Voluntary Conversions of Iranian Jews in the Nineteenth Century

Nahid Pirnazar <nahidpirnazar@gmail.com> earned her Ph.D. from UCLA in Iranian Studies, teaching the Habib Levy Visiting Professorship of Judeo-Persian Literature and The History of Iranian Jews at UCLA. Dr. Nahid Pirnazar is the founder and president of the academic research organization, “House of Judeo-Persian Manuscripts.” Dr. Pirnazar’s works have been featured in English and Persian in Academic publications including, Irano-Judaica, Irānshenāsi, Iran Nameh and Iran Namag. She is also a contributor to the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World as well as Encyclopedia Iranica and the guest editor of the quarterly of Iran Namag (Summer, 2016).

Prior to the nineteenth century, with few exceptions, voluntary conversion was an unknown phenomenon in Iranian Jewish history. In Islamic Iran, infrequent voluntary

conversions were mainly for socio-economic or cultural reasons. According to the Shi’ite interpretation of Koranic Sura IX, verse 28, Jews were characterized as “impure and non-beleivers.”[1] In this respect, Ephraim Neumark, a visitor from the Holy Land in late 19th century, reported: “In Iran, they do not purchase bread or other food stuffs from Jews, and should a Jewish to purchase from a Muslim, he must point to the product he wishes to purchase from a distance.[2]

Furthermore, dominated as “ahl al-Dhimma” meaning “under the protection of Islam,” Jews were prohibited from celebrating their identity. Thus, at the threshold of the nineteenth century, the deprived, humiliated, and hopeless members of the Iranian Jewish community—with the exception of a few educated and elite members—were left without self-esteem, dignity and pride, almost fading away from the consciousness of Western Jewry. Iranian Judaic traditions were outdated, as religious laws had remained untouched since Joseph Caro’s fifteenth century halakhic book, Shulhan Arukh, a guideline for Judaic traditions and laws.[3]

History has demonstrated that, while disasters and hardships may strengthen one’s religious ties, they may also draw an individual either to denial of faith or the search for a spiritual alternative. Mohammad Saeed Sarmad Kashani, a seventeenth century poet of Jewish descent, is an example of the latter, as he sought a spiritual alternative to voluntary conversion. He turned from Judaism to Islam, Hinduism, and mysticism, respectively, before ultimately being beheaded as an agnostic on the steps of Jame‘ Mosque in Delhi around 1661. Similar cases are noted the discourse of “Jewish Sooffees of Meshed and Bokhara in 1831,” as reported by Joseph Wolff, a Christian missionary, and the experience of the Jews of Kurdestan, who celebrated the Jewish festival of Simchat Torahwith Soofi type mystic dances of samā‘.[4] Upon review of the motives above, one can infer that the urge for religious conversion, as a solution, often speaks of a profound need for social change.

Image of Iranian Jews in the Nineteenth Century

Unlike some of the governing bodies in neighboring countries, the Qajar rulers (1779-1924) denied the Jews important economic roles. In addition to occupying low-income professions, Jews were nonetheless able to participate in businesses prohibited to Muslims.

Only in a few major cities did Jews have the opportunity to occupy higher social positions outside of the Jewish community, mainly as physicians for the royalty or for the public.[5] Reports from travelers and Christian missionaries such as Joseph Wolff, Henry Stern and other travelers including Benjamin II, who had visited Iran at the time, talk about the friendly attitude of royalty to such doctors; otherwise, the inferior social conditions of Iranian Jewry remained largely unnoticed through the first half of the nineteenth century. It was not until the famine in 1871 and the two visits of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar ( 1848-1896) to Europe, in the years 1873 and 1889, that the attention of European Jews was drawn toward the Jews of Persia.[6]

At the time, the insecure social environment and weak legal system of the Qajars had allowed an alternative protective measure, the Capitulation Law, to be used by some affluent families including elite Jewish ones.[7] Those holding dual nationality were sheltered under the protection of their respective new countries’ jurisdiction.[8] While some Jews sent petitions pleading their legal and social cases to European Jewish organizations such as the Anglo-Jewish Association or the Alliance Israélite Universelle, most Jews did not have such access.[9] Under such circumstances, for unprivileged and unprotected Jews, change of faith offered an alternative, or even a remedy to improve or gain legal and social respect. Persian Jews waited for the arrival of Alliance schools as an expected liberator who would offer them education, protection, and self-esteem. Mr. Bassan, the Alliance representative to Kermanshah in 1904, described his arrival in the city by reporting that, “For the Muslims, I was a strange creature; for my fellow Jews, a person to be treated with the greatest respect and who had come to bring security and tranquility.” The memoirs and documents reflected in the bulletin of Alliance give testament to the community’s lack of self-esteem, pride, and security. Albert Confino, the first educator sent to Iran, reports the enthusiasm, emotions and the tears he received upon his arrival to Kashan and later Isfahan, “as if they were welcoming not the teachers or founders of school, but liberators in person”.[10]

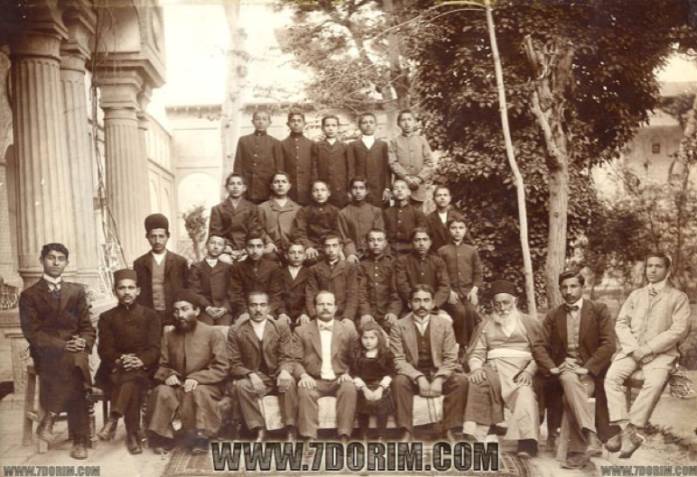

Alliance Israélite Universelle, faculty and students,15th year anniversary of the boys school in Tehran Courtesty of www.7dorim.com

Alliance Israélite Universelle, girls’ school Kermanshah, 1950.

Iranian Jewish emancipation was facilitated as a result of the education provided by Alliance, the first school established in 1898, the limited civil rights provided by the constitution for all minorities in 1906, and the revival of the dream of Zionism, thanks to the Balfour Declaration, signed in 1917. Such privileges not only established a “national identity” for Jews, but also transformed the means for the fulfillment of respected social status and a gradual change to their social reputation and the rate of religious conversions of Iranian Jews.[11]

At this point, unlike the Sephardic Moranos of Spain, a number of the forced converts of Jews of Mashhad, named as Allah Dad (God Given) or Jadid al-Islam (New Muslims) returned to their original faith.

Conversion to Islam

In the unstable atmosphere of the nineteenth century, Jewish voluntary conversion to Islam, for the most affluent families, was stimulated by socio-economic or professional reasons. Prestigious positions such as private physician to the royal family—individuals like Hakim Haq Nazar and Hakim Nurmahmood, servicing the Qajars—or instances of intermarriage between prominent members of the two communities were the causes behind some conversions.[12] As for common people, the stigma of “impurity,” as well as mandatory observation of Jewish religious and legal restrictions were strong motives.[13] In that period of instability, financial and social issues were serious impetuses for conversion to Islam. Among the motivations for conversion to Islam were financial issues depriving Jews of legal and business rights for making transactions with Muslims. The Law of Apostasy allowed Muslim members of the family be the sole recipients of the family inheritance; among other incentives for conversion were exclusion from the larger Muslim community, obligation to wear certain attire and identification patches, and lack of protection by the authorities even toward physicians serving the royalty or the public in case of malpractice.[14]

A number of prosperous families adopted Islamic identities, at least by pretense, mainly duetothe restrictions imposed by laws of impurity which helped Jewish individuals avoid segregation, and to be allowed to establish social ties with Muslim neighbors and business partners. Aside from the very few cases of Capitulation Law, nominal conversions to Islam were employed as a legal strategy to protect the economic interests of privileged families. This practice was tolerated by both the Shi’a ‘ulama and the Jewish community, without incurring the usual demands from converts to publicly observe Islamic edicts such as mosque attendance.[15] Despite these alleged nominal, or covert conversions, such families, like that of Hakim Nurmahmood maintained their prominence in the Jewish community. In later years, some of their descendants such as Dr. Loghman Nehoray even served as Jewish representatives in the National Assembly without the potential stigma of covert conversion.[16]

Hakim Nurmahmood received patients at his home in 1880s

Courtesy Amnon Netzer, Padyavand III, 1999.

