Trajectory of Smooth Female Spaces within the Striated Masculine in Kiarostami’s Ten

We are led to pose the woman question to history in quite elementary forms like, “Where is she? Is there any such thing as woman?” At worst, many women wonder whether they even exist. They feel they don’t exist and wonder if there has ever been a place for them. I am speaking of woman’s place, from woman’s place, if she takes (a) place.

Hélène Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation?”

In the smooth space of Zen, the arrow does not go from one point to another but is taken up at any point, to be sent to any other point, and tends to permute with the archer and the target.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Through a series of examples, in her widely-acclaimed article, “Castration or Decapitation?,” Hélène Cixous seeks to demonstrate the strictures that have been imposed on womankind throughout history. At the heart of her arguments lies the demonstration of restrictions imposed on women’s mobility that bind them to a certain turf, which is labelled as both familiar and familial. Invoking the examples of the Sleeping Beauty and Little Red Riding Hood, Cixous posits how a woman’s “trajectory is (either) from bed to bed” or “from one house to another.”[2]Although one may want to situate such restrictions in the past, the truth of the matter is that women continue to strive for their total emancipation on various fronts, not the least of which is the right towards individuation and the attainment of the status of a self-knowing subject that can only be realized if women feel entitled to unhindered mobility and an unhampered scope of action. The late Iranian director, Abbas Kiarostami has masterfully depicted the path embarked upon by a working woman in Iran, the homeland of the director and a country known for the many restrictions it imposes on women towards that actualization of the self and its concomitant aspects of discovery of the Other. The focus of this paper will be on Kiarostami’s portrayal of the nuanced trajectory adopted by Mania Akbari, who, more or less, features herself as a seemingly ambitious and active artist. As she drives through the circuitous streets of Tehran while engaging in a number of thought-provoking dialogues with a variety of passengers, primarily women, who go on to shed light on the evolving role and place of a woman in the Iranian society, the spectator appreciates how she cleverly dodges the restrictions imposed on her as she succeeds in carving out a smooth feminine space, à la Deleuze and Guattari, in the midst of the entangling striated space, which is deemed to be masculinist, restrictive and hierarchical. In addition to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s “smooth” and “striated” spaces, other theories surrounding the indispensable role of space in self-expression including Henri Lefebvre’s triadic conceptualization of space, Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notion of chiasm that entails the enfolded bond between the body and the outside world and Gaston Bachelard’s explication of what constitutes a home, spatially speaking, will come into play with the aim of situating the spatial dynamics of Ten–which marks the first time the auteur has turned women and their place in society into a pivotal theme—within the wider context of gender dynamics.

