The Complete Persepolis: Visualizing Exile in a Transnational Narrative

Leila Sadegh Beigi received her PhD in English literature from the University of Arkansas, where she is an instructor of literature. Her writing focuses on the intersection of gender, exile, and translation in contemporary Iranian women’s literature. Her recent publications include “Simin Daneshvar and Shahrnush Parsipur in Translation: The Risk of Erasure of Domestic Violence in Iranian Women’s Fiction” in the Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies (Duke University Press, 2020) and “Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Embroideries: A Graphic Novelization of Sexual Revolution across Three Generations of Iranian Women” in the International Journal of Comic Art (John Lent, 2019).

Contemporary Iranian women writers create a voice of resistance in fiction by questioning and redefining gender roles, which are defined by culture, tradition, and state law in Iran. They narrate their stories of resistance in a state of exile, a condition rooted in marginalization independent of geographical location. In this article, I will examine and analyze The Complete Persepolis, written by Iranian writer, artist, and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi, as a transnational narrative written in exile. A transnational perspective challenges the binary division between the Eurocentric “First World/Third World” framework of modern global feminist analyses.[1] Satrapi’s narrative in The Complete Persepolis focuses on a gendered and discursive manifestation of women, culture, and identity, problematizing “a purely locational politics of global-local or core-periphery in favor of viewing the lines cutting across these locations.”[2] I argue that The Complete Persepolis expands the notion of exile through the visual representations of the author’s concerns about the status of women in exile at home and abroad. The portrayal of internal exile, or exile at home, relies on images of women struggling with gender discrimination, sexism, and censorship, all of which limit and marginalize them as female citizens. In the portrayal of external exile, or exile abroad, Satrapi offers images of women experiencing racism, stereotyping, and marginalization in the West.

The graphic representation of human emotions through the perspective of a young girl experiencing gender discrimination at home and racial discrimination abroad creates a space of empathy and understanding for readers. As Scott McCloud argues, “The wall of ignorance that prevents so many human beings from seeing each other clearly [can] only be breached by communication.”[3] Satrapi breaks the “wall of ignorance” through strong visual imagery unveiling the identity of Iranian women. As a transnational hero, the protagonist, Marji, breaks cultural, ideological, and geographical barriers, and calls for global solidarity, understanding, and equality for immigrants in exile. Of course, not all immigrants are exiled subjects. What lies at the heart of exile is the lack of choice. Edward Said writes: “Exile is not, after all, a matter of choice: you are born into it, or it happens to you.”[4] Exile, banishment, and stigmatization are described by Said as distinguishing factors and specific characteristics of exile.[5]

My argument is in line with two critical debates on the neccessity of reshaping transnationl feminism. The first is Chandra Mohanty’s model of transnational feminism in her articles “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles” (2003) and “Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique” (2013). In “Under Western Eyes Revisited,” Mohanty suggests that “a transnational feminist practice depends on building feminist solidarities across the divisions of place, identity, class, work, belief, and so on.”[6] Mohanty calls for individual and conscious effort to use these differences to connect; “Under Western Eyes Revisited” focuses on “decolonizing feminism, a politics of difference and commonality, and specifying, historicizing, and connecting feminist struggles.”[7] A decade later, in “Transnational Feminist Crossings,” Mohanty emphasizes the importance of “re-commit[ting] to insurgent knowledges and the complex politics of antiracist, anti-imperialist feminisms.”[8] Mohanty writes: “I believe we need to return to the radical feminist politics of the contextual as both local and structural and to the collectivity that is being defined out of existence by privatization projects.”[9] She emphasizes the significance of a systematic analysis of power which depoliticizes the resistance and the social movements by the privatization of organizations and feminist antiracism in the neoliberal academic landscape. This is not about the risk of homogenization and stereotyping of differences of women in the Global South, which Mohanty discusses in an earlier article, “Under Western Eyes” (1986); this is a critique of the institutionalization of radical feminist antiracism, which aims to erase the race and class divisions which unite the voices of women locally and globally to preserve power.

The second critical debate, Nima Naghibi’s articulation of transnational feminism, discusses cross-cultural feminist misunderstandings in her book Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism and Iran. Naghibi writes: “The problem of sisterhood remains, however, the inherent inequality between ‘sisters.’ Often using the veil as a marker of Persian women’s backwardness, Western and (unveiled) elite Iranian women represented themselves as enlightened and advanced.”[10] Like Mohanty, Naghibi calls for destabilizing and reinterrogating transnational feminism’s elimination of race and class divisions between “the civilized nations” and “rogue nations.”[11]

Satrapi’s Persepolis contributes to these debates on transnational feminism by portraying Iranian women’s struggle to manifest the powerful and thriving feminist voices of the nation. Satrapi’s discursive approach to diversity, oppression, and resistance is interwoven with culture and politics of local and global feminist discourse calling for unity and solidarity. The narrative criticizes gender discrimination in Iran, but it also questions racial discrimination in the West. Persepolis examines the visual representation of discrimination against women and gender-based violence in Iran, and it problematizes the demonized representation of Iran and Iranians in the West resulting in global marginalization of Iranian women. While the visual medium influences the writer’s ability and effort to push the boundaries of Iran’s traditional society in the narrative’s demands for a democratic space to include women, the medium also offers an antiracist reading of women from the Global South in the West.

The concept of exile is significant in understanding Persepolis as a transnational narrative because exile encapsulates the space for a transnational exchange of culture. Exiled subjects leave their homeland, and they build a diaspora community in their new country, operating as transnational identities to represent their homeland, culture, and literature. While both Iranian women and men in diaspora have contributed to the Iranian literary tradition, “women writers have been largely responsible for making Iran and the postrevolutionary immigrant experience visible in literature. Women writers of the Iranian diaspora especially appear to have comfortably left behind any concerns about adhering to the tradition of Iranian letters and have instead made writing one of the most important media for representing their particular experiences of exile, immigration, and identity.”[12] Although both diaspora and exiled writers inform transnational and intellectual identities, the exiles are particularly grounded in the notion of punishment due to their radical political views. Drawing on Said’s discussion of exile, I prefer to use the term exile in this article because exile is not always defined as the state of being away from home; rather, in the case of contemporary Iranian women writers, exile could also be defined as the state of being marginalized and alienated from the public in their own country due to their capabilities of writing about women’s limitations.

In the case of Satrapi, exile has provided a condition for her to visualize her memories, practicing her radical criticism of the political landscape locally and globally, which resonates with Said’s definition of intellectuals in exile who have obtained a “sharpened vision.”[13] For example, Satrapi problematizes Western media as representing Muslims as “terrorist[s],” and Iran’s media as “making anti-Western propaganda.”[14] This is an example of her fairness in criticizing both governments in their policies. Satrapi’s laser sharp focus on cultural and political representation in Persepolis perfectly illustrates that her narrative, as Said puts it, “provides a different set of lenses” to read her homeland.[15] Persepolis not only represents her sharp critical vision in exile, but it also provides an alternative lens through which to view Iranian women. Analyzing Persepolis as the first graphic novel in the Middle East written by an Iranian intellectual woman in exile offers a feminist version of exile challenging the conventional understanding of intellectual exile discussed by Said.