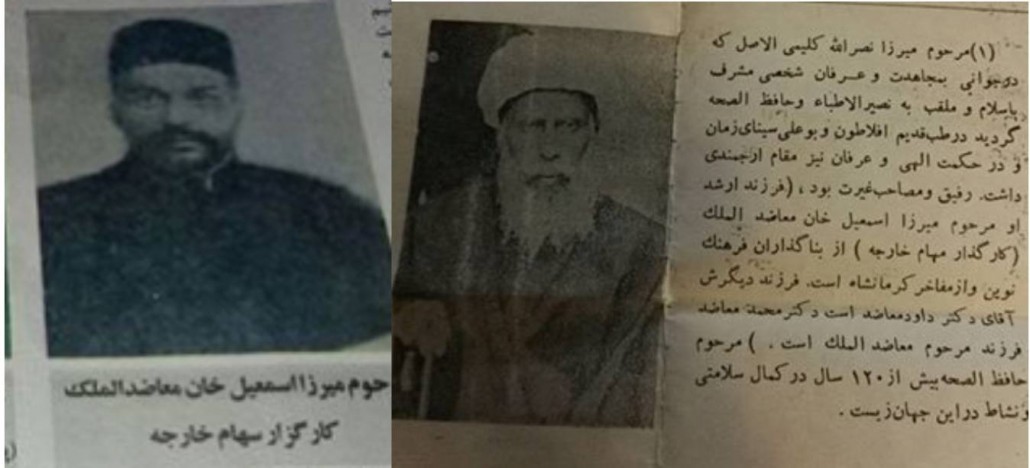

In other cases, however, publicly known conversions were mandatory. One such case occurred in the western city of Kermanshah in the late nineteenth century, when the daughter of a Muslim cleric fell in love with Isma‘il, the son of a prominent Jewish physician, Hakim Nassir. In in order to save the family’s honor, not only did the young man have to marry the daughter of the cleric, but also seventy of his family members were obligated to publicly convert to Islam. Later, in the post-constitution era, the newly converted groom, who was given the title of Mo‘azed al-Molk, (deputy administration) became the vice president of National Assembly in Tehran, and eventually the deputy Finance Minister in the national cabinet. Many descendants of the family, following the will of the Hakim Nassir, returned to Judaism once the political conditions allowed or when they migrated abroad.[17]

Hakim Nasir family from Kermanshah and his son Mo‘azed al-Molk years after conversion into Islam

Courtesy of Nina Harouni Springer (2017). See: Avraham Cohen, “The Jewish Community of Kermanshah (Iran) from the early 19th century to the Second World War,” Jerusalem 1992 (Heb) rights & permission: Noam Publishing, Jerusalem.

Courtesy of Mo‘azed family reporting about the Jewish heritage of

Nasir al-atebba’ and Mo‘azed al-Molk (2017)

For commoners, voluntary conversion had a dual cost. They had to cut ties with the Jewish community, while in the Muslim community, they still continued to bear the stigma of outsiders, carrying the name Jadid al–Islam (new convert). Such derogatory connotations haunted following generations as well, whereas conversion to other minority faiths did not carry any later tag.

Conversion to Christianity

Historically the Jews have lived in Iran about 900 years longer than Christians.[18] Nevertheless, all religious minorities in Iran, including Christians, Assyrians, Nestorians and Armenians, had not much conflict with the Jews, as all more or less shared the same experience in Islamic Iran.[19] However, beginning with the 19th century, various Christian outreach societies such as the London Missionary Society from England and the American Presbyterian Missionary from America undertook a vast policy of spreading Christianity among not only the Nestorian Assyrians in Northern Iran, but also among the Jewish communities throughout Iran and Central Asia. Although missionary activities were permitted for the purposes of attracting non-Muslims, the protocol was not always observed by the missionaries in their effort to convert some Muslims.[20]

For the Jews of Iran, conversion to Christianity was another means of escaping their living conditions. Though they were not very successful at first, the seeds of their work blossomed among the Jews through the latter part of the century. Ironically while leaders of European Jewry were negotiating with Nasser al-Din Shah regarding the establishment of Alliance schools, during his two trips to Europe, Western Christian missionaries had acted more swiftly and were already trying to promote their faith by offering hygiene, medical, and financial facilities in Iran. [21]

Among the many British evangelical missionaries to Iran in the early nineteenth century, Joseph Wolff and Henry Stern are particularly valuable historical resources thanks to their descriptions of Persian Jewish society.[22] Joseph Wolff (1795-1862), throughout his life made three missionary journeys to Iran.[23] His first journey (1821-1824) described in Missionary Journal and Memoirs of Revered Joseph Wolff; his second journey (1831-1834) was recorded in Researches and Missionary Labours Among the Jews, Mohammedans, and other Sects; and his third trip was reported in Narrative of a Mission to Bukhara to Ascertain the Fate of Colonel Stoddart and Captain Conolly.[24]

Joseph Wolff, on his three different trips to Iran reports on his numerous visits with the crown prince Abbass Mirza,[25] and speaks about the religious identity of the Jews of Mashhad even before the massacre of 1839. According to Wolff, by 1831 and before the Massacre of Mashhad, some Jews of Mashhad had dual religious identity, mainly for business and social reasons. Wolff describes “Mullah Levi Ben Meshiakh, a Mohammedan at Meshad, and a Jew whenever he goes to Sarakhs, while his wife and children still professing Jewish religion.”[26] He also describes the level of cultural assimilation of the Jews, finding them writing Hafez in Judeo-Persian, while not having many religious books such as the Talmud available.[27] He even writes about Jewish Suffees studying the Quran, led by a Muslim Morshed named Mohammad Ali, with the aim of finding confirmation of the validity of their Suffee systems.[28] As an evangelist, Wolff expresses his regret for seeing that “no attempt has ever been made in the way of converting these Jews,…who are ignorant on the subject of Christianity.”[29] Furthermore, it is in his book, Narrative on a Mission, that he speaks of the converts of Mashhad of 1839, referring to them as “Islam Jadeeda.”[30]

Henry Stern was another evangelical missionary who visited Iran twice in 1844 and 1852.[31] On his first trip in 1844, he traveled through Damascus and Baghdad. In Iran he first visited Kermanshah, and Hamadan, both in western Iran and later Shiraz in the south then going north towards Isfahan, with Tehran as his final destination. It is during this visit in Tehran that he most likely met with the Physicians of the Court of Mohammad Shah (1834-1848), including Ḥakim Ḥaqnaẓar and Ḥakim Moshe and their sons, the latter converts to Christianity. Stern indicated that the main outcome of this period was the creation of interest in the study of the books of the Christian Society and the eagerness to enter into discussion on the subject of Christianity.[32] One possible result of this connection is the later conversion of Mirza Nurollah, the son of Hakim Moshe.