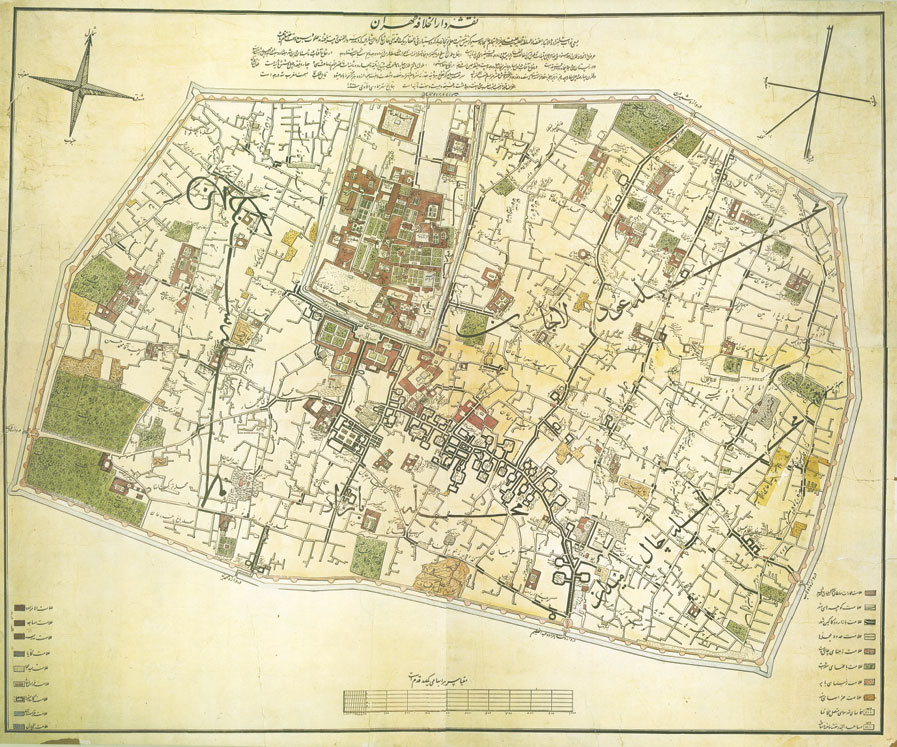

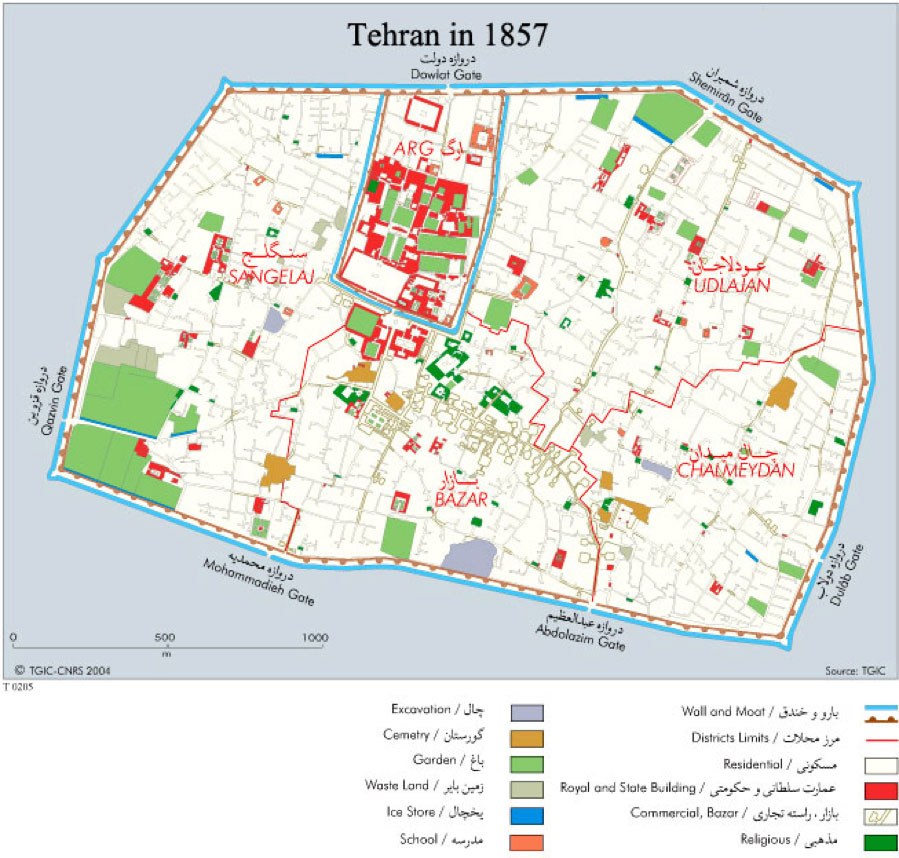

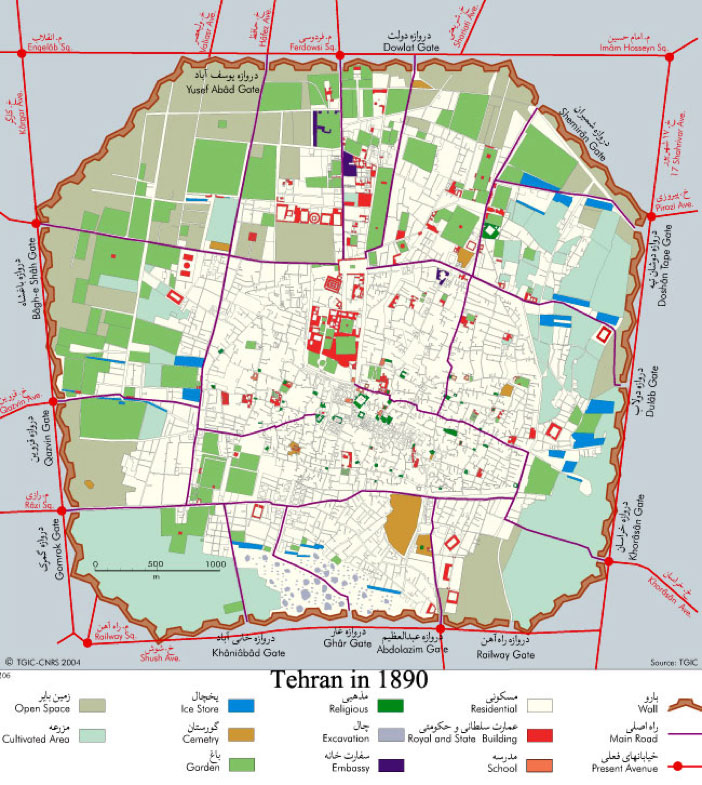

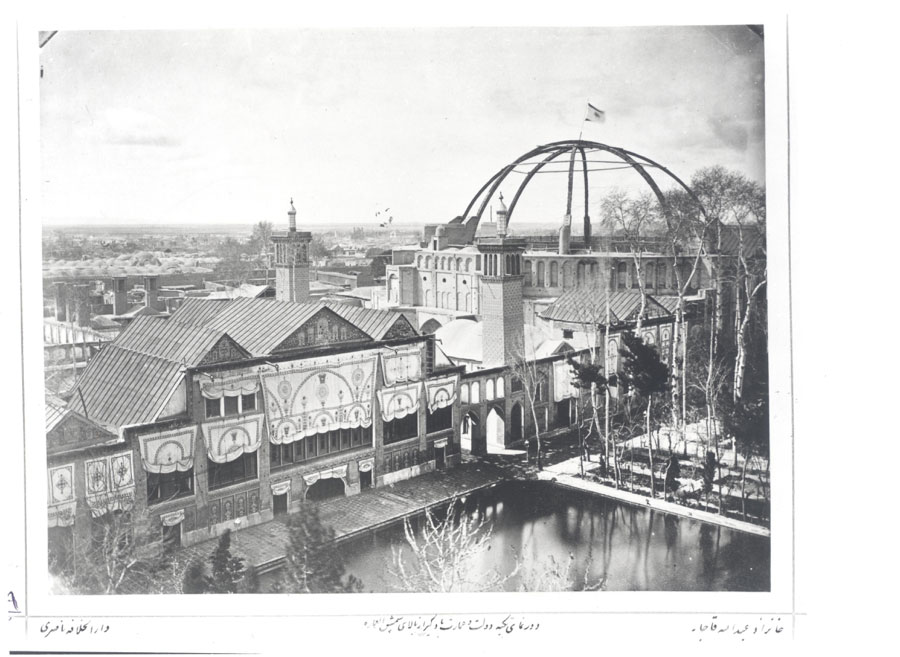

Kiarostami, skilfully portrays the unfolding of a smooth space, in the sense of its being a space that is “undirected,” “intensive rather than extensive” and “hapticrather than optical,”[3] in the midst of the striated space par excellence, that of a city. As we see throughout Ten, the female driver navigates through one of the busiest and action-ridden cities in world, during which she carves out a smooth space, which by definition, “is occupied by intensities, wind and noise, forces, and sonorous and tactile qualities”[4] in the midst of the authoritarian striated space of the city. As we see in Ten, smooth spaces, on grounds of their inherent characteristics, allow for the formation of sisterly bonds between women in the course of thought-provoking conversations that cohere around sex, heteronormative relationships, parenthood and religion, among other significant social matters (in fact, many a tabooed topic, including, abortion are also touched upon). Nicholas Balaisis is quite astute in pointing out the importance of the car in the film, as not only its primary setting, but also in terms of creating an atmosphere that inflects the conversations around driving and its corollary issues. However, despite invoking Merleau-Ponty and his concept of chiasm as the enfolded bond between our bodies and the world outside, spaces beyond the interior of the car are not the focus of argument, perhaps, for the reason that, as he posits, “in Ten, unlike A Taste of Cherry, there are no external shots of the car.”[5] That having been said, exterior spaces continuously seep into the interior space of the car, hence, the importance of analyzing certain aspects of the outside spaces, which, as shall be argued, tend to be significant for a more accurate analysis of gender dynamics.

One need not delve too much into the characteristics offered by Deleuze and Guattari regarding smooth spaces to conclude that in their evocation of sensory stimuli including touch and their overall intensity, they are very feminine in nature. The pan-corporeality that comes to the fore in the smooth feminine space is one that, though highly auditory, represents an “acoustic space,” which based on Marshall McLuhan’s interpretation, is one that is “boundless, directionless, horizonless, the dark of the mind, the world of emotion, primordial intuition, terror,”[6]as women in seemingly unscripted dialogues while meandering at times aimlessly through the striated city streets, feel a multiplicity of their senses and feelings enhanced. Balaisis rightfully invokes the gendered aspect of the interior space of the automobile when he highlights its significance as a space where “women are able to communicate freely and honestly.”[7] His observation of how the interiority of the car indicates the lack of such spaces in Iran is also worth pondering upon, although one could also see how the freedom or lack thereof that women feel within this space not only originates from but also carries over to beyond the car itself.