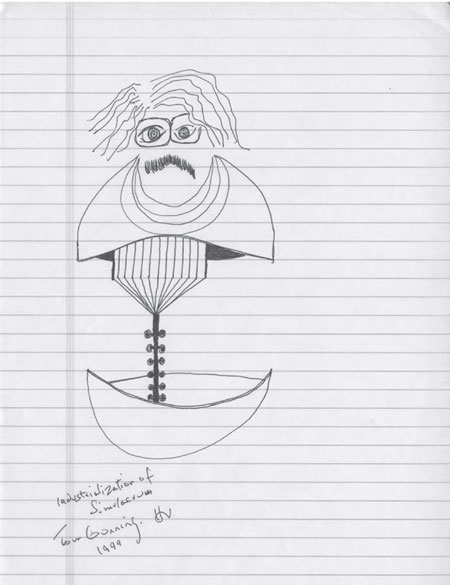

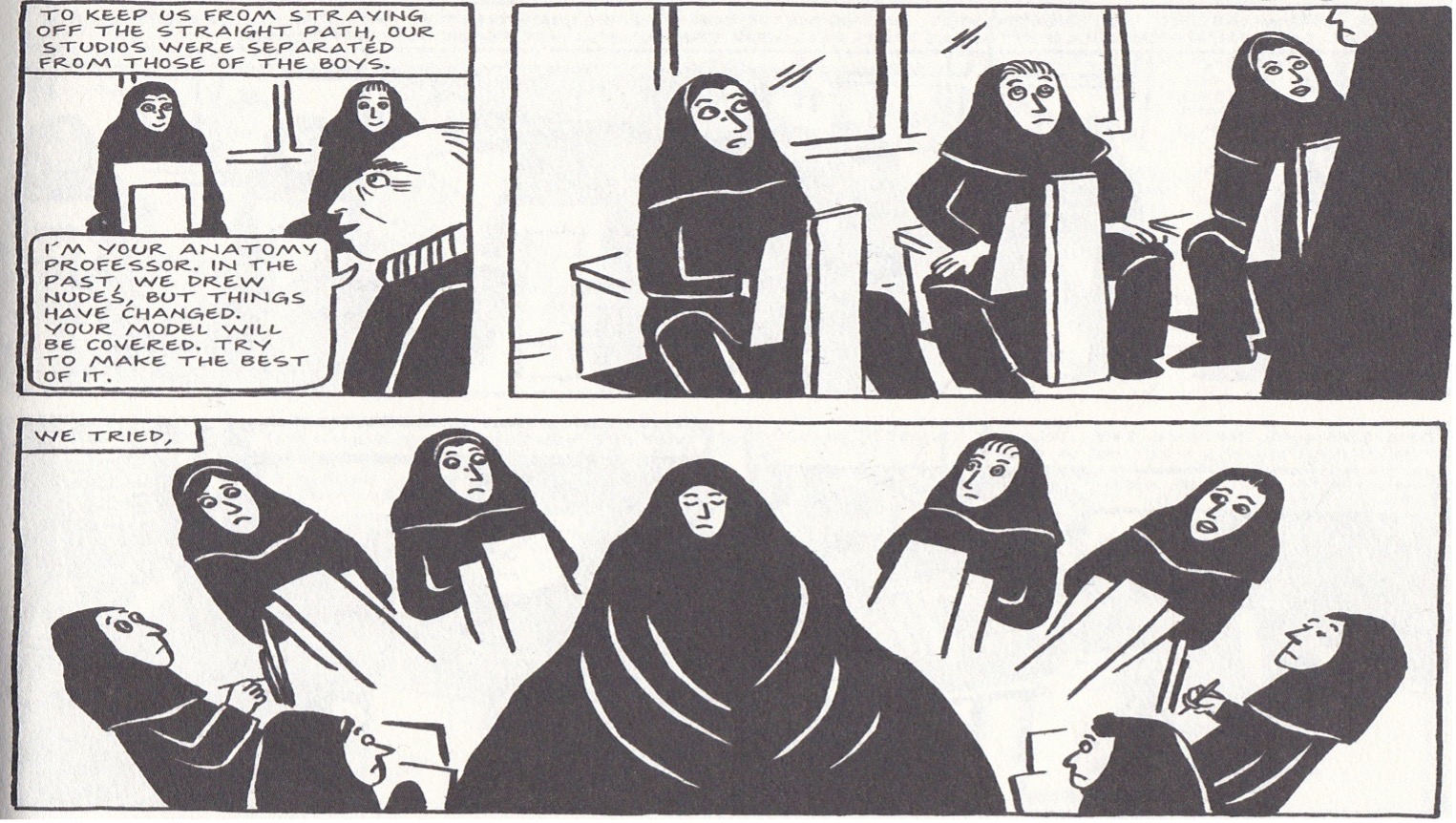

The subversive potential of female heroes in Iranian culture and literature is not censored or erased in Persepolis. Nevertheless, Satrapi’s commentary on the lack of freedom of artistic expression in Iran draws attention to one of the most important aspects of exile at home: artistic productions being subject to censorship under Islamic law. Despite her success in obtaining an art degree at the graphic school in Tehran, Satrapi suffers from a lack of freedom, this time as an artist in Iran. Censorship in art makes Satrapi ask herself, “where is my freedom of thought? Where is my freedom of speech? My life, is it livable?”[16] There are limitations for presenting women’s bodies not only in painting, but also in any other art form. To do so, an artist is required to obtain consent from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Marji resists these oppressive conditions in her brave objection to the female students’ dress code at the university. In a scene where the university has organized a lecture on the theme of “moral and religious conduct,” Marji opposes the lecturer’s views on the female dress code, saying that “you don’t hesitate to comment on us, but our brothers present here have all shapes and sizes of haircuts and clothes. Sometimes, they wear clothes so tight that we can see everything.”[17] She also questions the lack of freedom in drawing faces and bodies in the art studios (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 299. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

She finally faces her double exile by leaving Iran for France to build her identity as a successful writer and artist in a country where she does not face restrictions or censorship in producing art and publishing her stories. Inspired by Satrapi’s living in exile, her performance in The Complete Persepolis is the embodiment of a discursive manifestation of women and culture.

