur Yahaqqi to perform a santur solo on air on the occasion of the constitutional revolution on August 5, 1946.[58] His name also appears among the radio’s young santur soloists, in a program dated November 28, 1946, in which he performed for fifteen minutes in the second section of the radio’s programs. Mansoor Yahaqqi also points to an invitation letter handed over by Khaleqi to perform santur on Radio Tehran; the invitation letter issued by the general bureau of publication and propaganda requested Mansoor Yahaqqi to be present at the Radio Tehran festival on April 25, 1947, on the occasion of the eight-year anniversary of the radio’s inauguration.91 Mansur Yahaqqi’s name also appears as part of Yahya Niknavaz’s ensemble.

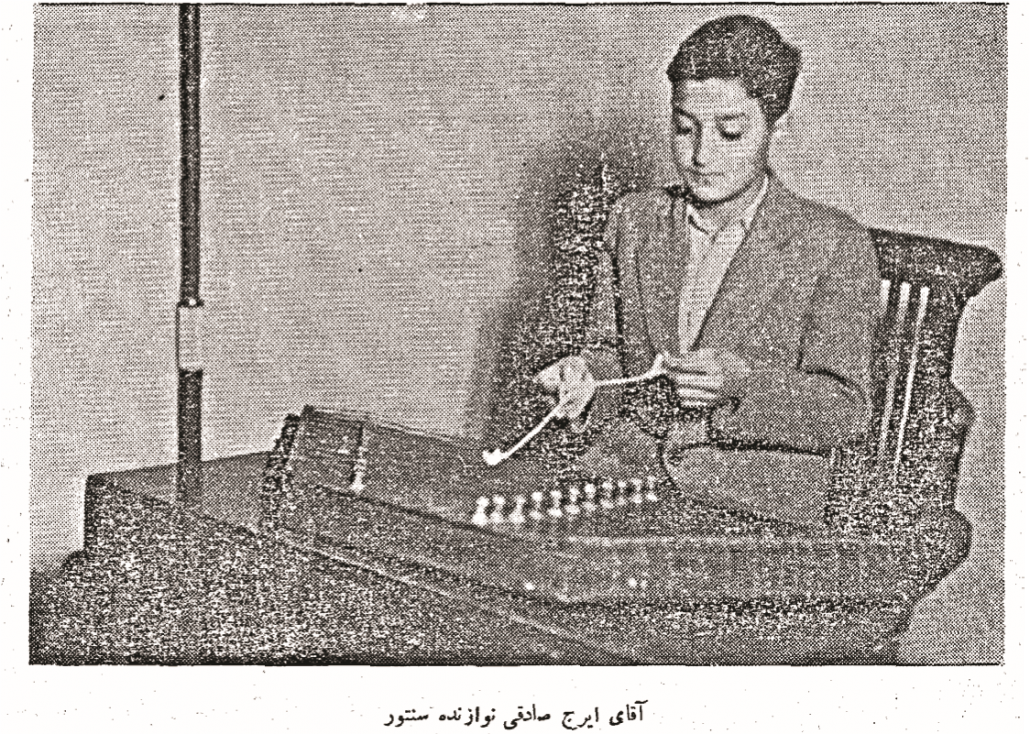

Iraj Sadeqi, a young santur performer at the studio of Radio Tehran. Injā Tehran Ast.

Personal Collection. (Figure 21.)

Famous male vocal musicians continued their performances from time to time on radio until the latter part of this period. Abdol’ali Vaziri featured on radio with his tar and vocal music performance at the end of the third section. Apart from the famous vocal musicians of Iranian music such as Adib and Taj, a new generation of Iranian vocal musicians who performed art/classical vocal music found their ways to the hallways of the radio’s studio. Seyed Javad Zabihi, a famous vocalist also associated with Tehran’s religious circles, began his career in the late 1940s and early 1950s in radio and performed vocal music with religious and spiritual content. Two other male vocal musicians who performed on radio at the end of the 1940s and during the early 1950s are Yunes Dardashti and Mohammad Emami.