On his second trip in 1852, which Stern reports in Dawnings of Light In the East, Stern considered traveling in Iran as perilous. On both trips Stern portrayed the misery and poverty of Jewish communities, blaming the Church for being so late and “unmindful of her duty and indifferent to the call of thousands of Jews, calling for help.”[33] He reported that, during his visit to Kermanshah, on a Shabbat morning dated Febuary 27, 1852, upon his entrance to a local synagogue in “an unhealthy part of the town, and amidst a few wretched hovels, which [were] striking proof of the misery of their occupants,” he is kindly received by a mulla [rabbi]. On his entrance, he is offered “an unoccupied seat on a mat,” and a talis, the prayer shall, which he politely refuses to wear, responding “ I did not require such implements in pouring out my feeling in prayer to God.” Upon the conclusion of the service which he finds “neither solemn nor devotional,” he is invited to the oratory, preaching to them of “the very Savior whom they ignorantly have so long despised and rejected,” attributing all the misery and suffering of the community to the sin of not having yet accepted Christ as the Savior. He further adds that:

One of the Rabbis, Mullah Aron, was evidently afraid of the effect discourse might have, and politely requested me to speak Hebrew, and not Persian; but I told him that since all were sinners, and stood in need of a Savior, it was my duty to declare the saving message in a language understood: ‘Why are we in the prison-bonds of the Ishmaelites, and treated as the dust under their feet? Why do the spoilers seize our property, and kidnap our daughters under their defiled roofs? Surely our sins and unbelief are the cause of this misery!’[34]

In general by the second half of the century, the misery and deprivation suffered by the Persian Jewish community had left it devoid of self-esteem and pride. The famine of 1871, poor hygiene due to squalid living conditons and various diseases, made the Jews desperate for any help that was offered to them.

However, during the twenty-five years of delay since the first approach of European Jews to Naser al-din Shah in 1873, until the establishment of the first Alliance Schools in 1898 , the first Christian missionary schools were established as early as 1876 in the ghetto of Tehran. Other schools that were established included those in Hamadan 1881, Isfahan in 1889 in and and Kermanshah in 1894. Having twenty to thirty Jewish children converted in the year 1891-2, the year was considered by the missionaries as the “year of spiritual harvest.”[35] To best connect with the Persians, the American missionaries provided evangelical, medical, and educational activities.[36] At stations in various cities, they offered hygiene and medical care, and, in the final quarter of the nineteenth century, opened separate schools for boys and girls. The key vehicle for their missionary activities, schools, were first established in Hamadan, and later in all major cities.[37]

Among the many different missionary societies mentioned that were involved in religious conversions were the Church Missionary Society of London, the London Society for the Jews and the American Presbyterian Missionary, all of whom worked in Iran on a cooperative basis.[38] The Reverend Robert Bruce from the Church Missionary Society of London was sent to Iran in 1869. He went to Jolfa, the Armenian suburb of Isfahan, with the intention of revising a Persian Bible which was accomplished by 1871. He also persuaded his Society to establish a mission in Iran named the Church Missionary Society. A number of Armenians of Jolfa became Protestants, and after 1900, medical and other work had begun in Isfahan. By 1935, missionaries were primarily in the four cities of Isfahan, Kerman, Yazd and Shiraz, with a commitment to cooperate and coordinate with each other.[39]

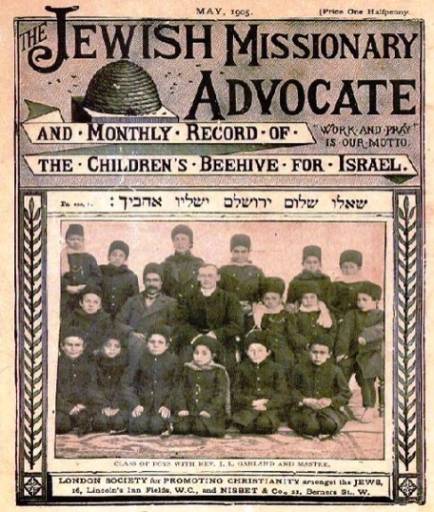

After having sent three missionaries in 1852 in response to the request of several converts from the leading Jews in Hamadan, the London Society of the Jews sent a missionary to that city in 1881 and another one in 1883 who remained in Iran only until 1884.[40] Among the first and most dramatic conversions influenced by this missionary are those of Mirza Nurollah, the son of the prominent Jewish physician of the royal court, Hakim Moshe. He was sent to England for training in 1884. Upon his return in 1888, in addition to his missionary work, Mirza Nurollah opened a school in Jubareh, the Jewish Ghetto of Isfahan which the Reverend J.L. Garland took charge of in 1897.[41]

London Society for Promotion of Christianity amongst Jewish Youth Courtesy of www.7dorim.com

By 1900, Mirza Jalinus, son of Hakim Shokrollah and the nephew of Mirza Nurollah, on his sister’s side, converted to Christianity.[42] Mirza Jalinus, being a physician as well, had a different impact on the Jewish community. Upon his death, another Jewish convert, the Reverend Iraj Mottahedeh, took over his mission.[43] The loyal services as native missionaries and educators of these new converts had a great impact on the life and education of the Iranian Jewish community.

Mirza Nurollah was later on appointed by the London Society to conduct two schools for Jewish children in Tehran, which were later taken over from the American Presbyterian Missionary.[44] The two schools were named Sedagat for boys in 1897 and Nur school for girls in 1898. Mirza Nurollah passed away in 1925 and his mission was continued by his daughter Gertrude, known as Miss Nurollah, and his nephew Mirza Jalinus, who had both been sent to England for education.[45] The school with two sections of boys and girls expanded with financial support from some Jewish community members, including a banker, Haj Eshagh Fahimian and a tailor, Yossef Darvish. The school gradually moved to different locations with larger space. By 1925, 200 boys and 150 girls were enrolled at the school with a faculty consisting of almost all new converts of Jewish descent.[46] The school was closed in 1937, but after WWII Miss Nurollah opened a new professional day school for girls .[47]

Graduation ceremony of Girls’ Nur school, 1962

Right to left: Mr. Soleyman Haim, Miss Nurollah the principal, unknown, Mirza Jalinus principal of boys Nur Sedaghat school, Hossein ‘Ala past prime minister and incombant minister of the royal court.

Courtesy of www.7dorim.com

As for Hamadan, the Station of London Society of the Jews was relinquished in 1904 and its work was transferred and continued by the American missionaries in that city.[48] Garland was put in charge of Isfahan in 1897 by the Anglican church [The London Society for Jews] to set up two schools, one [for boys] in Jubareh, the Jewish Ghetto, and one [for girls] in Jolfa, theArmenian section of the city.[49] Having Isfahan as his base, Garland sometimes visited the surrounding cities of Khonsar, Golpayegan, and Borujerd for his missionary purposes throughout his life.[50] In 1904, the boys’ school was transferred to Isfahan while the girls’ school continued in Jolfa until 1912. The boys’ school was later expanded and renamed Stuart Memorial College in memory of Bishop Stuart, the first missionary Bishop in Iran. In 1939 Stuart Memorial College was encorporated into the Iranian secondary educational system and was renamed Adab High School, from which many Jewish youth graduated.[51]

As Amnon Netzer reports, the school in Jubarheh was financially supported for years by Ishaq Sasson, a new Jewish convert. In spite of the existance of Alliance Israélite schools the Jubareh school survived, although with fewer and fewer students, until 1928. Reverend Garland passed away in Isfahan in 1932.[52]

The American Presbyterian Missionary, which had originally started its limited missionary work in Iran in 1834/35, was transferred to the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions in 1872. Under the new leadership, it followed the Church Missionary Society of London and the London Society for the Jews. The American group, under this new leadership, tried to reach the Iranians through the gates of evangelical, medical, and educational activities in the eastern and western parts of the country while the British focused on the southern regions.[53]

In 1887 an American school based on the US educational system was founded in Tehran by James Basset, who was later joined by Samuel Ward, another Presbyterian missionary. Mirza Nurroallah became the principal of this school in 1897.[54] However, probably the most appreciated educational activity of the American Presbyterian missionaries in Iran was the founding of two prominent schools for girls and boys which educated many Jewish and non-Jewish students. Their first girls’ school in Tehran, later named Iran Bethel School, was founded in 1874, with only 12 students. The school was located near the American Church, providing board and clothing, and was tuition-free. At the end of the first ten years, the school moved into a new location inside the mission premises. Jewish and Zoroastrian girls applied for admission since 1888, but no Moslem girl attended the school until much later. By 1898, the school turned into a day school with no further free tuition.[55] Miss Jane Doolittle took over as principal of the girl’s school in 1921. The name of the school was first changed to Nurbakhsh and by 1935 to Reza Shah Kabir.[56] Nevertheless, Miss Doolittle continued with another girls’ school which carried the name of Iran Bethel until the late 1960s, when the school was transferred to the Girls’ College of Damvand, headed by Dr. Francis Gray.[57] Many Iranian Jewish or non-Jewish girls attended that school to enhance their education.