World renowned Swiss-French architect, Le Corbusier has described our taking up of space as the initial indication of existence (la prevue première d’existence, c’est d’occuper l’espace) which he describes as “the initial gesture of all living beings” (le geste premier des vivants);[8] yet, in order to exercise one’s basic right of freedom of speech and movement, one needs to go beyond the mere occupation of space and engage in practices that allow for an optimum use of space. Women feeling hindered even in their primary spaces, namely their homes, set about to carve out a space approximating an ideal domain for their social imaginary where they can engage in the exchange of ideas, brainstorming of alternative modes of existence and simply, an unfolding of humour or simple counter-measures in the face of the hegemonic norms prevailing outside. One could have recourse to Henri Lefebvre’s triadic conceptualization of space that boils down to space “perceived” (perçu), “conceived” (conçu) and ultimately, “lived” (vécu), “space as it might be, fully lived space”[9] to better understand the spatial dynamics that surface in the movie. It is the enactment of this “fully lived space” that one is witness to in Kiarostami’s Ten, where women of diverse class and professional backgrounds engage in dialogues with the female driver, who nudges them to reveal a bit more about themselves, their modus operandi of existence, their (philosophical) convictions and pains and miseries.

On a different level, that “fully lived space” is referred to as “spaces of representation,” which Christian Schmid interprets as the social field, “the field of projects and projections, of symbols and utopias, of the imaginaire and … the désir.”[10] The social imaginary, “the creative and symbolic dimension of the social world, the dimension through which human beings create their ways of living together and their ways of representing their collective life,”[11] comes to the fore in the course of the dialogues as Mania exchanges words on how women behave and ought to behave, for example, in the vignette on Roya, the heartbroken woman who is sobbing over her breakup: “We women are wretched creatures because when we are little we are clinging unto our mom, then unto our dad, then unto a certain man, then unto our child […].” The imagination, which manifests itself in the social imaginary here, is a power to contend with and, as anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has noted, is “no longer a mere fantasy, no longer simple escape, no longer simple elite pastime,” but it “has become an organized field of organized practices, a form of work (in the sense of both labour and culturally organized practice), and a form of negotiation between sites of agency (individuals) and globally defined fields of possibility.”[12] It is through this power of imagination that women are able to go beyond the confined spaces of the home to come up with new ways to carve out a niche where they can exchange ideas that will alleviate the pain of living in a patriarchal environment.

Gaston Bachelard’s description of a home as a place which “thrusts aside contingencies,” “without (which), man would be a dispersed being” and one that maintains one “through the storms of the heavens and through those of life,”[13] has little or no meaning in the lives of most, if not all the women depicted in Kiarostami’s Ten. This fact comes to the fore in the dialogues of Mania with her son, who reprimands her for not being at home and taking care of the household and in her dialogue with the prostitute, who highlights the discrepancies that exist between the emotional bonds between men and women within and without the home. That Mania herself appears to be constantly on the go, as pointed out by her son, Amin, whether for professional reasons or otherwise, is in and of itself an indication of the lack of security and warmth that a woman desires at home.