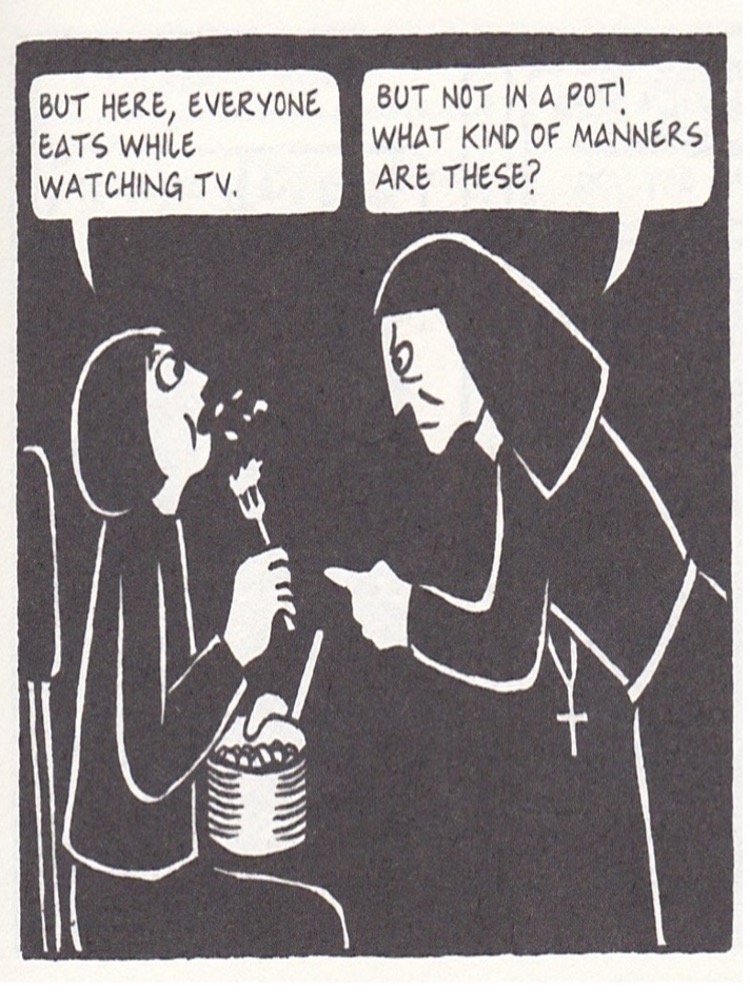

Crossing the borders and breaking the barriers of thoughts and ideas enables writers in exile to see with a “different set of lenses” using “exile’s situation to practice criticism.”[18] While Satrapi’s graphic novel fits Said’s definition of being able to see problems in the West as well as in her own country, it also uses a gendered lens to show women intellectuals in exile. Satrapi is critical of the Eurocentric behavior she witnesses in Vienna at several points in the novel. For example, in a scene in the religious school she attends, Marji is punished for eating in the TV room. A nun tells her, “it’s true what they say about Iranians. They have no education.”[19]

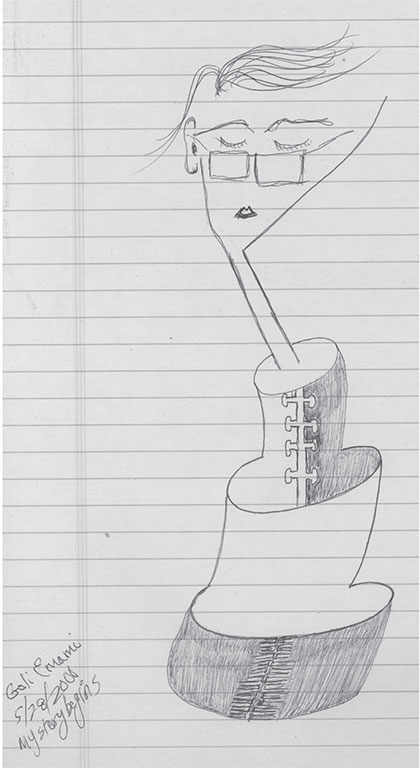

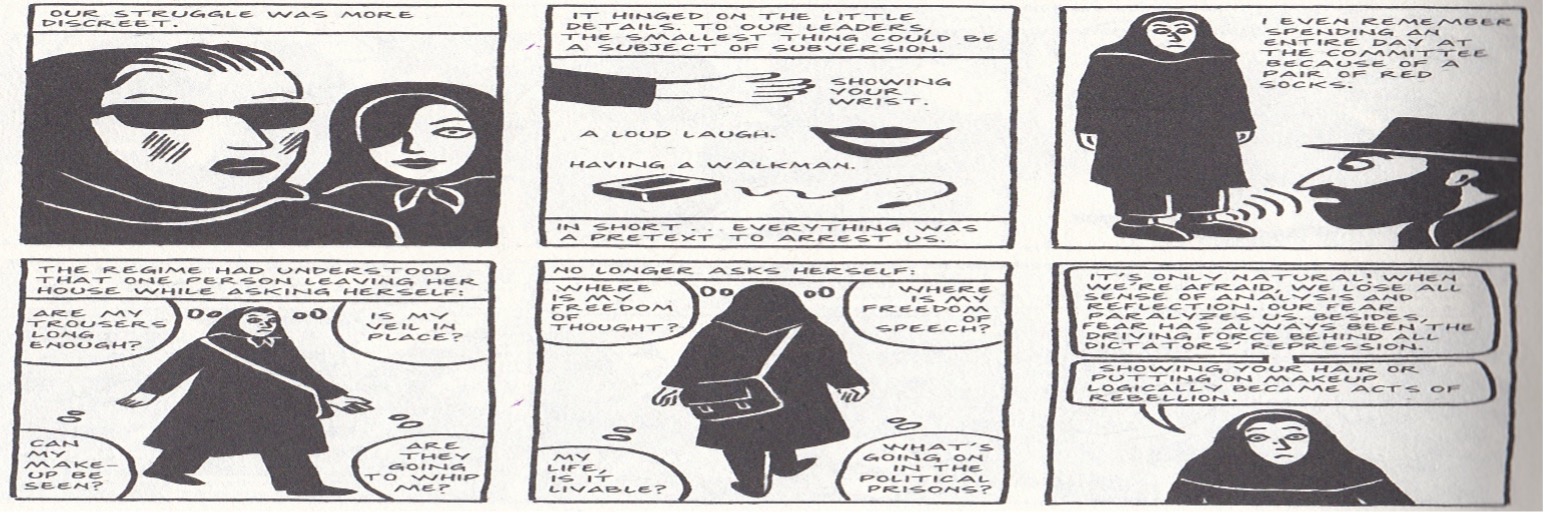

Satrapi rediscovers her new Iranian identity in the West by acknowledging Third World–women’s struggle to survive, and she depicts women’s resistance, subversion, and rebellion to confront the restrictions on their appearance and behavior in public (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 302. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Persepolis captures the nuances of Iranian society by depicting Iran as a dynamic nation and underscoring the significance of women’s resistance. While Satrapi’s approach to depicting women in Iran celebrates the vibrancy and power of Iranian women, her storytelling in Persepolis is inclusive, with its multi-perspective lens on culture, class, politics, faith, and gender in Iran.