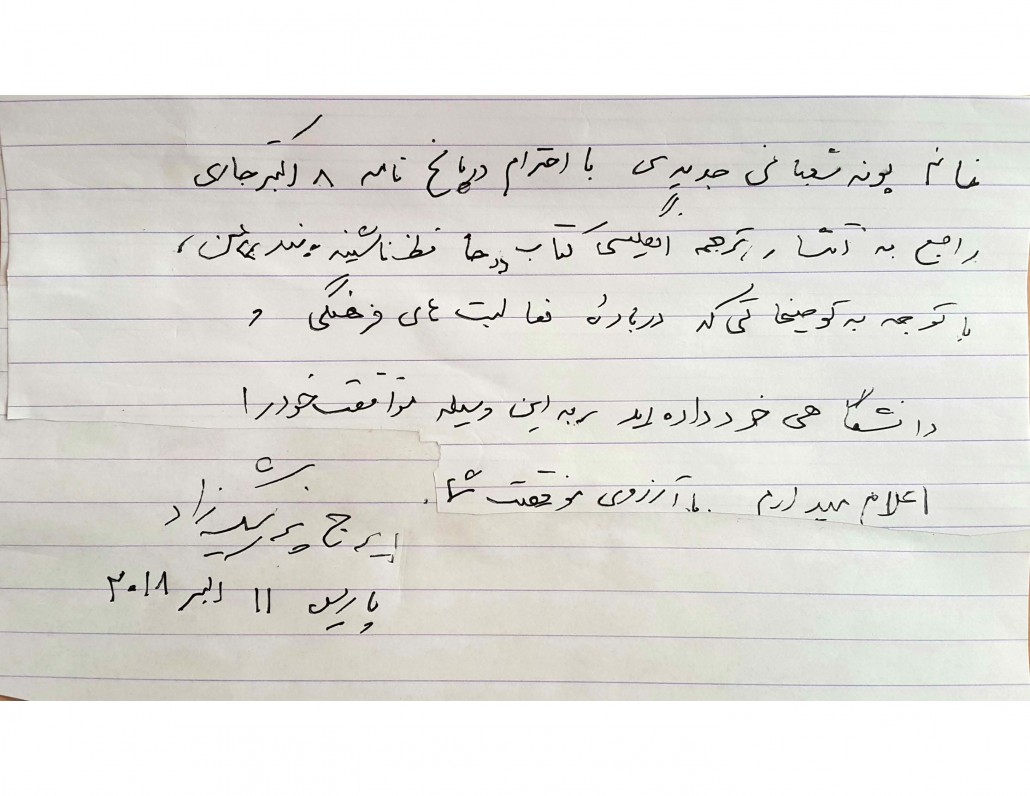

The American College for boys, changed into Alborz College in 1935, was the most renowned achievement of the educational activities of Christian missionaries in Iran. It was founded in in 1873, almost two decades before Alliance Israélite, for the purpose of converting Iranian Jewish and Armenian boys. The school was directed later on by Dr. and Mrs. Samuel Jordan from 1898. The missionary couple carried out an extensive promotion campaign for the expansion of the school with the addition of full college-level work. By 1935, the school requested to be identified by the Persian name, Alborz College, yet still maintain the initials of the American College of Tehran (A.C.T.). Both schools, the American College and Nurbakhsh, preserved the highest standard of education, and, played a tremendous role in the education of Iranian youth of all faiths until they were taken over by the Iranian government in 1939.[58]

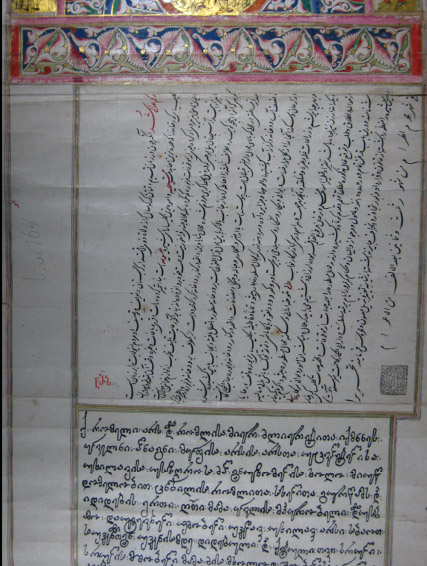

Another area of full cooperation between the British and American parties were the Church-synagogues named “Penial Churches” which were established by the London Society and Presbyterian Church in 1894, much to the resentment of the people of Hamadan. Such combined church-synagogues and assemblies were also held in Isfahan and Tehran. However, the station in Hamadan was relinquished in 1904 and the work was continued by the American missionaries.[59] In the case of Isfahan, the church was composed entirely of Jews, and was a part of the Church of England under the auspices of the Anglican Bishop in Isfahan, with close connection to the church in Tehran. This effort allowed Jews to pray with the translated Old and New Testaments by 1900, in both Judeo-Persian and Persian scripts, provided by the London Society for the Jews.[60]

In the areas of hygiene and health services, the establishment of hospitals by the British, American, Russian and French missionaries brought modern medicine into both major and small cities, places where otherwise no form of modern medicine was practiced.[61] It is through these missionary medical establishments such as the Church Missionary Society that some Iranian Jews were introduced to Western modern medicine and Western physicians, which in most cases resulted in the voluntary conversion of the students or their families to Christanity as well in order to access these services. The establishment of a British hospital in Isfahan, in 1914, known as the Morsalin Hospital taught Western medicine to many Jewish and non- Jewish students.[62] Subsequently a women’s hospital was founded,[63] where, in addition to offering medical services, women were trained as nurses. Among students of Jewish descent, Dr. Shokrollah Hakhamimi trained as a physician and Mrs. Iran Hakhamimi as a nurse.[64] Eventually the mission sponsored new maternity hospitals in cities of Yazd (1898), Kerman (1901), and Shiraz (1924). It was in these cities where doctors pioneered surgery for the carpet weavers.[65] Medical services of the Presbyterian missionary were also offered in the city of Rasht since 1905, where a hospital was later established. After WWI, hospitals’ financial aid attracted many needy patients among the Jews, Assyrians and Armenians. However, the hospital was taken over by the Soviet Government, but later controlled by American missionaries again.[66]

Although Protestant missionaries were of great service to Iran in the fields of medicine and education and opened many doors to future progress, the Christian message was not widely accepted among Muslims. Nevertheless, their evangelic causes offered through medical and hygienic services brought Jewish patients, for the most part, closer to the physicians and nuns who helped heal their bodies and souls, resulting in many conversions in almost all the cities where they rendered their services.[67]

One of the main tasks of Christian missionary activities was the distribution of pamphlets and stories infused with Christian doctrine, translated into Judeo-Persian to be read by Jews. For this undertaking, they required Christian Jews who understood Hebrew.[68] In the first half of the century, except for some missionary publications in Assyrian for distribution in Urumiah and Azarbayjan, basically not much Persian language material had been published. Reportedly an effort was made to publish some books by a missionary representative named C.G. Pfander from the Basle Mission in Caucasus, without much success.