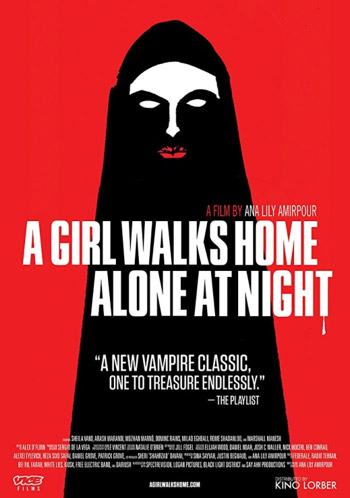

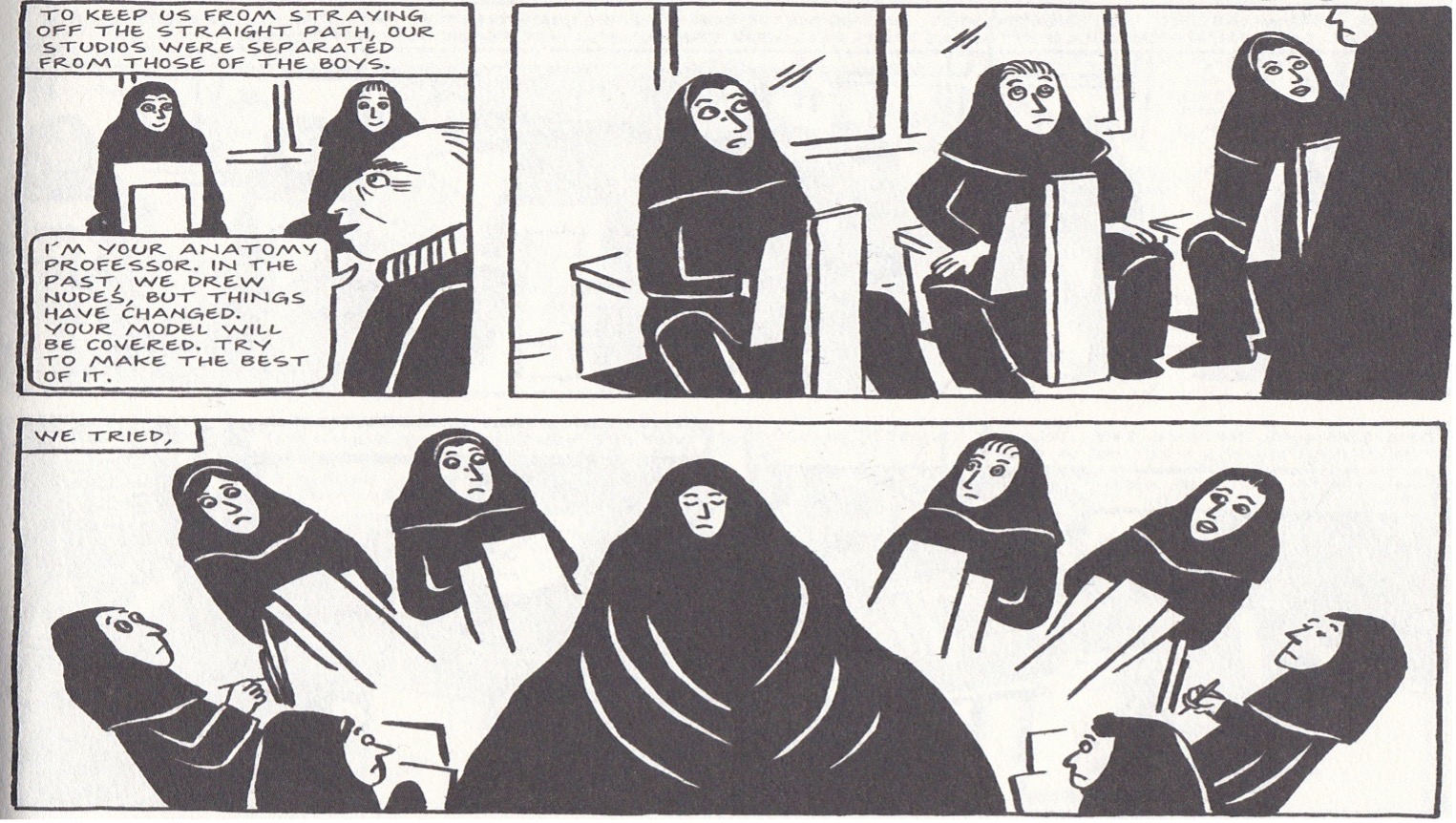

As Hélène Cixous has noted, in our patriarchal world, women should not allow themselves to venture out their homes or even beds (as we see in the classic example of The Sleeping Beauty); should not embark on the forbidden: make a little detour, travel through their own forests in the fashion of Little Red Riding Hood.[14] Similarly, what is displayed in Ten, as women travel through their so-called “own forests” created at the heart of masculinist spaces in an automobile that becomes a vehicle of (self-)investigation and knowledge/power, is quite a daring move and challenged by the so-called Symbolic Order, at the height of which lies the Name-of-the-Father that is aimed at setting down rules and regulations and putting a finale to laughter, women’s prime emblem of womanly existence that appears as a threat to the Symbolic Order as Cixous has shown us in her examples of the Medusa as well as the decapitation of laughing women in Sun Tse’s manual of strategy.[15] The smooth feminine trajectory that women are shown to embark upon, unlike the fairy-tale example of Little Red Riding Hood, is quite real as it appears to actually capture a slice of the female protagonist’s life in modern-day Tehran. Kiarostami has himself said that “I can assure you that it is all [in Ten] very true to life, and I really am giving a realistic picture of the Iranian middle-class woman as she actually is.”[16]