Female vocalists continued to contribute to the radio’s Iranian music performances. The names of Qamarolmoluk Vaziri and Ruhangiz, two performers of the earlier generation, again appear among radio’s female vocal musicians during these years. Qamarol-Moluk Vaziri’s name appears in the second section of November 29, 1946, under the title of the “Special Program.” In this program, Qamar featured along with an “Iranian orchestra” for half an hour. In the second brochure of the radio’s programs dated 1950, her name appears among the vocalists of Radio Tehran on March 23. Ruhangiz’s name appears as vocal musician on Radio Tehran during the final years of the 1940s. Her name does not appear in the current list of programs available from the mid-1940s, but from what is available from 1949 on, it is certain that she began her performance career in radio. Ruhangiz was a regular performer in one of Tehran’s famous cafés known as Jamshid. She ostensibly stopped performing there in order to resume her performances on radio in the latter half of the 1940s. The daily Iṭilā‘āt, in an advertisement about Ruhangiz, mentions that she has stopped performing at the above mentioned café, and that she has commenced performing on Radio Tehran.[59] A new generation of female vocal musicians performing Iranian music gradually emerged from the mid-1940s on. In the catalogue dated 1946, Delkash, a female vocalist who had emerged in the 1940s, performed in sah’gāh mode along with one of the important ensembles of Iranian music consisting of Morteza Mahjubi on piano, Neidavud on tar, Mehdi Khaledi, Forutan and Zolfonun on violin, and Zahedi on tonbak.

Cover of the Catalogue of Radio Programs, November 23-30, 1946.

Source: Majlis Library. (Figure 22.)

1946 Catalogue. November 23. (Figure 23.)

Catalogue. November 24. (Figure 24.)

1946 C atalogue. November 25. (Figure 25.)

Catalogue. November 26. (Figure 26.)

1946 Catalogue. November 27. (Figure 27.)

1946 Catalogue. November 28. (Figure 28.)

1946 Catalogue. November 29. (Figure 29.)

1950 C atalogue. Personal Collection. (Figure 30.)

1950 Catalogue. Personal Collection. (Figure 31.)

1950 Catalogue. Personal Collection. (Figure 32.)

1950 Catalogue. Personal Collection. (Figure 33.)

Radio Music Programs. 1952. Source: Mūsīqī-yi Iran. (Figure 34.)

Conclusion

In this article, I examined Iranian music on the radio in the first decade of the latter’s establishment in Iran, showing how music performance within specific schedules was a crucial part of radio programming. Iranian music, including Iranian art/classical music, was audible throughout this period. Instrumental forms such as pīshdarāmad, ring and taṣnīf, and Iranian free metered vocal music known as āvāz alongside metric vocal pieces, were broadcast for a broader audience. While radio is predominantly considered as a medium in the dissemination of popular music, at least during the first decade of its establishment in Iran, it led to the wider listening experience of Iranian music, including Iranian art music.

[1] I must thank my mentor, Dr. Dariush Rahmanian from the history department of the University of Tehran, Mardomnameh’s editor-in-chief, and Jane Lewison, Director of the Golha and Golistan Projects, for their invaluable support and guidance.

[2] Meltem Ahiska, Occidentalism in Turkey: Questions of Modernity and National Identity in Turkish Radio Broadcasting (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 2.

[3] I use the term Iranian art/classical music instead of mūsīqī-yi sunnatī or Iranian/Persian traditional music. The term ‘traditional’ for various negative connotations is not correct. Moreover, as I have tried to hint here, performances with instruments such as violin and piano also constituted Iranian art/classical music. In this paper, I consider pieces such as pishdarāmad, ring, and free metered vocal music known commonly as āvāz as constituting the core repertory of Iranian art/ classical music. Of course, taṣnīf or metric vocal music are potentially part of the repertory of Iranian art/classical music too. In recent years, there has been debate about the term “classical” in non-western musical contexts, including in Iran. I do not enter the ethnomusicological debates in Iran on this concept, as I think such debates have in various ways reproduced binaries and created metanarratives regarding music history in modern Iran that are ahistorical in nature. For an ethnomusicological discussion on the concepts of popular and classical in modern Iran, see Sasan Fatemi, Paydayish-i mūsīqī-i mardumʹpasand dar Irān: taʼammulī bar mafāhīm-i kilāsīk, mardumi, mardumʹpasand [The Genesis of Popular Music in Iran: Reflections on Concepts of Classical, Folk and Popular] (Tehran: Mahoor, 2013).

[4] Jane Lewisohn, based on her interviews with an influential radio authority prior to 1979, and an early sound engineer named Nikoogar, mentions that at least until the mid-1950s, the radio’s programs were performed live. Of course, there are a few sound materials available from radio performances before the mid-1950s, including a performance session from the late 1940s—recorded in the army radio on a 78rpm record—by the famous vocal musician Hoseyn Qavami and Salehi on tar. These few sound sources were ostensibly recorded on 78rpm records.

[5] Seyyed Javad Badeezadeh, Gulbāng-i miḥrāb tā bāng-i miz̤rāb: Khāṭirāt-i Javād Mīr‘alinaqī, 1281-1358 [Melody of Mihrab to the Strike of Mezrab: Memories of Seyed Javad Badeezadeh (1903-1980)], ed. Seyyed Alireza Miralinaqi (Tehran: Ney, 2004), 122.