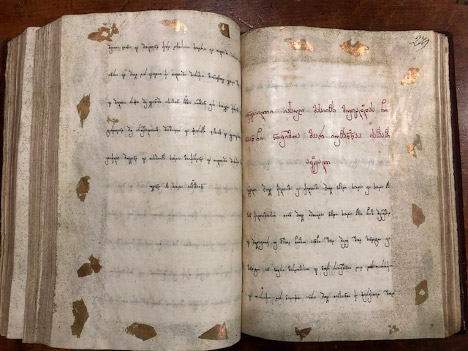

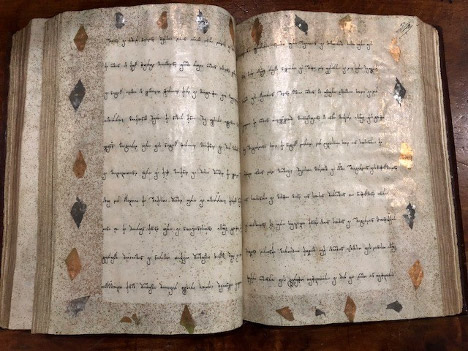

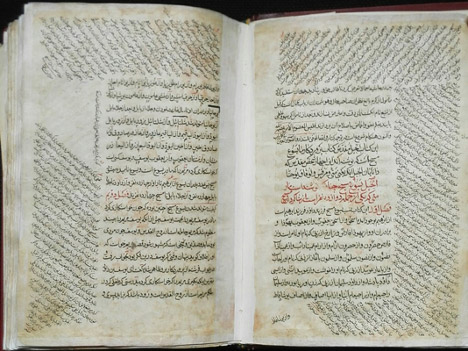

As early as 1840, the British missionaries attempted to translate and transliterate the books of the New Testament into Persian and Judeo-Persian for the Jews in the northeast and southwest of Iran. In 1847, the first translation of the Gospels, transliterated into Judeo-Persian was printed in London to be distributed amongst the Jews of Persia.[69] The fierce resistance of Persian Jews towards these efforts was not only expressed by the majority of Jews in those communities where the mission tried to get a foothold, but also by the unique literary product which very clearly encouraged their conversion.[70] The translation of the well-known medieval polemical treatise on the life of Jesus, Toldoth Jeshu, into Judeo- Persian in 1844 was no doubt motivated by the desire to resist the activities of the Christian missionaries of that time, giving the Jews a defensive weapon in their discussions with the missionaries.[71]

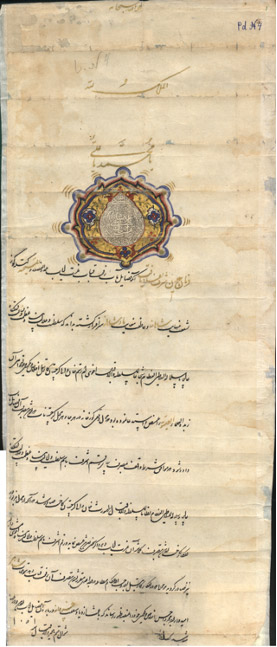

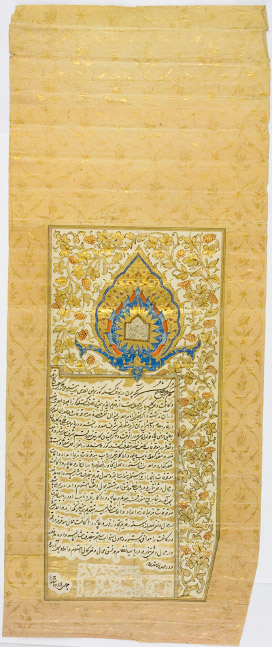

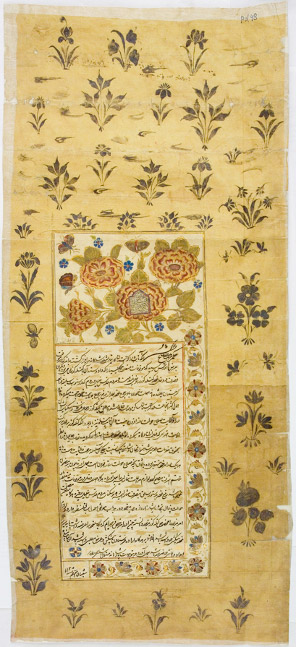

The London Society also initiated to translate the Old Testament, specifically the five Books of the Torah (Pentateuch) into Judeo-Persian. Upon the request of the British Bible Society, Mirza Nurollah took upon himself the task; if not for his efforts, “the Christian missionary might have failed all together.”[72] The book was published in London in 1895 and then distributed among the Jewish population in Iran. Mirza Nurollah’s effort was continued by two other Persian Jewish converts, his cousin Mirza Khodadad, and his nephew and cousin Mirza Jalinous, both the descendants of Hakim Eshagh who helped translate and transliterate the entire Old Testament into Judeo-Persian, which later on found its way into every Jewish household.[73]

One can assume that the choice of some Iranian Jews to convert to Christianity, moving from one marginalized minority group to another, involved different elements than those for conversion to Islam. The direct access of the missionaries to the very heart of Jewish families could have been a crucial point, such as the case of Henry Stern’s acquaintance with the family and sons of Hakim Moshe on his first trip (1844) and his visit to a synagogue in Kermanshah during his second trip (1852). These contacts were provided by the submissive attitude of the Jewish leaders, inviting the missionaries into their homes and synagogues and the persistence of the Hebrew-speaking missionaries using their biblical and Persian knowledge in their interactions.

The desperate need for schools and the thirst for education sent many Jewish children to missionary schools, especially when free board and clothing were initially provided.[74] Lack of knowledge about Judaism, in particular its philosophical and ethical values made the missionary arguments convincing and impressive. The novelty of the church-synagogue assemblies held in Persian, a language which they could understand and relate to, brought more people to the prayer chapel, and finally the conviction of the Messianic Arrival, the concepts of redemption (salvation and deliverance), absolution (forgiveness of one’s sin) as well as ascendance to heaven by accepting Christ seemed attractive to some.[75]

As an example of their efforts, a missionary report of 1891-1892, refers to the year as the “year of the spiritual harvest,”[76] averaging about 20-30 Jewish student conversions per year. Nevertheless, with the opening of Alliance Israélite, Iranian Jews became less accessible to the influence of the missionaries. A historian of the Protestant Missionary writes: “Among the Jews the fond hopes of the early days have not been fulfilled…The close connection of the Jews with the Jewish world outside Persia and the munificent donations of the French Alliance Israélite make the Jews less accessible to missionary influence.”[77]

Altogether the percentage of Jewish conversion to Christanity dropped after the establishment of the Alliance in Iran and the Jewish pride created after the Balfour Declaration of 1917. During the reign of the Pahlavis and the departure of most missionaries the rate of conversion further decreased. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, in spite of all the covert conversion of Iranian Moslems to Christianity, we hardly hear of a Jewish conversion to that faith. The new Jewish converts abroad were basically divided into two groups, those who joined Presbyterian churches or reverted back to Judaism.

Conversion to the Bahā’ī Faith

The Bahā’ī faith began in 1844 with Seyyed Ali Mohammad-e Bab (1820-1850), who proclaimed himself to be the “Gate of God” through which man “can pass into the chamber of beatitude and true faith.”[78] In 1863, he was followed by the prophetic proclamation of Mirza Hossien Ali Nuri (1817-1892), later named as Bahā’ullāh. His son and successor Abdul-Bahā (1844-1921), expanded the social ideas of the faith; his grandson and successor, Shoghi Effendi (1897-1957) envisioned a global perspective to the faith.[79]

The rise of the Bahā’ī faith came in the midst of Persian socio-political and economic stagnation. This progressive and tolerant movement with its high level of morality was enough to be seen by some Persian Jews as their salvation.[80] For the first time, the Jews found Persian-speaking friends within another religious minority.The Bahā’ī Faith, with its initial flexibility and ability to redefine itself during its formative period, achieved global success and expansion.[81] In contrast to Islam, the adoption of Bahā’ī faith did not necessitate abandonment of deep-rooted social, family, marital, and business relationships. It was possible for most Jewish converts to continue with their observance of Jewish rituals and holidays, thus making the transition less culturally and socially dramatic. By the same token, intermarriage with families of non-Jewish backgrounds did not occur in Kashan until 1929. For a short while, Jewish Bahā’īs had their own kosher butchery and separate Spiritual Assemblies. However, by the 1930s, the flexible religious identity and loose associations that had been one of the key elements in the growth of the movement were challenged by an institutionalized form of religious confirmation.[82] The process of consolidation under the leadership of Shoghi Effendi made it more difficult to sustain multiple religious identities, producing a more tightly-knit Bahā’ī community in which memberships to any other religious community were no longer acceptable. Such developments were partly the cause of the declining rate of growth of the Iranian Bahā’ī community by the 1950s. The reversed openness that once enhanced dialogue and exchange is a key to understanding the drastic decline in the number of Bahā’í conversions.[83]