One of the distinguishing features of Ten is, in fact, its certain characteristics that align it with neo-realism, primarily, the use of non-professional actors that allow for the unfolding of reality as is. Kiarostami, has been aligned with Cesare Zavattini, who describes neorealism as the desire “to give human life its historical importance at every minute.”[17] Yet, as we have come to know, the genre in which Ten is embedded, though cleverly labelled as “observational documentary”[18] by Balaisis can be better termed as an example of a “new hybrid documentary form” in its “interplay between reality and fiction.”[19] Another layer of the film is remotely similar to other road films such as Thelma and Louise (1991) and Paris Texas (1984) in that, likewise, Mania is on the road, albeit with the major difference that unlike the many other examples of this genre, her trips are not goal-oriented and, even in a way, they seem to be a goal unto themselves. As Jack Kerouac has it in On the Road (1957), one has to be or be influenced by someone who is “tremendously excited with life,”[20] to hit the road; yet, in the case of Mania and her female passengers, more than being excited with life, what characterizes their movement is a sense of ontological fulfillment that finds an echo in what Spinoza calls conatus, “a striving to persevere in being,”[21] a mode of being that would grant them more space, both figuratively and literally. The myth of the mobile masculine hero, as classically represented, for example, in the figure of Oedipus, and the monstrous feminine Sphinx, who merely poses as an obstacle to be overcome as part of the heroic rites de passage, is thus reversed. What distinguishes Ten from other examples of road genres and the myth of the hero, even in its cinematic instantiations in Kiarostami’s own oeuvre, is that this time round women dominate the scene.

Joan Copjec, has rightfully, pointed out “the accusation persistently levied against [Kiarostami’s] cinema was that it was wholly indifferent to the condition of women in contemporary Iran and sought, rather, to catch the eye of Western audiences by serving up the kinds of Orientalist images they expected to see: male protagonists driving through a timeless, rural Iran dominated by the ubiquitous presence of other men, with women shunted to the margins, hidden behind doors or toiling in long shot on the fringes of vision.”[22] What comes to the fore in Ten, is a reversal of gender roles in the trajectory that is traced out in the film, as we see a woman at the wheel interacting with other women, with the exception of her son. In addition to the feminine aspects of the trajectory, one ought to refer to similar aspects of the interiority of the car, which bring about an inescapable sense of intimacy that allows for raw exchanges that lead to eye-opening confessions.[23] Many a time, we see how Mania, subtly engages in the art of extracting those truths from her passengers and along the way, so as to get to the heart of the inner recesses of their minds, their unconscious. The film is rife with such instantiations as they come to the fore in the dialogue with, for example, the prostitute, who initially, refrains from opening up, but then being nudged by Mania on multiple occasions to respond to the question of “why, she being so young, engages in the profession that she does,” she relents and takes a stance in defense of her choice in a seemingly nonchalant manner that nonetheless hints at the many repressions that have taken place within the unconscious. For example, she does confess to having at least once been in love, but then goes on to stress the dishonesty of men who tell their wives that they love them while spending time with the likes of her.

In addition to the mobile aspects of the trajectory, the means of the journey, an automobile, is one of significance as Kiarostami himself notes in 10 on Ten. For a fact, the car in its mobility affords hope to the women appearing in Mania’s vehicle whose destinies seem to be sealed by a socio-political system that has failed them at every turn of the road. Kiarostami says how the idea of the film came to him once he heard about a female psychiatrist whose office had been closed in the wake of a complaint by a female patient who had come to regret a decision to separate from her husband in the wake of consultations with the psychiatrist. As a result, the psychiatrist decided to turn her car into a mobile office.[24] When looking at the dynamics going on in Ten, at times, Mania serves as a psychiatrist by nudging her passengers to speak out their mind. For example, in her dialogue with the prostitute, which happens to be modeled on information that Kiarostami had garnered through telephone conversations with actual prostitutes and not on any data provided by a real prostitute as no prostitute was willing to act the role, one sees Mania using subtle tactics to extract some personal information within the context of love, sex and relationships. However, the significance of the closed space of the car is definitely worth taking into account as it, for the most part, compels the passenger to sit still and give into the process of conversation/therapy and eventually, perhaps, confession. That the primary spatial focus, unlike Taste of Cherry, is on the inside of the car rather than the outside, enhances the atmospheric intimacy between the characters and allows for the surfacing of some sort of sisterhood between the women who partake in the ride.