The distance from home poses challenges for exiled writers, who risk creating “single story” narratives about their home country;[20] however, Satrapi’s inclusive narrative does not reflect a “single story” narrative about Iran. The Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie discusses how culture is composed of multiple stories and the authenticity of depictions of culture depends on the representation of the multiple stories about it.[21] It is not possible to know in totality a culture without engaging with all possible stories about those people or places. Adichie observes that “the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are not true, but that they are incomplete.”[22] Although it is not the job of one writer to represent a culture in its totality, it is the responsibility of a writer not to distort or misrepresent the culture. In this article, I discuss the multilayered representation of culture and women in Persepolis, highlighting its subversive narrative, which circulates to transnational audiences multiple representations of women’s resistance.

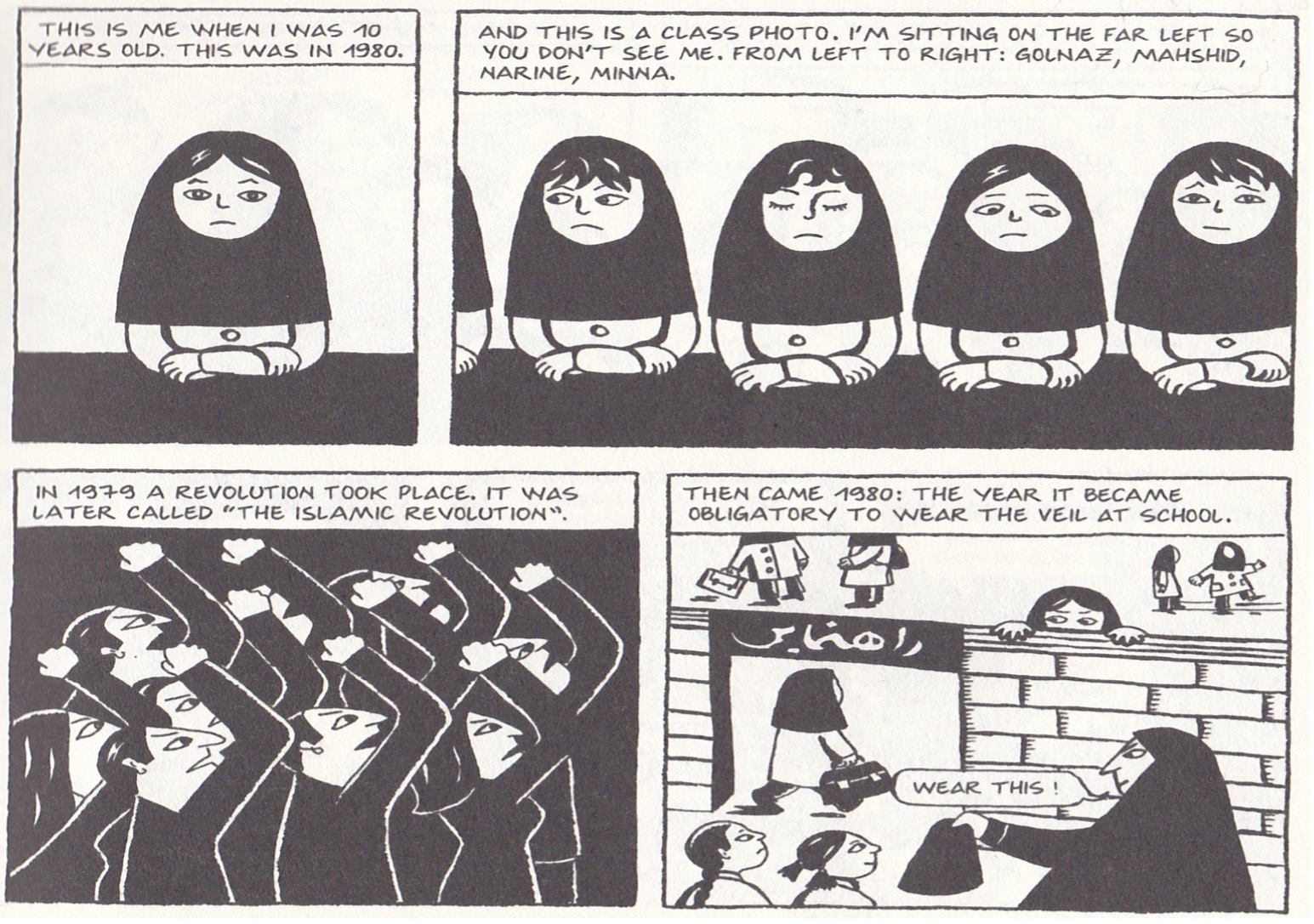

Satrapi responds to the political tensions between Iran and the West by creating Marji, her transnational hero. Marji narrates her observations of Iran, which has been less known to the West and Western audiences since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Diego Maggi argues that Satrapi’s Persepolis “complicate[s] and challenge[s] binary divisions commonly related to the tensions amid the Occident and the Orient, such as East-West, Self-Other, civilized-barbarian and feminism-antifeminism.”[23] My argument in this article builds on Maggi’s argument about how Satrapi pushes the boundaries to bridge the gap between worlds. For example, Satrapi depicts the political turbulence through her childhood memories by opening the novel when she is only ten, and as a result of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, she is wearing the hijab while sitting in a sex-segregated school (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 3. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

