Abbas Kiarostami’s “Lessons of Darkness”: Affect, Non-Representation, and Becoming-Imperceptible

In the total darkness, poetry is still there, and it is there for you.

-Abbas Kiarostami

I dream not of being invisible, but imperceptible.

-Gilles Deleuze

On July 4, 2016 when the world awoke to the devastating news of the passing of Abbas Kiarostami, many netizens, including the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, paid tribute to the late director by replacing their avatar on social media with a black screen. This “non-image” stood as a shroud of mourning, lamenting Kiarostami’s untimely demise, but it also contained within itself the very force of his cinematic art and pedagogy of the image. In his films Kiarostami gave us both lessons of silence and lessons of darkness,[2] communicating a different vision of cinema. His cinema often plays with withholding sound, visuals, and discernible forms, all of which otherwise would rely on representational models of recognition. Babak Tabarraee has previously expounded on a variety of auditory absences in Kiarostami’s “cinema of silence,”[3] and my intention here is to focus on visual absences, or black screen sequences, in such films by Kiarostami as Taste of Cherry (1997), The Birth of Light (1997), The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), ABC Africa (2001), and Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003). These black screen sequences are not simply extended structural cuts to black. Following Saige Walton’s conception of baroque cinema, they can be approached as folds, in which light is folded into darkness and darkness into light, not contrasted or opposed, but enmeshed and entangled. Walton explores the affinities between cinema and the baroque in her writings, finding inspiration both in Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the fold and Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notions of the flesh and the chiasm.[4] In particular, she analyzes baroque darkness, as found in Claire Denis’s films, describing it as ominous and threatening. As opposed to Walton and for my own purposes here, I will approach the modulation of darkness in Kiarostami’s films as vitalist, enabling, and liberating. To avoid sinister undertones, I will refer to the analyzed material as “black screen sequences,” not as “dark screen sequences.” In these sequences darkness acts as a camouflaged environment that takes us beyond established meanings, recognizable figures, and limits of perception.

In this essay I argue that the black screen sequences in selected Kiarostami films trigger a process of becoming-imperceptible through creative deterritorialization, transfiguration of surrounding environment, and transformation of registers of perception informed by habitual modes of living and being, including modes of institutionalized reception of images. These moments in his films encourage us to conceive of cinema not in terms of the passive reception of representation, based on the subject-object identification and the “dualism machines” of binary thinking,[5] but rather invite us to approach images through a non-representational lens. To facilitate the task at hand, this essay sets in motion a number of Deleuzian concepts that offer novel ways of engaging with cinema in a non-representational regime, such as “becoming-imperceptible,” “any-space-whatever,” “the fold,” and the “genetic power” of the black screen. As Brian Massumi famously observed, there is “no cultural-theoretical vocabulary specific to affect,”[6] and hence we could say the same of non-representation; however, Deleuze’s unique conceptualization of the world permits speaking nearby,[7] if not directly about, non-representation.

Non-representational theory gained momentum in the mid-1990s, originating from within the field of human geography, where it set about to describe embodied everyday practices of social life .[8] According to Phillip Vannini, non-representational theory is an experimental, nomadic, and non-dogmatic approach, engaged with works that aim “to rupture … and reverberate rather than report and represent.”[9] Often linked to the philosophy of Deleuze and Félix Guattari, it offers a much-needed break from the succession of “-posts,” but is still rather underdeveloped in terms of its methodology. Recently, such fields as art, philosophy, media theory, and film studies have also begun exploring the potential of “negative” prefixes, such as non-philosophy, non-photography, non-cinema, and non-representation.[10] As Gregory Seigworth observes, there is a tendency in affect studies to make use of such prefixes and “pre-” or “–non,” as in “pre-personal” or “non-representational.” With respect to the latter, however, it is important to understand that “-non” does not equal “anti-,” nor is it a negation or elimination; it is “not less.” Instead, the attention is shifted to “the ‘more than,’ the ‘other-than,’ the ‘different-than,’” or, in other words, “the saturating/magnetizing circumambience of everything,”[11] which destroys identity and imitation as such. In contrast to the legacy of structural, post-structural, and psychoanalytic models of analysis, heavily informed by the language of representation, meaning, and signification, these new approaches deal more with experience, emotion, and force of sensation. As Simon O’Sullivan aptly notes, this signals a shift from hermeneutics to heuristics, as a result of which an operative set of more familiar terms such as “representation,” “identification,” “subject” and “object” gives way to an alternative terminology of “movement,” “flux,” “assemblage,” and “transmission of affect.”[12] Such a turn in the cultural condition and visual regime underscores new modes of perception that offer unprecedented capacities and affordances for our emotional states.