[6] This aspect requires further detailed historical analysis.

[7] At the end of the 1940s there gradually emerges a gendered conception in the context of Iranian vocals, one that becomes prominent later in the 1950s. I have discussed this historical aspect of gender in Iranian vocal music history during the Pahlavi period in my forthcoming work. “Iranian Vocal Music and the Question of Gender During the Pahlavi Period.”

[8] For a discussion on history of music revival regarding Iranian music, see Laudan Nooshin, “Two Revivalist Moments in Iranian Classical Music,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival, ed. aroline Bithell and Juniper Hill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[9] For a discussion on Gulhā’s formation and history, see Jane Lewisohn, “Flowers of Persian Song and Music: Davud Pirniā and the Genesis of the Gulhā Programs” Journal of Persianate Studies 1 (January 2008): 79–101.

[10] See Borumand in Iḥyā-i sunnatʹhā bā rūykard-i naw [The Revival of Traditions with a New Approach], ed. Einollah Mosayyebzadeh (Tehran: Sūrih Mihr, 2014), 28.

[11] riticisms of Iranian art/classical music, as well as radio’s music dates back to 1950s and 60s. I have discussed these criticisms in my master’s thesis and have analyzed and contextualized some of the debates in a published work. See Pouya Nekouei and Reza Parvizade, “Naqd va tafsirʹhā-yi ‘ʻirfān garāyānah az mūsīqī-i Īrānī va barkhī az janbah’ha-yi bistar-i farhangi: farhangi’ijtimā‘aī mūsīqī dar dahah’hā-yi si va chihil-i shamsi” [‘Sufi-Based’ Narratives and riticisms of Iranian Music and Socio- ultural haracteristics of Musical context in 1950s and 1960s”] Pazuhisha-i Irānshināsi 10 (Winter and Spring 1400/2021): 209-224. https://jis.ut.ac.ir/article_78286. html?lang=en.

[12] For his views on shīrīn navāzī, see Majid Kiani, Haft dastgāh-i mūsīqī-i Irān [The Seven Dastgah of Iranian Music] (Tehran: Moa’llef, 1368/1181), 109-10.

[13] Fatemi, Paydāyish-i mūsīqī-i, 127.

[14] Fatemi, Paydayish-i mūsīqī-i, 127. This understanding of radio in modern Iran, in my view, owes to the Adornoian conceptualization whereby radio’s role in the promotion of commercial music, and the idea of “regression of listening” resonates prominently. For a discussion on Adorno’s “regression of listening,” see Veit Erlman, “Echoless: The Pathology of Freedom and the Crisis of Twentieth Century Listening,” in Reason and Resonance: A History of Modern Aurality (New York: Zone Books, 2019), 307-42.

[15] For a brief discussion on problems of historical writing in music, see Pouya Nekouei, “Mukhtaṣarī dar bāb muʿz̤alāt va faqar tārikh nigārī dar tarikh-i muʻasir mūsīqī-i Iran” [A Brief Note on Problems of Historical Writing in Contemporary Music History of Iran], Hunar-i Mūsīqī 182 (2021).

[16] For a comprehensive treatment of this theme in the west, see The Oxford Handbook of Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries, ed. Christian Thorau and Hansjackob Ziemer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). I have also looked at the public and private sphere and the question of listening to music in modern Iran in two separate studies. For a published discussion, see Pouya Nekouei, “Consirt va Tārikh-i Shinidan: Mardum va Mūsīqī-yi Kilāsikī dar Tehran-i Dūrah-i Riz̤ā Shāh [Concert and History of Listening: People and Iranian Classical Music in Tehran During Reza Shah’s Period],” Mardumnāmah, no. 18 and 19 (2021-2022 Fall and Winter): 10-45. https://www.magiran.com/paper/2548356/کنسرت-و-تاریخ-شنیدن.

[17] Mohammadreza Fayyaz, Tā barʹdāmidan-i gulʹha: muṭālaʻah-i jāmiʻahʹshinākhtī-i mūsīqī dar Irān az sipīdah dam-i tajaddud tā 1334 [Until the Advent of Gulhā: A Sociological Study of Music in Iran from the Dawn of Modernity until 1954] (Tehran: Sure Mehr, 2019), 163-68.

[18] Fayyaz, Tā barʹdāmidan-i gulʹhā, 154.

[19] Fayyaz Tā barʹdāmidan-i gulʹhā, 154.

[20] Fayyaz, Tā barʹdāmidan-i gulʹhā, 157-75.