Going back to Deleuze and Guattari’s explication of smooth spaces and their characterization as haptic, which they describe as being “a better word than ‘tactile’ since it does not establish an opposition between two sense organs but rather invites the assumption that the eye itself may fulfill this nonoptical function,”[25] one can better appreciate the choice of the interior of an SUV for the conversations that constitute the basis of the movie in that they lend themselves to the emergence of such feminine and intimate spaces. Significantly, smooth spaces and their haptic characteristics have mostly been aligned with the nomadic life, which is associated with being local and not global, in the sense that “there is close vision, space is not visual, or rather the eye itself has a haptic, nonoptical function: no line separates earth from sky, which are of the same substance; there is neither horizon nor background nor perspective nor limit nor outline or form nor centre.”[26] The description of the local aspect of nomadic space characterizes it as non-hierarchical and borderless which fits in with the ambience that the moving car creates in ways that allow for stories to play out by themselves without direct directorial intervention. To better understand the differentiation of “smooth” and “striated” spaces, Deleuze and Guattari present the image of the painter’s involvement with the painting: when the artist takes a step back, s/he is developing a “striated” perspective; on the other hand, when the painter happens to be so close that s/he gets lost in the strokes, s/he is within “smooth” spaces, so to speak.[27]

A stanza by Rumi much cited by Kiarostami, including in 10 on Ten, which can be translated as “You are my polo ball and you ran before my mallet and I run after you although I made you run,” explains an element in the maestro’s work that comes to the fore in Ten, amongst his other films. That element is one that from a sub specie aeternitatis view can fall between free will and determinism, in that, it simultaneously manifests the enforcement of directorial dictates and the emergence of unscripted scenes as those which come to the fore in Ten. The installation of two digital cameras on the dashboard, to whose existence nonprofessional actors tend to be oblivious, in fact, allows for the emergence of a comfortable ambience that aligns itself with that of “smooth spaces,” in its characteristic element of intimacy, in that, while actors seemingly go by a certain diegetic template, they end up coming up with their own add-on scenarios further bringing home the importance of the mystic maxim of Rumi’s verse, as cited above, in the creation of Ten. Alain Bergala, in his categorization of the car device (le voiture dispositif) in his commentary on Kiarostami’s cinematic corpus, attributes its roles as “an apparatus to encounter the real” (une machine à rencontrer du reel) and “a pleasant space for a conversation between two people” (le bon espace à parler à deux) to the vehicle used in Ten. In expanding upon the former attribute, Bergala highlights the role of the car as a vehicle which enables encounters, both organized and random, and as such, Kiarostami finds himself exempt from the burden of setting up scenarios: “through the car door, at any moment, one can find a face, a body, a personage, a slice of reality come to the fore.”[28] This aleatory aspect of the film that emerges as a result of the choices made in terms of space and setting, speaks to the verse by Rumi in that it manifests the director’s predilection for setting the scene in ways that allow for that unpredictability that will in turn galvanize him into movement, bearing in mind that it was he in the first place, who set the ball into motion.

Going back to the other aspect brought up by Bergala with regard to the dynamics of the car in Ten, namely, that it is conducive to giving rise to tête-à-tête conversations, one can see how this aspect could be more prominent when two women were involved in dialogue. Women, more so than men, tend to view themselves as part of a gender-based collective and as a result sympathize, empathize and commiserate more easily with other women being fully conscious of the challenges that tend to beset them more so than men in a predominantly patriarchal world. American feminist scholar, Nancy Chodorow makes the following observation: “Girls come to experience themselves as less differentiated than boys, as more continuous with and related to the external object-world and as differently oriented to their inner object-world.”[29] As Susan Stanford Freedman has noted, “by ‘object’ Chodorow does not mean ‘things,’ but rather people.[30] Chodorow continues to highlight the significance of the feminine paradigm which situates itself in a collective unlike the masculinist approach: “Women’s object-world’ remains a more complex relational constellation than men’s … Masculine personality, then, comes to be defined more in terms of denial of relation and connection (and denial of femininity), whereas feminine personality comes to include a fundamental definition of self in relationship.”[31] Taking these factors into account is significant for a better appreciation of the intimate conversations that unfold in the course of Ten, some of which, as mentioned earlier, segue into confessions that enfold the very essence of womanhood. Perhaps, one of the most memorable of these conversations is the one that takes place towards the end between Mania and a heartbroken and disillusioned Katayoun who has taken to prayers in her lovelorn state, a move which she had not found herself previously capable of. Significantly, the fact that she has shorn herself of her hair, in a country whose most visible emblem of religiosity is the enforced donning of hijab by women, intimates a new beginning to a self that is attempting to recover from the ashes of a lost love. Phoenix-like she may not be; however, doffing the headscarf to expose a shaven head in a country like Iran is indicative of a form of resistance that may lead her towards a new path that entails more self-reliance and self-discovery.

One of the primary results of becoming aware of one’s self and consciousness is the emergence of an independent subject in the modern world. Most of the women depicted in Ten (with the exception of the older religious lady) are on the path towards attaining the status associated with a self-knowing subject which is one of the hallmarks of modernity.[32] However, in order for that conscious subject to emerge, certain factors have to be in place including a safe space through which the subject can explore the self and her surroundings and, as famously noted by Virginia Woolf, “a room of one’s own,” which denotes a space where the subject can sit still and contemplate on the self and its inner transformations. The dialogues that play out in the course of Ten during the meanderings of the self-seeking and inquisitive protagonist of the film, hint at a collective engagement in the act of self-knowledge, which, as Teresa de Lauretis brings to the fore in her arguments on the ramifications of the Oedipus myth, is at the heart of each heroic myth. That quest, as noted by de Lauretis, includes hurdle(s) that not only mark spatial boundaries, but also lead to questions that target the ontological essence of (wo)man.[33] While, as already discussed in the paper, the nature of the spaces which the women carve out in the course of their navigations across the congested streets of Tehran, comes close to Deleuze and Guattari’s description of “smooth spaces,” these spaces exist in tandem with other spaces, described as “striated” that pose as literal or figurative bumps on the path of the women in the film. Examples surface in the course of the journey such as the first vignette with Katayoun in which Mania picks her up from the Ali Akbari Mausoleum and is confronted by a male driver who is blocking her way and goes on to falsely accuse her of driving in the wrong direction. While the city in and of itself is an example of a “striated space” par excellence with its too many institutions and embedded regulations; yet, these so-called nomadic women, though destitute of the proverbial “room of one’s own,” are shown to take matters into their hands by breezing through one of the most populated cities in the world to gain a measure of freedom and agency towards self-realization.