“ [W]e see through a glass, darkly.”[13] The public has grown accustomed to the images of Kiarostami wearing dark glasses, even on the set of his films.[14] Kiarostami once confessed that he wore dark glasses both in public and in private for medical reasons: “The retina in my left eye has remained open, and no matter what I do it remains open, and it lets too much light in. I have no idea what happened.”[15] Such a medical condition might be considered a handicap for a filmmaker, but Kiarostami’s (im)personal vision of the world through dark glasses signals a change in habitual perception, an attunement to the unseen and the imperceptible. In answering the question, “What Is Baroque?” in The Fold, Gilles Deleuze observes that the art of the historical baroque announced a new age of light and color, one in which the worlds of light and shadows are separated by the thinnest of lines, however, not set in opposition but effectually enfolded. Specifically, he asserts: “This is a Baroque contribution: in place of the white chalk or plaster that primes the canvas, Tintoretto and Caravaggio use a dark, red-brown background on which they place the thickest shadows, and paint directly by shading toward the shadows.”[16] Kiarostami’s practice of filming through dark glasses, his heightened sensitivity to the indiscernible, can be read as analogous to the Baroque artists’ application of a dark background instead of a white primer for their canvases. In this manner, that which would normally be obscured or overlooked in contrast to brighter figures is now engaged in the dynamic interplay of light and darkness, if not necessarily in equal measure. Kiarostami’s own photosensitivity demands that we reach outside of normative subjectivity and switch our registers of perception from representation to non-representation.

Image 1: Abbas Kiarostami wearing dark glasses in the final scene of Taste of Cherry

Kiarostami’s black screen sequences have been addressed before as part of an analysis of separate films, but not in comparison to one another as a unique characteristic of his cinematic style.[17] In many of the black screen sequences under consideration, feeble sources of lighting and dark shadows obstruct representational content, focusing on the material plane of the image and inviting the force of sensation rather than offering any form of signification. The low-light conditions reduce cinema to its essential resources of light and movement, so that “cinema is … distilled as an aesthetic that relies less upon light and more upon dark.” These types of “sunless images,”[18] according to Nadia Bozak, are dependent on “withholding light sources and thus foregrounding how the constant availability of this cinematic ingredient has become naturalized as part of viewing expectations.”[19] Despite their apparent minimalism, however, Kiarostami’s black screen sequences are incredibly rich. For example, one can trace a variety of light sources in them, whether natural or artificial. There is a gradual switch from the prolonged darkness of night to the first rays of solar light at the end of The Birth of Light and Five; lunar light is present in Taste of Cherry and Five; and we see flashes of lightning in ABC Africa, Taste of Cherry, and Five. In addition to natural atmospheric light, artificial light sources include a lantern (Where the Wind Will Carry Us); a lighter and car headlights (Taste of Cherry); a flashlight, hotel floodlights, and matches (ABC Africa). As Bozak states, the history of cinema can be traced to the energy of the sun, which is “the heart of cinema, its fuel and perhaps even its spirit.”[20] In the course of its development cinema depended on both outdoor sources of light as well as artificial light: “The cinema originated, at least in part, within the same imagination as the electric light bulb.”[21] So the condition for the appearance of images and cinematic technology in general lies in the interrelation between natural and artificial light. But as Bozak further observes, even though the cinematic image relies on the availability of light, it also requires darkness as the condition of its emergence.[22]