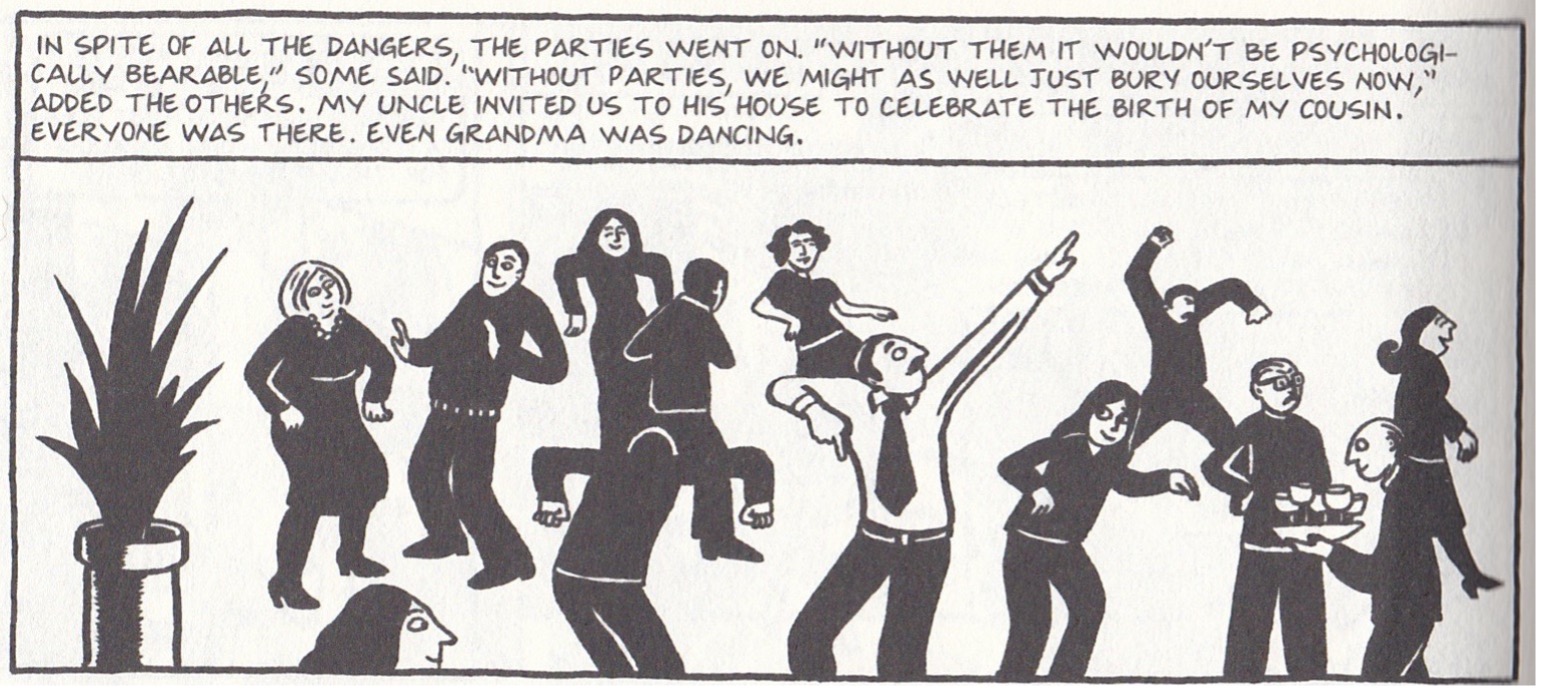

In another scene, she reveals the ordinary life of people trying to survive under the strict Islamic regime, a difficulty which has become compounded by the country’s new restrictions on ordinary activities like dancing and throwing parties (Figure 4). She writes: “In spite of all the dangers, the parties went on. ‘Without them it wouldn’t be psychologically bearable,’ some said.”[24] Revealing a new version of reality through the portrayal of the private and public in her narrative, Satrapi tells the story of ordinary people, reminding Western readers that people are people, with common interests and ideas despite the cross-border differences in cultures.

Figure 4. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 106. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Satrapi offers an understanding of the cultural and political complexities of Iranian society, and as an intellectual in exile, she consciously uses these differences to connect to the struggle of women globally. In her book, Women, Art, and Literature in the Iranian Diaspora, Mehraneh Ebrahimi discusses the creation of visual arts as well as graphic novels by diaspora writers and artists in the humanities as an essential factor to inform a global community and to combat xenophobia. By showing women’s struggle for freedom and peace in a local and global context, Persepolis decolonizes the narrative about Iran as evil Other and Iranian women as victims. Marji’s experience traveling across borders accounts for her hybrid identity and resists projecting a stereotypical representation of Iran and Iranian women as “Other.” For example, Marji draws attention to cross-cultural behaviors and attitudes when it comes to religious extremists, who exist in all societies. As mentioned earlier, there is a scene where Marji carries her food to the TV room to enjoy while watching a show in the religious school in Vienna (Figure 5). When she is told to watch her behavior by “the mother superior,” Marji says, “but here, everyone eats while watching TV.” The mother gets angry and says, “it’s true what they say about Iranians. They have no education.”[25] After this confrontation, the nuns decide to expel Marji from school, and Marji thinks, “in every religion, you find the same extremists.”[26]

Figure 5. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 177. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Race, class, and gender differences rooted in sociocultural and political aspects are historicized in Persepolis for a Western audience. The narrative combats the West’s binary understanding of Iran and the West as black and white and instead offers an alternative image. The visual imagery in Persepolis unveils the culture and history of Iran and the identity of Iranian women for the Western audience. As an intellectual Iranian woman writer, Satrapi captures the key events from pre-revolution, post-revolution, and wartime, and their social problems to perfectly communicate with the audience through her privileged position as an elite. Although she tells the audience what life was like for a girl of her generation, class, and family background, her narrative does not suggest the life story of “all” Iranian girls during the years the book is set. For example, the stories of the girls who were terrified and traumatized by war and were forced to come to Tehran because their houses were destroyed are not included in Persepolis. These girls were misplaced in the schools in Tehran. While they had already faced the trauma of war in their hometowns, the atmosphere of the metropolitan capital intensified their repression. They faced struggles because of their accent, different skin color, and different appearance, but they still had to obey the strict rules for hijab at schools and in public.

A full and accurate representation of Iranian women requires a multilayered narrative that gives equal voice to women with different experiences and backgrounds. Many scholars discuss Satrapi’s narrative as being close to the facts in its portrayal of Iran and Iranian women. For example, Farzaneh Milani writes: “Marjane Satrapi celebrates the Iranian people’s history of resistance, subversion, and rebellion as much as she bears witness to the miseries and injustices caused by political and religious dogmatism.”[27] Women’s struggle of resistance is not lost in Persepolis; instead, the traumatic experience of the years after the Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War is part of the focus. Indeed, Satrapi responds to Iranian women’s literary tradition as a contributor to that tradition. Persepolis depicts three generations of female characters: Marji, her mother, and her grandmother are portrayed as women conscious of their rights and their identity in fighting back against oppression. These characters bring their unique perspectives on the sociocultural issues that affect women’s everyday life in Iran. For example, Marji’s mom joins the demonstration against compulsory veiling, Marji shouts at the two guardians of the revolution who stop her in the street and warn her not to run, and the grandma removes the stigma around divorce when Marji is full of fear and hesitation after her divorce.[28]

By expressing their sexual experiences, adventures, and concerns through the portrayal of their personal lives, these characters represent strong women with activist perspectives as active agents during the years the novel is set. The narrative provides the Western audience with a glimpse into the joy and pleasure in the lives of women amidst their constant struggle for peace and equality, creating empathy and understanding that transcends borders.