This nomadic aspect of the women, which also happens to accord with the characteristics of “smooth spaces,” gives them not only a certain level of scope in the construction of a social imaginary of sisterhood, but also allows for the emergence of a circular space that is feminine in nature and contrasts with masculine, linear, logocentric goal-oriented movements. Deleuze and Guattari posit that “the nomads have no history; they only have a geography”[34] and then go on to suggest how the nomads can gain the upper hand through capturing the “force of the hunted animal” so to speak, meaning that the nomads, instead of acting like the hunter whose “aim was to arrest the movement of wild animality through systematic slaughter, […] [set about] conserving it, and, by means of training, the rider joins with this movement, orienting it and provoking its acceleration.”[35] The women are engaged in becoming, which, as maintained by Deleuze and Guattari, “has no term, since its term in turn exists only as taken up in another becoming of which it is the subject, and which coexists, forms a block, with the first.”[36] As a result, they are full of a dynamism that allows them to defamiliarize the familiar and thus look at their surroundings and themselves through nuanced perspectives. The nomadic women depicted in Ten, far from reversing the hunter-hunted vector in the battle of the sexes, go beyond paradigms of war and hunting with the aim of harnessing the power of masculinity so as to re-orient it in ways that will lead to a partial reclamation of their rights, a reterritorialization of their spaces. Never do we see these women attempting to arrest the masculinist forces in place as we observe how they harness patriarchal forces as they weave their way through the smooth grooves existing in the heavily striated phallocentric texture of society. One need only observe Mania’s attitude towards her husband and son and her cleverly navigations across the striated space par excellence: the polis (in this case, Tehran), to appreciate examples of such a nomadic approach. Creatures of cartography they are without looking behind or ahead in tandem with the nomadic characteristics that they embody and they move within their terrain with no specific goal other than becoming in sight. The perspective that they incarnate resonates well with that of a number of Kiarostami’s early works including Bread and Alley (1970) and Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) which showcase the contingencies that accompany a goal-oriented trajectory, in its lack of a specific goal or destination and allows for the surfacing of aleatory elements that are part and parcel of human existence. This simultaneously serpentine and serendipitous characteristic of the spaces accords with the film’s form in its use of two DV cameras on the dashboard which come close to eliminating directorial mediation.

Film scholar, Ohad Landesman has made a series of interesting comments on the “unclassifiable hybrid”[37] aspect embodied in Ten that comes to the fore as a result of the use of DV cameras rendering it an artistic example of a cinematic oeuvre which lies along the interface of the factual and the fictional and he also highlights the democratization that is realized in the process. Nonetheless, I am not quite sure if one could classify the ambience that surfaces in the car as “voyeuristic,”[38] as the connotations associated with that term tend to more often than not sexual. Elsewhere, Landesman characterizes the interior space of the car as “claustrophobic,”[39] which may not quite be the case in that most spectators take into account the surrounding urban spaces in their viewing of the film. The striated aspects of the metropolis make themselves palpable through the occasional honking and, as already mentioned, the masculinist voice that, in seeing a woman at the wheel, wants to assert itself in accusing the woman of not driving the proper way; yet, overall, aside from the punctuated presence of those spaces within the interiority of the car, the spectator becomes privy to a series of preoccupations on the minds of these women ranging from their desire for that ever-elusive matrimonial bliss to their will to resolving their miseries through perpetual prayers. There is an allure and appeal in the act of discovery that the spectator partakes in alongside Mania; however, I am not quite sure if that aspect per se could be qualified as “voyeuristic,” unless one were to assume a very diluted connotation of this simultaneously cinematically and sexually charged term.

As much as one were to commend the agency that the women depicted in Ten have garnered, it would be a far stretch to attribute to them the possibility of the blossoming of a fully self-knowing and empowered subject for a variety of reasons. It is true that these women have moved beyond the “bed to bed” and “one house to another” trajectory that Cixous has bemoaned and have expanded their scope of action beyond that of Phyllis Wheatley, who, according to Alice Walker, was “a slave who owned not even herself;”[40] however, they have yet to move to that level of personhood that renders them free to roam around outside confined spaces and that of someone who has a home and not merely a house to go to. These women are on their way to enacting their rights to exercise their social imaginary in a fully-lived (vécu) space and seem to be getting close to creating a niche that will go beyond smooth spaces towards the formation of an actual safe and sound space that can be called home. What transpires in the course of Ten, is a feminist attempt at the recognition of the self and Other in a discursive on-the-go space that embraces a multiplicity of discourses including the right for self-expression, the freedom of movement, the right to dress as one wishes and ultimately, the right to move in the direction of individuation without feeling hampered by obstacles embedded in a predominantly masculinist attitude that for centuries have come to view women as the realm of the propre (both as an object of ownership and a subject that has maintain cleanliness and rectitude).[41] Going back to the citation from Cixous which appears at the very beginning of the paper, the women that appear in Ten are fully conscious of their existence to the point that they are assiduously engaged in their ontological fulfillment and realization; yet, their quest seems to be for a niche where they can exercise their rights without having to fear the patriarchal forces outside. These women, unlike the women whom Cixous is referring to, are aware that they, indeed, have a place and what we see unfold in the course of the movie is their proactive attempts at creating smooth spaces that will, ultimately, peacefully co-exist with exterior striated spaces in ways that will, in the end, lead towards an oasis which they can almost call home.