For both the middle-aged converts and inquisitive youths, change seemed to be the answer. The Bahā’ī Faith’s departure from certain Islamic and Jewish principles raised special interest in Iranian Jews. These points of departure include, among others: the abolition of the concept of impurity freed Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians from the old Shi’a stigma; the inheritance law based on equality, preferable over both Jewish and Islamic Shi>a laws of apostasy; the emancipation of women and the forbiddance of holy war.[84] This attitude was even reported by Leon Loria, a teacher of Alliance in Hamadan (1903-1909) as he reports on 30 August 1908 that:

…. It can be stated without exaggeration that nine-tenths of the Jewish population of Hamadan are affiliated with the Bahā’ī sect…They [Bahā’īs] are extremely tolerant….will not accept any differences in treatment of Muslims and non-Muslims, reject all directives concerning the nedjes and allow their wives to walk in the street freely and without veils, They also reject Polygamy.[85]

The strong Iranian and mystical cultural commonality that the Bahā’ī Faith shared with the other religions of the area was missing in the Western cultural novelties imported by Christian missionaries. It was easier to accept Bahā’ullāh’s messianic claim than to accept Christian concepts like the Holy Trinity and the Original Sin.[86] Furthermore, lack of rooted philosophical and cultural education on Judaism left many unprepared for religious debate specially to some biblical references.[87] Mirza Abul-Faza’el Golpaygani of Golpaygan was a disciple of Bahā’ullāh. In his “Evidence and Proof of the Truth of the Bahā’ī Religion,” he tried to give genuine biblical prophecies to prove the validity of Bahā’ullāh’s messianic claim in support of one of the first books, the Book of Iqan (The Book of Certitude), written in 1862.[88] Some of the biblical references by Golpaygani and others include the entire chapter eleven of the Book of Isaiah (Isa: 11) starting with “A shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse and a branch shall grow out of his root……” which speaks about the arrival of a new Messaiah;[89] furthermore, William Sears, in his Thief in the Night, particularly elaborates on the same book (Isa 62:2 ) “…..and thou shall be called by a new name that the mouth of the Lord will give…” reasoning the “new messiah” is Bahā’ullāh and his followers are the Bahā’īs.[90] The number 2300 mentioned in the Book of Daniel in his dream, regarding the time needed for the restoration of the Sanctuary, (Dan. VIII:14) “ ……For two thousand three hundred evenings and mornings…….”, he interprets the days and night as years, to have ended in 1844 when the founder of the Bahā’ī faith proclaimed himself as the Bab.[91] The accidental exile of Bahā’ullāh to Palestine (Holy Land, in Acre and Haifa) enhanced the effect of the Jewish connection (Hosea II:15) with their faith, and a strong impact on Iranian Jews who were looking for a savior.[92]

At this point, with the aid of sophisticated Jewish converts, some parts of Bahā’ī writings were translated into Hebrew, first distributed in Hamadan.[93] In addition, resentment towards strict Jewish clerical authority, in terms of religious observations like those pertaining to the Sabbath, often pushed Jews to Bahā’ī gatherings for spiritual support and fulfillment. In general, the Bahā’ī attachment and its base in Israel, as well as the efforts of its promoters to find biblical indications as the proof of the Bahā’ullāh’s messianic role, created a feeling of familiarity and continuity for Jews.

The center of Jewish Bahā’ī converts was formerly in Hamadan but due to the efforts of the Alliance Israélite teachers the number of converts decreased considerably and the movement went to the Jews of Kashan and Tehran.[94] According to Ehpraim Neumark, the Pole who visited Hamadan in 1883/4, there were about eight hundred Jewish families in Hamadan, approximately one hundred and fifty of whom were Jews who had converted to the Bahā’ī religion.[95] We also hear from Rabbi Yeuda Kopelioviz who visited Iran in 1928 and remarked upon the fast spread of the Bahā’ī religion affecting Jewish communities of Isfahan and Shriaz. The extent of the impact was so significant that it was even mentioned in the charter of the Hadassah Society of Jewish Women in Iran-Hamadan. In their charter, paragraph #12 stated that “the Society endeavors to influence the Jewish women not to take part in Bahā’ī meetings.”[96] Kopelioviz noticed that despite the Alliance school in Hamadan, founded in 1900 in the Jewish quarter, many Jewish children attended the Bahā’ī school located in the same area.[97]

The geographer Dr. Abraham Jacob Brawer who visited Iran in 1935 raised the astonishing question: “After all, the Bahā’īs too are persecuted in Iran, so what in fact does the Jew gain when instead of a persecuted Jew, he becomes a persecuted Bahā’ī?.”[98] One reason he offers is that the Bahā’ī accepts all prior prophets, including Zoroaster and Buddha, but all of them are outdated and that the last messenger is Bahā’ullāh, as hinted in the Book of Daniel, the Evangelist texts and the Quran. His second reason is the “simplicity of Bahā’īsm, its universality and the relinquishing of many commandments put upon by other faiths.” Nevertheless, Brawer believed that the country’s modernization and the return to Zion “put an end to the Jew’s fascination with Bahā’īsm.[99]

Walter Fischel regarded the idea of messianism as the focal point, since Bahā’ullāh claims to be the long awaited Messiah, as Mahdi of the Muslims, the Messiah of the Jews, the savior of Christians and the Saoshyant of the Zoroastrians.[100] Habib Levy believes that the universal concepts of the unity of the family of man and moral values of the Bahā’ī religion attracted the Jews, especially the educated ones. However, he adds that these concepts had already been introduced and spread by the Jewish prophets, but the alienation from Jewish values and ignorance with regard to the essence of the Jewish religion, not only by the population at large, but also among educated Jews, allowed Bahā’īs to infiltrate different levels of Jewish people.[101]

Unlike conversion to Islam, conversion to the Bahā’ī faith was not to be an abrupt conversion. Neither did it necessitate abandoning deep-rooted social ties involving many kinship, marriage and business relationships. This transitional period would help a newcomer enter with the psychological assurance that one did not have to make a choice between one’s past and present, but rather gradually adopt the new faith. But once the new demand for formal enrollment (tasjil) were established, since the 1930s, laws related to marriage and prohibition against working on Bahā’ī holidays were strictly enforced. These developments coincided with, and may in part explain the decline in the rate of growth of the Iranian Bahā’ī community by the 1950’s.[102]

Netzer observes that a considerable number of the “Baha’i Jews” in Iran, particularly in Hamadan and Kashan, reached the highest prestigious ranks in the organizations and leadership. It is reasonable to assume that: those Bahai’s of Jewish origin, who had received a modern education in the Alliance schools, where they acquired fluent French and also mastered the English language, spearheaded the spread of the new religion world wide.[103]

Conclusion

The motives and authenticity of religious conversions of the nineteenth century regardless of what religion, can be understood in the socio-economic and cultural background of Persian Jewry in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The low number of voluntary conversions to Shi’ia Islam is understandable, considering the level of maltreatment and humiliation extended by the Muslim majority towards the Jews. Conversion to Islam was primarily for financial gain or promotional purposes whereas, conversions to Christianity and the Bahā’ī faith were likely more genuine, especially seen in those new converts who so passionately dedicated their lives to be active leaders and promoters of their new beliefs. Whereas, a new convert in Islam, however, still bore, at least for one generation, the stigma of Jadid al-Islam, or “new convert.”

Fulfillment of spiritual and emotional needs as well as practical issues within Judaism such as Jewish inheritance and divorce laws which favored male members of the family provoked conversions to other faiths. Furthermore, the new religious affiliation would provide them a larger circle of socio-cultural, economic and political benefits. Overall, however, considering the level of commitment and observance of the new converts, Bahā’ī conversion, in spite of the great persecution that the young religion faced, seems to have been the more successful and lasting one among former Jews.