Satrapi’s Persepolis attempts to reflect the voices of Iranian women as being in resistance to oppression rather than as being submissive. The high rate of readership of this graphic novel among Western readers is due to Satrapi’s success in showing a compelling and alternative image of Iranian women. Women writers exiled abroad risk telling a “single story” narrative about Iran, but they may take a similar risk in representing their homeland by catering to Western preconceptions about it. Hamid Dabashi discusses this risk in his book Brown Skin, White Masks, demonstrating “how intellectuals who migrate to the Western side of their colonized imagination are prone to employment by the imperial power to inform on their home countries in a manner that confirms conclusions already drawn.”[29] Because Satrapi’s narrative is critical of both Iran and the places she lived in the West, I don’t find it problematic that Persepolis is written for a Western audience. Indeed, the dual nature of women’s resistance to the oppression is portrayed through the author’s double critique of Iranian fundamentalism and Western imperialism. While Persepolis depicts the conflict between democracy and dictatorship in the shah’s regime, it simultaneously problematizes democracy and fundamentalism under the Islamic Republic. In fact, by criticizing the pro-American shah, Satrapi criticizes imperialism and American and British interference in Iran.[30]

As a very popular form of storytelling in the West, the graphic novel integrates text with imagery. While the use of visuals helps to interpret the author’s imagination, those images are also open to readers’ interpretation. In Persepolis, Satrapi remembers her past through a “process of visualization,” which indicates the multiplicity of ways her culture can be interpreted.[31] It also speaks about her exilic perspective, providing her with a hybrid identity with multitudes of lenses. Satrapi’s combination of dialogue, interior monologue, and image promotes myriad ways to understand Iranian culture. Satrapi presents Iranian culture as complex and filled with strong female figures, including the protagonist herself.

Women’s common struggle connects Satrapi to the struggle of other Iranian women writers, her foremothers despite their differences in time, language, and genre. Iranian women writers have depicted women’s struggles against the patriarchal system, traditional gender roles, and limitations for women under the Pahlavi regime and Islamic Republic. The struggle of women through different historical periods in Iran reflects the type of struggle the female protagonists face in novels written by Iranian women. Marji’s radical thoughts and her criticism of the sociopolitical discourse of Iran, particularly in the 1990s, represents the evolving generation of women performing an alternative role as the symbol of change and innovation.

Satrapi contextualizes sisterhood in her narrative and brings migrant women to visibility by showing her observation of discrimination and marginalization as an immigrant woman in Vienna. In Persepolis, Satrapi fairly represents the disciplinary nature of fundamentalism and oppression for women both in Iran and in the West. For example, she represents two “Guardians of the Revolution” in the streets of Tehran, whose jobs were “to arrest women who were improperly veiled,” such as herself (Figure 6). Later, the nuns in the Viennese religious school try to control the girls’ behavior in public (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 133, 177. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

By juxtaposing the visual imagery of Iranian and Austrian fundamentalists who are dressed in similar fashion, with head coverings and concealing clothing, Satrapi points out the similarities of religious fundamentalism, which oppresses women cross-culturally. This juxtaposition highlights the fact that while religious-based oppression occurs in Iran, similar oppression occurs in the West, though those living in the West often overlook the latter. This resonates with what Mohanty believes to be the importance of “cross-border feminist solidarities,” which are based on women’s struggles for emancipation in various parts of the world.[32] Though the religions are different, their power to oppress and subordinate women is grounds for alliance.

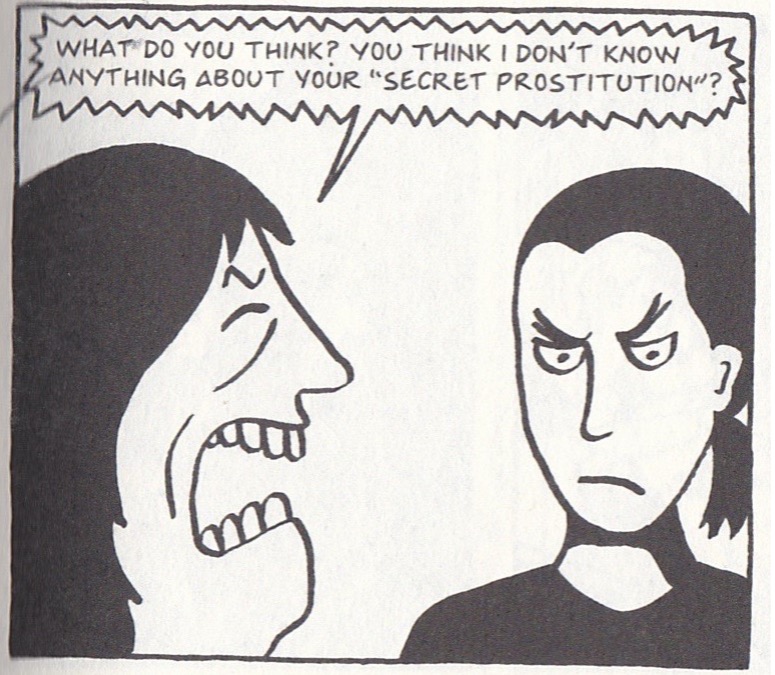

Satrapi’s struggle as a woman living in exile is portrayed through the moments that Marji faces racial discrimination in Vienna based on the stereotypes of women from the Global South. For example, Satrapi depicts her bitter experience when her Austrian boyfriend’s mom accuses Marji of “taking advantage” of her son; in Marji’s words, “She was saying that I was taking advantage of Markus and his situation to obtain an Austrian passport, that I was a witch” (Figure 7). When Marji is forced to leave her boyfriend’s house, she goes home and surprisingly finds similar aggression at her own house when her landlady calls her a prostitute (Figure 7). Later, her landlady accuses Marji of stealing her jewelry, saying that “I lost my brooch. I’m sure that you’re the one who took it.”[33] The narrative criticizes the condition of women in exile abroad in the West and the West’s treatment of immigrant women.

Figure 7. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 220, 221. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Persepolis is not aimed at vengeance for the author’s traumatic experience in the West; it is aimed at questioning the very idea of sisterhood through the book’s critical approach to women’s oppression in exile. Satrapi’s portrayal of racism resonates with Naghibi’s call for destabilizing and reinterrogating transnational feminism to eliminate race and class divisions between “the civilized nations” and “rogue nations.”[34] Persepolis calls for reconsideration both of sisterhood and of race as the foundation of transnational feminism, and urges its audience to not overlook the significance of an antiracist feminism anchored around women’s common force of resistance across the globe. Satrapi’s diverse and discursive manifestation of racial and cultural diversity through the black-and-white panels in Persepolis is in itself commentary on the reductive Western division of the world into black and white.