[1] Pouneh Saeedi is a sessional lecturer at the University of Toronto where she has been teaching Gender and Media Studies for a number of years. Amongst her previous publications mention can be made of “Female Figurations in Kiarostami’s The Wind Will Carry Us (Canadian Journal of Film Studies, 2013) and “Women as Epic Sites/Sights and Traces in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” (Women’s Studies, 2015). A shorter version of her current paper was presented at the Canadian Humanities Congress held at the University of Victoria in 2013.

[2]See Hélène Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation?,” Signs 7, no. 1 (1981): 43.

[3]Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 479.

[4]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 479.

[5]Nichalos Balaisis, “Driving Affect: The Car and Kiarostami’s Ten,” Public: Art, Culture, Ideas (2005): 72,

public.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/public/article/view/30063/27626.

[6]Marshall McLuhan, “Five Sovereign Fingers Taxed the Breath,” eds. Edmund Carpenter and Marshall McLuhan, in Explorations in Communication: An Anthology (Boston: Beacon Press, 1960), 207.

[7]Balaisis, “Driving Affect,” 74.

[8]Le Corbusier, “L’espace Indicible,” Le Corbusier, Savina, Dessins et Sculptures, éd. Sers (Paris, 1984), 1.

[9]Rob Shields, Lefebvre, Love and Struggle: Spatial Dialectics (London: Routledge, 1996), 160.

[10]Christian Schmid, Stadt, Raum und Gesellschaft: Henri Lefebvre und die Theorie der Production des Raumes (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2005), 205.

[11]John B. Thompson, Studies in the Theory of Ideology (Cambridge: Polity, 1984), 6.

[12]Arjun Appadurai, Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 31.

[13]Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 7.

[14]Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation?”, 44.

[15]Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation?”, 42; Cixous, “Laugh of the Medusa,” Signs (1976): 885.

[16]See Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami, trans. Belinda Coombes (London: Saqi in association with Iranian Heritage Foundation, 2005), 176.

[17]See Craig Fisher, “Comics and Film,” in The Routledge Companion to Comics, eds. Frank Bramlett, Roy T. Cook, Aaron Meskin (New York: Routledge, 2017), 344.

[18]Balaisis, “Driving Affect,” 72.

[19]Ohad Landesman, “In and Out of this World: Digital Video and the Aesthetics of Realism in the New Hybrid Documentary,” Studies in Documentary Film 2, Issue 1 (2008): 33.

[20]Jack Kerouac, On the Road (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 4.

[21]Steven Nadler, “Baruch Spinoza,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Calif: Stanford University, 2016) ,plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2016/entries/spinoza/.

[22]Joan Copjec, “Cinema as Thought Experiment: On Movement and Movements,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies27, no. 1 (2016): 150.

[23]Michel Foucault makes a distinction between ars erotica and ars sexualis. He situates the former in the East and the latter in the West. Foucault distinguishes the former in being esoteric and operating on the basis of “knowledge that must remain secret” and the latter, he aligns with “procedures for telling the truth of sex which are geared to a form of knowledge-power strictly opposed to the art of initiations and the masterful secret: I have in mind the confession.” However, what we observe being played out in terms of the confessions that come to the fore in Ten seems to be more in tune with the ars sexualis in terms of confessions serving as a means to the unfolding of the truth as is, particularly, evident in the dialogue between Mania and the prostitute and not so much the ars erotica that was dominant in the East in ancient times. See: Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 57–58.

[24]Abbas Kiarostami, 10 on Ten, DVD, directed by Abbas Kiarostami (2004; New York: MK2/Zeitgeist Films).

[25]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 492.

[26]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 494.

[27]Here, Deleuze and Guattari cite Cézanne as an example who spoke of “the need to no longer see the wheat field, to be too close to it, to lose oneself without landmarks in smooth space.” Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 493.

[28]Alain Bergala, Abbas Kiarostami (Paris: Cahiers du cinema: SCÉRÉN-CNDP, 2004), 77.

[29]Nancy Chodorow, Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 167.

[30]Susan Stanford Friedman, “Women’s Autobiographical Selves,” in The Private Self: Theory and Practice of Women’s Autobiographical Writings, ed. Shari Benstock (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 41.

[31]Chodorow, Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender, 169.

[32]See Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture (New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 94–95.

[33]As noted by De Lauretis, female spectators mostly see themselves aligned with “the mythical obstacle, monster or landscape,” thereby rendering it difficult for them to entertain themselves as subjects. Kiarostami has therefore applied an interesting narratological twist here in granting women agency against hurdles that could be interpreted more so in light of the masculine than the feminine. See De Lauretis, Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 141.

[34]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 393.

[35]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 396.

[36]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 238.

[37]Landesman, “In and Out of this World,” 38.

[38]Landesman, “In and Out of this World,” 38.

[39]Landesman, “In and Out of this World,” 36.

[40]Alice Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” in Worlds of Difference: Inequality in the Aging Experience, eds. Eleanor Palo Stoller and Rose Campbell Gibson (Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press, 2000), 50.

[41]As Betsy Wing says: “Since woman must care for bodily needs and instill the cultural values of cleanliness and propriety, she is deeply involved in what is proper, yet she is always somewhat suspect, never quite propre herself.” See Betsy Wing, “Glossary,” in The Newly Born Woman by Hélène Cixous and Catherine Clément, trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 167.