[21] Fayyaz, Ta barʹdamidan-i gulʹha, 21-26.

[22] Iṭilā‘āt. “Guftār-i Rūz: Radio Tehran,” No. 4165: 1.

[23] Report addressed to “the Minister of Finance and the Chief of the Radio Commission,” National Library and Archives of Iran, Document Number 240/096320.

[24] Iṭilā‘āt-i Haftegi, July 20, 1945, 2.

[25] Tehran Muṣṣvar, August 18, 1950. No. 367.

[26] Iṭilā‘āt. June 10, 1941. “Music of Radio.”

[27] Iṭilā‘āt. March 15, 1942, No. 4835.

[28] I have borrowed this concept from Tejaswini Niranjana’s recent works. For a discussion on the concept of musicophilia, see Tejaswini Niranjana, Musicophilia in Mumbai (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

[29] Badeezadeh, Gulbang-i mihrab, 24.

[30] 30Badeezadeh, Gulbang-i mihrab, 96.

[31] “Radio Tehran’s Program,” National Library and Archives of Iran, Document Number 240/016320.

[32] National Library and Archives of Iran, Document Number, 240/096315. Until this date, the various genres of popular music in Iran had not yet completely developed.

[33] Iṭilā‘āt April 25, 1941, Friday. No. 4514, 1.

[34] The piano emerged as an important instrument of musical modernity in the context of Iranian music during Reza Shah for the performance of Iranian music. Moshir Humayun, along with Morteza Mahjubi were two prominent performers of Iranian-style piano, whose records appeared during the Reza Shah period.

[35] The brochure of Radio Tehran’s programs dated February 26, 1941. National Library and Archives of Iran, Document Number 310-065130016.

[36] “Radio’s Music Subcommittee,” National Library and Archives of Iran, Document Number 240-096315.

[37] Iṭilā‘āt.

[38] “Iranian Music”, Iṭilā‘āt, No. 4717, November 24, 1941.

[39] Document No. 91 in Documents from Music, Theater and Cinema (1925-1979), vol. 1: 267.

[40] Document No. 91: 267.

[41] For an example of schedules of Iranian music on radio during this time, see Iṭilā‘āt-i Haftigī, March 21, 1942, 23.

[42] Iṭilā‘āt, October 27, 1941.

[43] Ataollah Zahed, Document No. 06/1, in Documents from Music, Theater and Cinema in Iran, vol. 1, 274.

[44] Zahed, Document No. 06/1, 275.

[45] Zahed, Document No. 06/1, 275.

[46] For a comprehensive list, see Shahab Mena, Habib Somaei va raviyan athar-i aw [ abib Somaei and Narrators of his Works] (Tehran: Sure Mehr, 2010), 278-81.

[47] This term is commonly known as āvāz in Persian. There are of course differences of opinion about a better term for āvāz, but I do not enter musicological debates, and have used the common accepted term āvāz in this paper.

[48] Taj Isfahani, a prolific vocal musician who began his career in 1928, was invited to perform on Radio Tehran as “vocalist of Radio Tehran” from October 23, 1941. In fact, there is another document signed by Khaleqi as chief of the country’s Music Bureau, that informs Taj of his performances on the radio’s monthly programs.

[49] Performances of pīshdarāmad, vocal section, taṣnīf and ring still constitute a full cycle of classical performance.

[50] A relatively less famous, but important tar performer of Reza Shah’s period. His performances were recorded on Polyphon with red labels in Tehran at the end of 1927 and the beginning of 1928.

[51] For a detailed history of the National Association of Music, see Pouya Nekouei, “An Overview of the Activities of National Association of Music and its documents in the 1940s,” Mahoor Music Quarterly.

[52] Iṭilā‘āt 5639, November 1944.

[53] Ṣidā-yi Tehran, 1951, Personal ollection.

[54] Mena, Habib Somaei, 555. While Niknavaz was in charge of conducting this orchestra, the famous and prolific vocal musician Javad Badeezadeh was put in charge of managing it.

[55] The catalogue also mentions other orchestras: the Royal Army Orchestra, Tehran’s Theater Hall Orchestra, and the Balalaika Orchestra. The Balalaika Orchestra featured in the 78rpm records during the Reza Shah period. The orchestra performed Iranian musical pieces such as ring and pīshdarāmad but using equal temperament musical scales. Hence, I have not included it among the ensembles that performed Iranian music.

[56] Mansoor Yahaqqi in conversation with Shahab Mena, in Habib Somaei, 552.

[57] Mena, Habib Somaei, 552.

[58] Mena, Habib Somaei, 554.

[59] Iṭilā‘āt, September 19, 1949.