Iranian women’s unequal status at home, rooted in gender discrimination, and their marginalization in the West, rooted in Islamophobia and racial discrimination, is central to Satrapi’s model for change and reformation. Her critique of the representation of Iran and Iranian women in the West underscores how these misrepresentations create inequality between women of different cultures, which in turn problematizes sisterhood. Female bonding and friendship, which is portrayed at multiple points in her narrative both in Iran and in Vienna, is a direct reference to the significance of solidarity. Satrapi’s demand for inclusion and equality in Persepolis resonates with Naghibi’s argument on the significance of an “alternative model to sisterhood.”[35]

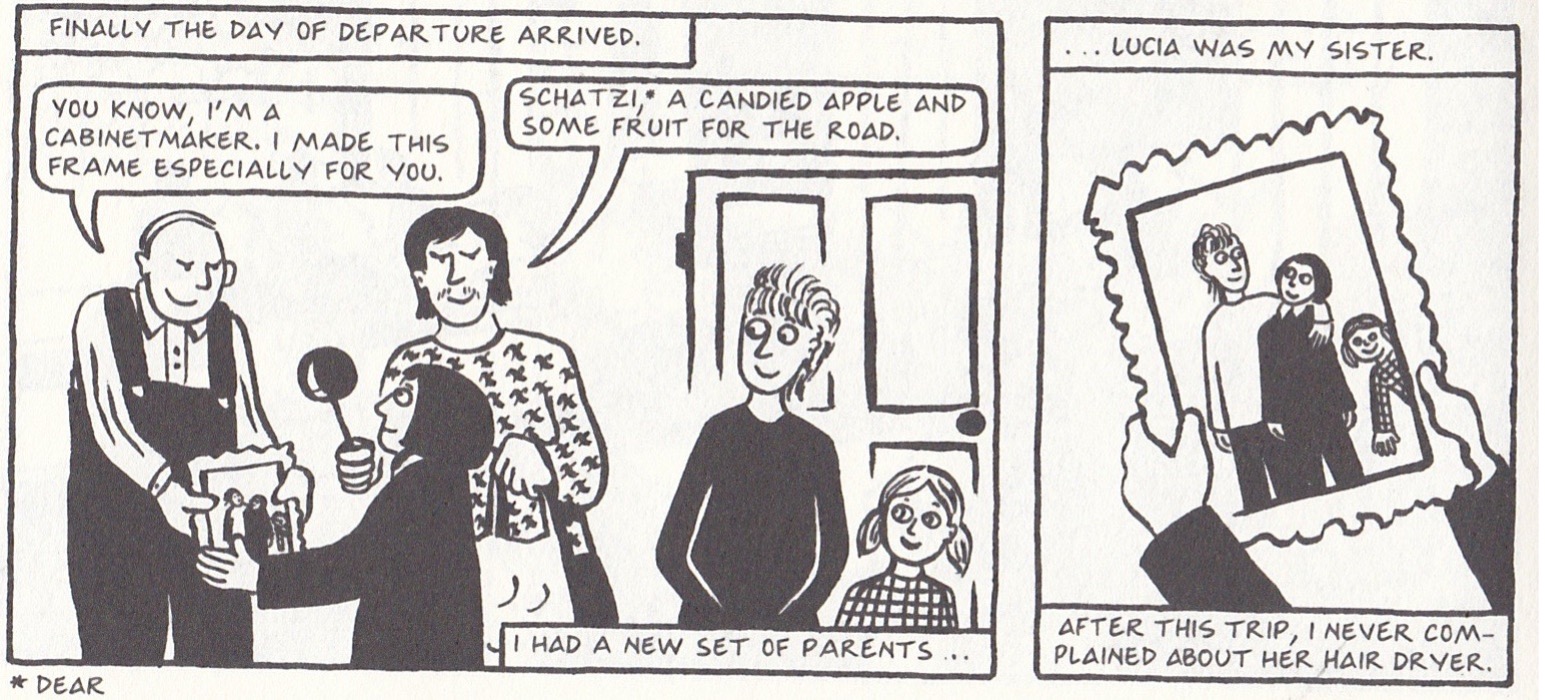

The power and importance of sisterhood in making peace and sharing pains and sorrows to resist oppression is portrayed at several points in Persepolis. For example, during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–88), Marji’s family host and support Mali’s family after their house is bombed during Iraq’s attack on the south of Iran. When Mali, a family friend, with her husband and two kids, knocks on the door of Marji’s family home in the middle of the night to seek shelter, Marji’s mom hugs Mali and says, “hey, it’ll be OK, calm down…you did the right thing to come here.”[36] They laugh and cry together to get through the devastation of wartime and to get Mali’s family back on their feet.[37] Later in Vienna, Marji’s classmate Julie introduces Marji to new friends with whom Marji feels loved and gains a sense of belonging, making her life more bearable.[38] Marji’s roommate, Lucia, noticing Marji’s loneliness before Christmas break, takes Marji to stay with her family in Tyrol for Christmas. After this trip, Marji loves Lucia like a sister (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 172. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

My own perspective as an immigrant scholar who has experienced life and work in Iran and the United States has been shaped by Eurocentric behavior aimed at marginalizing me and people like me. With the presidency of Donald Trump and the growth of Islamophobia after he called Iran a “terrorist nation,” the situation grew worse. At that time, I was teaching Persepolis in my World Literature class at the University of Arkansas and observed firsthand the power of Persepolis to transcend borders. Persepolis was welcomed by the students, who were accustomed to hearing and thinking about Iran as a land of horror and evil. As my students experienced, Persepolis opens the audience’s eyes to the differences that are historically and politically constructed. Indeed, Satrapi problematizes both Western and Iranian media in using political frames to portray the enemy by demonizing and dehumanizing the whole nation.[39] This is an example of her fairness in criticizing both governments in their policies, a criticism that points to the politics of differences in a global context. Her narrative doesn’t promote Islamophobia and hatred; it questions the political framework between Iran and the West in representing the other side as evil.

The transnational circulation of people’s lives, ideas, events, and culture through the eyes of Marji plays a significant role in facilitating for the Western audience an understanding of Iran and what it means to be an Iranian woman. As Amy Malek argues, “Persepolis is an exemplary model of both memoir and Iranian exile culture in that it pushes the boundaries of both and that Satrapi’s position of liminality allows her to use a third space position from which to complete her cultural translation, in which she addresses issues of identity, exile and return.”[40] Mobilizing popular culture from the Middle East in the West for the first time, Persepolis draws attention to the relationship between the regions. This is in line with Mohanty’s argument on the necessity of uniting the voices of women in resistance around the world regardless of the divisions of race and class. Persepolis is a vivid picture of the Iranian sociocultural context concerning women’s issues during and after the Iranian Revolution.

The alternative representation of Iran that Satrapi provides without censorship invites the audience to rethink stereotypes of Muslim women as passive victims and of Iran as a backward and barbarian nation. The narrative is free from censorship and has not been co-opted to help the West to advance their agenda in the Middle East. Indeed, the transnational hero, Marji, breaks the barrier of ignorance and misunderstanding about the Middle East as Evil Other. By sharing her observation of events, women, and culture through images and words that communicate to the Western audience without the interference of governments, Marji enters the hearts and minds of readers around the globe. The oppression and struggle of Iranian women for equity and peace is a different struggle based on the specific sociopolitical atmosphere in Iran. However, what makes the narrative in Persepolis transnational and cross-border is its representation of women’s resistance and power during the political upheavals and wartime in Iran. Persepolis has great potential to shift the focus from understanding Iranian women as lacking agency, as they are presented in Western media or books like the bestseller Reading Lolita in Tehran. Persepolis marks the first time that Iran has been represented through images in a graphic novel created by a woman from the Middle East, and signifies the need for renewal and reshaping cultural exchange.