There is a characteristic switch from darkness to light, night to day, and death to life that is traceable in all the black screen sequences. Henry Corbin once called the twilight, a common motif in Iranian poetry, a moment of “in-between, where one side looks towards the brightness of day, and the other side towards the darkness of night.”[23] Importantly, Kiarostami does not set darkness and light in opposition but rather explores their interrelation as a creative interplay of folding and unfolding matter that gives birth to images. Deleuze suggests thinking of the fold in connection to Heidegger’s concept of “Zweifalt, not a fold in two … but a ‘fold-of-two,’ an entre-deux, something ‘between’ in the sense that a difference is being differentiated.”[24] We can only think of darkness through light, death through life, non-representation through representation (and vice versa) in the moments when the two intersect, intermingle, bend, and re-fold: “Non-representational theory needs ‘a hinge-logic, a hinge-style.’”[25] Darkness and light, black and white act as the genetic forces of cinema, providing material out of which the visible appears and into which it recedes. Deleuze holds that the genetic power of the black or white screen in time-image cinema “restor[es] our belief in the world,”[26] invoking the Nietzschean concept of an eternal return to origins for renewed value. The energy of the sun acts as a source and force of not only images but also life in general: “sun makes the world visible,” but it also “makes it possible.”[27] In Kiarostami’s films, all moments of darkness end with an affirmative gesture of the “birth of light,” suggesting that life regenerates itself and goes on: “[a]s long as there is sun, the earth’s fossil fuels could in fact be renewed.”[28]

Darkness also acts as a fuel: it becomes a driving force for the viewer’s imagination. Kiarostami’s unfinished cinema retains its secrets because it “requires gaps, empty spaces like in a crossword puzzle, voids that it is up to the audience to fill in.”[29] Because this is an experience at the limits of perception, the rarefied sensory-motor aspect is driven to connect with the affective and cognitive modes. Many of Kiarostami’s films produce new visions for possible becomings, such as a becoming-woman, a becoming-animal, a becoming-minor, and a becoming-molecular, which run counter to traditional structures of the visual world. “Becoming,” a pivotal concept in this discussion, is regarded by Deleuze and Guattari as a constitutive process of existence, the condition of continuity and sustenance of life. Becoming is not about imitation or identification but about transformation and change. Deterritorialization through darkness in particular involves a becoming-imperceptible, the ultimate chain in a flow of becomings. Deleuze and Guattari describe it as a type of perception that no longer pertains to the subjective-objective view of the world (which could serve as a capsule definition of representation), but approaches life in the context of non-personal affect and intensity, which is inherently non-representational. Imperceptible does not necessarily mean invisible: rather it is a stage (but not a state) in which perception becomes molecular, when we “arrive at holes, microintervals between matters, colors and sounds engulfing lines of flight, world lines, lines of transparency and intersection.”[30] As Simon O’Sullivan observes, art can reveal “other ‘planes’ of reality” that may become discernible through changing temporal and spatial registers.[31] Abbas Kiarostami is often described as a filmmaker who does not engage in manipulating the medium. But in what follows I show that Kiarostami points to the imperceptible by relying specifically on the prosthetic technology of cinema, sometimes under the guise of darkness. By mobilizing our perceptual fields in an attempt to address and renew the very limit of what is perceivable, the black screen sequences in Kiarostami’s films bring into the open the degree to which we are caught in the flow of habitual and deep-seated perceptions.

The Meeting of the Wind and the Leaves: Poetry, Secrets, and the Darkness of the Screen-Cave

The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) takes place in the Kurdish village of Siah Darreh, or “Black Valley,” where a crew of filmmakers has arrived to record the mourning rituals for the local centenarian, a woman who has stubbornly refused to die on cue. The man in charge of the crew, Behzad (Behzad Dorani), observes a young woman from the village bringing fresh milk to a well digger, Yossef, a man burrowing deeper into the valley. Behzad is determined to follow this fresh milk to its source. First directed to “Kakrahman’s house,” Behzad is then shown into a dark cellar, stooping beneath the low ceiling and carrying his milk pail. He is a disbeliever, uninitiated in local rituals: “Why is it so dark here?,” he asks, hesitating on the threshold. As he moves forward, he advances on the camera position until his own body blocks the remaining light from the low door—most likely, an invisible cut[32] occurs here, and the screen goes completely black for several seconds.