A study on the first generation of Iranian Jews, following their emancipation, which entitled them to national and limited civil rights, would probably be a true test of the authenticity of prior conversions. The scope of this evaluation should take into consideration those Iranian Jews who at the approach of modernity, in order to fulfill their intellectual and spiritual needs, instead of conversion chose either to go abroad for education or continued their studies at home at the limited facilities available in Iran at the time. This evaluation can also look upon the time when the gates of Israel and other democratic countries were opened to Jews for migration, giving them the long awaited spiritual security.

Coming from a closed and traditional community, Iranian Jews were mostly taught midrashic accounts and strict halakhic and traditional rituals. As a traditionally orthodox community, unlike Western Jews, Persian Jews were never guided through religious channels to face issues of modernity or benefit from reformation. Rabbi Kopelioviz concerning Jewish education in Iran says:

General ignorance among the people also affected religious issues. There are no learned Torah Scholars in Iran. The rabbis are not scholars..…Needless to say that they are not capable of having educational impact on the Jewish community….they do not have the power to conquer the hearts of the young….[104]

The same observation was made by Dr. Brawer who noted that: “ …the lack of knowledge of the Torah and tradition made it easy for the Bahā’īs & Christians to capture Jewish souls.”[105]

Brawer also commented on the indifference of the Jews of Iran towards those who converted to Christianity and Bahā’īsm: Such indifferent attitude is most noticeable since the converts

live in one courtyard with their Jewish relatives, celebrate Passover and eat together in their homes [kosher food] and go to the synagogue on Yom Kippur and do not even forget to atone.[106]

Brawer also observed that [some] Jews took advantage of financial help and other benefits of conversion, such as hospital care and the availability of suitable jobs.[107] With regard to the rate of conversion, Kopelioviz considered the Alliance as an active factor in the assimilation of Iranian Jews [due to their secular approach of education].[108] In this respect Amnon Netzer also believes that:

Although the Alliance and the Zionist movement were major factors in halting the wave of conversions, one may say nonetheless that, to a certain extent, they were also factors that pushed the intellectuals towards assimilation……[Not only] Alliance did not reinforce Judaism; on the contrary, it let to acculturation if not assimilation. [109]

With the glorification of nationalism during the period of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1925-1941) and the halt he put on political activities, Zionism could not have had an impact on the acculturated Iranian Jews who had the thirst for modernity.

Certainly in modern days, while middle-aged Jews can freely observe their faith in whichever level, from Orthodoxy to Reconstructionism in different Jewish communities, there are academic or non-academic centers available for inquisitive Jewish youth from any background. In academic Jewish institutions or even temples for those who practice religion, there are debate opportunities for those interested in the issues of modernity, secularism, and intellectualism or any other issue challenging Judaism in particular, and religion in general.

Such opportunities provide a rational and modernized approach in questioning spirituality and elements of Judaism without having the need to change one’s faith. Unfortunately, this was an opportunity that the Jews of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century in Iran were were not privileged to have.

[1]The Quranic verse 9:28, “Inama al-Mushrikun najs” meaning the “Idolaters are indeed unclean” has been interpreted differently throughout time. In early Islam non-believer meant “polytheist,”but later on the term implied to “non-Muslim.” As for Sunnis, “non-believer implies only to the polytheists, whereas, Shi>ites interpret and imply the term to followers of other monotheist faiths as well.

[2]Habib Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, 2nd ed., vol. 3 (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 422-423. Ephraim Neumark, born in 1860, moved to the Holy Land as a child with his parents. But at the age of 23, he traveled through Tiberias, Syria, Kurdistan, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. After his trip, he wrote his three-year travelogue which has been used by many leading researchers of Jewish society.

[3]Shulhan Arukh: (1488-1575 C.E. / 892-983 A.H.).

[4] סימחאה תור (SimhaTorah, rejoicing the Torah) Jewish celebration at the end of Sukkot.

Joseph Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours Among the Jews, Mohammedans and other Sects, 2nd edition (London: J. Nisbet, 1835), 128-129.

[5]Walter Fischel, “The Jews of Persia- 1795-1940” in Jewish Social Studies 8, no. 2 (April 1950): 122; E.G. Browne, A Year Amongst the Persians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1926), 241, 243, 320-21; Habib Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, 2nd ed., vol. 3 (Beverly Hills: Iranian Jewish Cultural Organization of California, 1984), 635, 744-747.

[6]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 127.

[7]Encyclopedia Britannica, S.V. “Capitulation Law”: A treaty whereby one state permitted another to exercise extraterritorial jusrisdiction over its own nationals within the former state’s boundaries.

[8]Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, vol. 3, 724-29, as reported from the notes of Soleyman Cohan Sedgh.

[9]Alliance Israélite Universelle, hearafter refered to as the “Alliance.”

[10]Amnon Netzer, “Establishment of the Alliance School in Tehran,” in Pdyvand 3 (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 98-99; Honoring the Founders of Alliance Israélite Universelle (New York: 1996), 46. The name of Bassan, as the first Alliance representative in Kermanshah is reported by both Amnon Netzer in Padyavand and the Honoring of the Founders book, as “M. Bassan -1904” with no first name recorded..

[11]Mehrdad Amanat, Negotiating Identities, Iranian Jews, Muslims and Bahā’īs in the Memoirs of Rayhan Rayhani (1859-1939), Ph.D. Dissertation (Los Angeles: University of California, 2006), 107.

[12]Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, vol. 3, 668-669, reporting from the memoirs of Rahim Misha’il. In 1892, Zulaykha ,the wife of Zaghi, converted to Islam in order to get divorced. She married the Muslim clergyman who right away claimed all the property of Zaghi for Zulaykha according to the Law of Apostasy.

[13]For divorce of Zolaykha and Zaghi; also see Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, vol. 3, 668-669.

[14]Levi, Trkh-e Yahd-e Irn, vol. 3, 635-36, 659-669.

[15]Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 146.

[16]Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 146-147.

[17]Heshmat Allah Kermanshahchi, Iranian Jewish Community: Social Developments in the Twentieth Century (Los Angeles, Ketab Corporation, 2007), 347-350. See also www.ostani.hamshahrilinks.org/Print?itemid=188651.

[18]Circa BCE700- 200 CE)

[19] Nestorian Church, also called the Assyrian Church of the East, views Jesus Christ as two different entities, one human and one divine, in one body. Nestorians have lived in Iran since the pre-Islamic era, having fled from the areas under the control of the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church. See Massoume Price, Brief History of Christanity in Iran, 2002, 6; www.farsinet.com/iranbibl/christians_in_iran_history.html.

[20]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 148.

[21]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 148.

[22]Amnon Netzer, Shofar of New York, September 1998, vol. 209, 22-23.

[23]Joseph Wolff, the world traveler and Christian missionary to the Jews in the Orient was born in Bavaria (Germany) to the family of a Jewish Rabbi. He converted to Catholicism in 1812, but because of his Heretical views, he moved to England and joined the Anglican Church around 1818/1819. He then joined the Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews (CMJ) which was set up in London about ten years earlier in order to help convert Jews.

[24]Joseph Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours Among the Jews, Mohammedans, and other Sects [see n. 5],138, 154-157. It is during this visit that the Qajar prince, Abbas Mirza, compared his missionary activity as “a wandering Dervish, who goes about as a man of God,” and he subsequently gave permission to establish a school at Tabreez, expressing his desire to see the nation civilized.

[25]Joseph Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours, 138,154-157.

[26]Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours, 136-137.

[27]Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours, 148.

[28]Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours,128-129.

[29]Wolff, Researches and Missionary Labours, 425.

[30]Joseph Wolff, Narrative of a Mission to Bokhara, in the Years 1843-1845, to Ascertain the Fate of Colonel Stoddart and Captain Conoly vol.1, 2nd ed. (London, J.W. Parker, 1845), 176.

[31]Henry A. Stern, Dawnings of Light In The East (London: Charles H. Purday, 1854), 196.

[32]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 147.

[33]Stern, Dawnings of Light In the Eat, 272.

[34]Henry A. Stern, Dawnings of Light In the East, 236-237; also refer to the conclusion, 272-278.

[35]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 148.