In conclusion, Persepolis’s representation of contemporary Iran offers interdisciplinary ways to know Iran for the new generation. It opens the space for discussion on how gender, religion, and politics work in Iran. The narrative shows that to find solidarity in sisterhood, we need to understand our differences and appreciate our commonalities. The divisions between class, race, religion, culture, and ethnicity as shown in the narrative point to, as Mohanty discusses, the “politics of difference and commonality, and specifying, historicizing, and connecting feminist struggles.”[41] Persepolis educates the Western audience on Iran as a different civilization to explore. Satrapi stresses the significance of self-education at several points in the novel, saying that “one must educate oneself.”[42] In the transnational world we live in, education is the key to expanding our vision across geographical boarders. Persepolis offers hope that the progress of women’s rights can be made through mutual understanding and support in solidarity with sisters across the world.

What lies beyond the race, class, and culture divisions in my argument is the significance of storytelling that reflects resistance in exile. I believe that Satrapi’s experience of exile at home and abroad, the traumatic condition of marginalization, provides a sharp focus in the creation of her narratives that question the status quo and depict women’s nuanced resistance to oppression. The cost of Satrapi’s resistance appears in the author’s exile. While throughout history exiles share similar “cross-cultural and transnational visions,” as Said argues,[43] Satrapi’s Persepolis is a byproduct of the West’s imperialism and Islamophobia alongside religious fundamentalism in the twenty-first century, and stresses the common force of oppression. Persepolis represents the author’s observation of the disciplinary nature of fundamentalism and oppression against women both in Iran and in the West, contributing to Valentine Moghadam’s argument in her book Globalization and Social Movements: The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives. Moghadam argues that the mobilizing forces of uniting women at the “macro level” and “micro level” create a “collective identity” to overcome the differences across the globe.[44]

The visualization of the estrangement, alienation, and homelessness through the exiled hero, Marji, cultivates the imagination to move beyond the self and differences. Drawing on cross-continental conversations amongst people and in particular women from around the world, Persepolis focuses on solidarity in exile. The contemporary themes of emigration, Otherness, exile, and identity connect Satrapi’s transnational narrative to the stories written by women from other cultures like The Distance Between Us: A Memoir by the acclaimed Mexican writer Reyna Grande and Americanah by Adichie. The global intersections and parallels in exile literature connect human experience cross-culturally, and manipulate transcultural visions in storytelling which connects women and culture to find solidarity and seek healing and collaboration. Persepolis is a provocative account of the Iranian people’s everyday life and concerns, much like those of many other people in the world, who struggle with their belief systems and those of their governments. Persepolis suggests that in order to maintain collective identity, we need to subscribe to women’s emancipation and gender equality in all cultures and nations. Persepolis provides a stellar example of the creativity and power of Iranian women writers’ storytelling abilities.

[1]Susan A. Mann, Doing Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 362.

[2]Mann, Doing Feminist Theory, 363.

[3]Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: William Morrow, 1994), 198.

[4]Edward W. Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 184.

[5]On the differences between exile, refugees, expatriates, and émigrés, see Said’s discussion in Reflections on Exile, 181: “Although it is true that anyone prevented from returning home is an exile, some distinctions can be made among exiles, refugees, expatriates, and émigrés. Exile originated in the age-old practice of banishment. Once banished, the exile lives an anomalous and miserable life, with the stigma of being an outsider. Refugees, on the other hand, are a creation of the twentieth-century state. The word ‘refugee’ has become a political one, suggesting large herds of innocent and bewildered people requiring urgent international assistance, whereas ‘exile’ carries with it, I think, a touch of solitude and spirituality. Expatriates voluntarily live in an alien country, usually for personal or social reasons. Hemingway and Fitzgerald were not forced to live in France. Expatriates may share in the solitude and estrangement of exile, but they do not suffer under its rigid proscriptions. Émigrés enjoy an ambiguous status. Technically an émigré is anyone who emigrates to a new country. Choice in the matter is certainly a possibility. Colonial officials, missionaries, technical experts, mercenaries, and military advisers on loan may in a sense live in exile, but they have not been banished. White settlers in Africa, parts of Asia and Australia may have been exiles, but as pioneers and nation-builders, they lost the label ‘exile.’”

[6]Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles,” Signs 28 (2003): 499–535. Quote on p. 530.

[7]Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique,” Signs 38 (2013): 967–91. Quote on p. 977.

[8]Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[9]Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[10]Nima Naghibi, Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism and Iran (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), xvii.

[11]Naghibi, Rethinking Global, 141–46.

[12]Persis M. Karim, “Reflections on Literature after the 1979 Revolution in Iran and in the Diaspora,” Radical History Review 105 (2009): 151–55. Quote on p. 152.

[13]Said, Reflections on Exile, xxxv.

[14]Marjane Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis (New York: Pantheon, 2004), 322.

[15]Said, Reflections on Exile, xxxv.

[16]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 302.

[17]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 297.

[18]Said, Reflections on Exile, xxxv.

[19]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 177.

[20]Chimamanda N. Adichie, “The Danger of a Single Story,” July 2009, Oxford, UK, TED, transcript, 18:33, www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

[21]Adichie, “Danger of.”

[22]Adichie, “Danger of.”

[23]Diego Maggi, “Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied by an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’s Persepolis and Persepolis 2,” Journal of International Women’s Studies, no. 1 (2020): 89–105. Quote on p. 89.

[24]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 106.

[25]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 177.

[26]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 178.

[27]Farzaneh Milani, Words Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 231.

[28]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 5, 301, 333.

[29]Hamid Dabashi, Brown Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto, 2011), 23.

[30]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 19, 20.

[31]Nima Naghibi, Women Write Iran: Nostalgia and Human Rights from the Diaspora (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 107.

[32]Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[33]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 233.

[34]Naghibi, Rethinking Global, 141–46.

[35]Naghibi, Rethinking Global, 109.

[36]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 90.

[37]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 91, 92.

[38]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 166, 167.

[39]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 322.

[40]Amy Malek, “Memoir as Iranian Exile Cultural Production: A Case Study of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis Series,” Iranian Studies 39 (2006): 353–80. Quote on p. 369.

[41]Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 977.

[42]Satrapi, Complete Persepolis, 327.

[43]Said, Reflections, 174.

[44]Valentine M. Moghadam, Globalization and Social Movements: The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020), 164.

![“[Hamid Naficy] Self Portrait!,” 1996, Rice University.](https://www.irannamag.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3-3-4e-fig11.jpg)