[36]Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Iran Mission, A Century of Mission Work in Iran (Persia 1834-1934) (Beirut: The American Press, 1936), 14-15. Also see Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 146.

[37]Massoume Price, Brief History of Christianity in Iran, 2002, www.farsinet.com/iranbibl/christians_in_iran_history.html, 9.

[38] A Century of Mission Work, 112, 14-15.

[39]A Century of Mission Work, 14.

[40]A Century of Mission Work, 14.

[41]A Century of Mission Work, 14-15; see also Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23.

[42]A Century of Mission Work, 14-15, 112; Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23. .

[43]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23.

[44]A Century of Mission Work, 15,

[45]A Century of Mission Work, 15, 88; Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, Article no. 11, 23; oral interview with Mrs. Agdas Sabi, a graduate of Nur school (20 July 2017).

[46]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23, 44.

[47]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 44; Netzer, Shofar, vol. 172, 28, 29, 60, June 1995.

[48]A Century of Mission Work, 15.

[49]A Century of Mission Work, 14-15, 112.

[50]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23.

[51]Ecyclopaedia Iranica, S.V. “ British Schools in Persia,” www.iranicaonline.org/articles/great-britain-xv; Church Missionary Society Archive SV. “Iran (Persia),” www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/church_missionary_society_archive_general/editorial/introduction/by/rosemary/keen.aspx; also, oral interview with Dr. Hushang Hakhamimi whose parents were educated at Morsalin Hospital (20 July 2017); oral interview with Dr. Shokrollah Baravarian who has attended Adab H.S. (22 July 2017).

[52]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 213, article no. 11, 23.

[53]Walter Fischel, Jewish Social Studies, 146.

[54]Netzer, Shofar, vol. 212, no. 9, 23.

[55]A Century of Mission Work, 86-88.

[56]A Century of Mission Work, 14-15,103; Oral interview with Mrs. Aghadas Sabi a graduate of Nurbakhsh H.S. (20 July 2017).

[57]For further information about Damavand College, see D. Ray Heisey, “Reflection on a Persian Jewel: Damavand College, Tehran,” Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia) 5, no. 1 (2011).

[58]A Century of Mission Work, 87; Netzer, Shofar 212, article no. 10, 23. For further information about Alborz College see: www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college.

[59]A Century of Mission Work, 14-15.

[60]“The Five Books of Moses”/ אספאר כמסה מאוסי/ اسفار پنجگانه موسی, Judeo-Persic Pentateuch, trans. Amirza Noorollah b. Hakham Hakim Moshe and Amirza Khodada b. Hakham Eliyahoo (London: British Hebrew Persian Bible Society, 1900).

[61]Encyclopaedia Iranica, S.V. “BĪMĀRESTĀN,” www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bimarestan-hospital-.

[62]“Church Missionary Society Archive Iran (Persia), Journal of Research on History of Medicine 2, no. 2, 2013, www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/church_missionary_society_archive_general/editorial/introduction/by/rosemary/keen.aspx; also oral interview with Dr. Hushang Hakhamimi (20 July 2017).

[63]The women’s hospital was founded and placed under the supervision of Dr. Emmelina Stewart.

[64]Oral interview with Dr. Hushang Hakhamimi, having both parents been trained in Morsalin Hospital(July 20, 1017).

[65]“Church Missionary Society Archive Iran (Persia),” Encyclopaedia Iranica, S.V. “BĪMĀRESTĀN,” www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/church_missionary_society_archive_general/editorial/introduction/byrosemary/keen.aspx. The hospital in Shiraz was funded by Ḥājj Moḥammad-Ḥosayn Nāmāzī.

[66]Netzer, Shofar 209, article no. 7, 45.

[67]Century of Mission Work, 56. Beyond the schools, hospitals were also “utilized as a center for evangelistic work,” bringing in similar results.

[68]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 149. Thus Garlan’s “A Christian Catechism for Jewish Pupils” (Isfahan, 1899) was transliterated into Judeo-Persian by a Jewish convert, but all the copies were later burned by the same person who did the translations. See Alliance Israélite (1901), 57. “Catechism” means religious questions and answers to be used to test some body’s religious knowledge in advance of Christian baptism or confirmation.

See also John Elser, The History of American Missionary in Iran, trans. Soheil Azari (Tehran: Nour Jahan Publishers, 1333 AH/1954),101. Prior to that in 1877, another book, named The Christian Dialogue, Ketab-e So’al va javab-e Massihi,was prepared for publication.

[69]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 149. According to the ‘British and Foreign Bible Society, authority from Calcutta was given to issue an edition of Henry Martyn’s translation. (See H. Martyn, Controversial Tracts on Christianity and Mohammdedanism, ed. S. Lee (Cambridge: J. Smith, 1824).

[70]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 149.

[71]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 149; http://www.princeton.edu/judaic/special-projects/toledot-yeshu/:

www.princeton.edu/judaic/special-projects/toledot-yeshu/. “The Book of the Life of Jesus(in Hebrew: Sefer Toledot Yeshu) presents a chronicle of Jesus from a negative and anti-Christian perspective. …..Perhaps for centuries, the story circulated orally until it coalesced into various literary forms.”

[72]Fischel “The Jews of Persia,” 149.

[73]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 150.

[74]A Century of Mission Work, 87.

[75]Meriam-Webster Dictionary, S.V. “Absolution”: “the act of forgiving someone for having done something wrong or sin”; “ a remission of sins pronounced by a priest (as in the sacrament of reconciliation).” “Redemption” means salvation; deliverance from sin.

[76]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,”148.

[77]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 151.

[78]Walter Fischel, “The Bahā’ī Movement and Persian Jewry,” Jewish Review (1984): 47-55. For the most updated conversion of Jews to the Bahai faith, see Amnon Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews to the Bahā’ī Faith: Early Period,” Irano-Judaica VI (Jerusalem, 2008), 290-323.

[79]Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 104.

[80]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 154.

[81]Amanat, Negotiating Identities,103.

[82]Amanat, Negotiating Identities,125-126, 174.

[83]Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 125.

[84]Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,”153-54.

[85]Honoring the Founders of Alliance Israélite Universelle, 37.

[86]Merriam Webster, S.V. “Original Sin”: “The state of sin that according to Christian theology characterizes all human beings as a result of Adam’s fall”; Merriam Webster, S.V.”Holy Trinity”: “the unity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead according to Christian dogma.”

[87]Wolff, Researches and Missionary, 54-55. See also Deut. 18: 15, 18; Fischel, “The Jews of Persia,” 156.

[88]Fischel, “ Jews of Persia,” 155; Abul-Faza’el Golpaygani, 1978, Rasā’el va raqā’em [1886-1913].

[89]Fischel, “ Jews of Persia,” 155.

[90]William Sears, Thief in the Nigh: The Strange Case of the Missing Millennium (Oxford: George Ronald, 1961),

[91]Fischel, “ Jews of Persia,” 155. The 2300 years mentioned in Daniel VIII:14 were said to have come to an end in 1844 C.E. (period of Daniel’s prophecy B.C.E. 456 + 1844 C.E. rise of Bab= 2300 years). For further biblical (old and new) as well as books of other faiths regarding the validity of the year 1844 as the year for the arrival of the new messianic prophecy, see Thief in the Night: The Strange Case of the Missing Millennium.

[92]Fischel, “ Jews of Persia,” 155; Hosea II,15: “ I will make the valley of Achor, a door of hope.”

[93]Fischel, “ Jews of Persia,” 155; see also Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 5.

[94]Fischel, “Jews of Persia,” 156.

[95]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews,” 303; reports from Neumark, 81.

[96]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews,” 304.

[97]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews,” 304.

[98]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 304.

[99]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews,” 306.

[100]Fischel, “Jews of Persia.,” 154.

[101]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews,” 309.

[102]Amanat, Negotiating Identities, 24-126.

[103]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 318.

[104]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 304.

[105]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 305.

[106]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 305.

[107]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 305.

[108]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 304.

[109]Netzer, “Conversion of Iranian Jews ,” 316.

![“[Hamid Naficy] Self Portrait!,” 1996, Rice University.](https://www.irannamag.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3-3-4e-fig11.jpg)