(Image 2: Zeynab is milking the cow in The Wind Will Carry Us)

Behzad has entered a pitch-dark cellar, with only the sounds of his tentative footsteps, the bleating of a goat, and the lowing of the cow to orient the viewer. Miss Zeynab appears out of the darkness carrying a hurricane lantern, which does not illuminate the girl’s face throughout the scene of the milking which follows. Behzad is reminded of the opening lines of Forough Farrokhzad’s poem, “Gift” (Hediyeh): “I speak out of the deep of night / Out of the deep of darkness / And out of the deep of night I speak,” as he is suddenly inspired to recite the second stanza of the poem.[33] Taking Zeynab by surprise, he declares, “If you come to my house … Oh, kind one, bring me the lamp and a window through which I can watch the crowd in the happy street.”[34] After asking Zeynab’s permission, Behzad then recites to her another of Farrokhzad’s poems, “The Wind Will Take Us,”[35] which lends the film its title. In his reading of this scene, Hamid Dabashi regards the recital of Farrokhzad’s poems in the darkness of the cellar as that of “a vulgar man intruding into the private passions of a young woman.” He also calls the milk “a substance with mischievously sexual connotations” and notes that “the protagonist leaves with a bucketful of milk and a satisfied grin on his face,” condemning the whole scene as “ocular masturbation.”[36] He concludes, hyperbolically, that the “stable sequence is one of the most violent rape scenes in all cinema.”[37] Dabashi’s emphatic interpretation of the scene has been met with some apprehension, and a few film critics, such as Joan Copjec and Chris Lippard, offered alternative readings of this poignant moment in the film. In contrast to Dabashi, whose attention was focused on the male figure (it is notable that he never identifies Zeynab by her name, referring to her only as a “milkmaid”),[38] Copjec shifts the emphasis from Behzad’s shameless behavior to “the awakening of shame in Zeynab,”[39] who “requires an intervention, the presence of others as such, in order to emerge from the milking, from the gerundive form of her impoverished existence, as a subject.”[40] This approach itself is an important feminist intervention of reading from a woman’s point of view, illustrating the impact of a female character who is placed in a more active subject position. Copjec continues, “In Dabashi’s reading of the encounter between Behzad and Zeynab, it is Behzad who brings shame to Zeynab. This misreading depends on the reduction of shame to the product of a simple intersubjective relation in which the belittling or degrading look of another person is sufficient to ignite shame. I would argue, however, that it is not Behzad who occasions shame in Zeynab, but the erotic poem by Forough Farrokhzad, ‘The Wind Will Carry Us.’”[41] Two important observations by Copjec invite another reading, one that transcends the subject-object relationship. My Deleuzian approach to this scene draws inspiration from an affective encounter that takes place in the darkness of the cave and poetry as a deterritorializing creative force.

Dabashi’s representational analysis is deeply locked within the subject-object position (a brutal man “raping” a helpless milkmaid) and is, most likely, informed either consciously or unconsciously by his knowledge of the peculiar system of codes in Iranian cinema. As Copjec and others explain, the system of sartorial modesty, or hejab, is quite pervasive in Iranian culture. Its influences can be traced in cinematic representations after the Iranian revolution, which dictated that female characters had to remain veiled in the presence of their onscreen husbands (and also, by extension, the off screen male spectators).[42] As bodies and feelings had to be cloaked, “[p]oetry became the only option for expressing intimacy, at first primarily for the men.”[43] For example, in his analysis of Rakhshan Banietemad’s The May Lady (1998), Hamid Naficy describes an exchange between Foruq, whose name is a nod to Forough Farrokhzad, and Mr. Rahbar, who “exchange letters and, using one of the favorite Iranian devices of intimacy, sexuality, and love, quote poetry to each other.”[44] In trying to find the key to the cryptography of the scene, Dabashi interprets the recital of the poem solely as a means of indecent and immoral seduction. But rather than portraying the scene as unbecoming, I propose instead that it invites multiple becomings.

“You’ll get used to it if you stay here,” says Zeynab to Behzad, for whose benefit she has lit the hurricane lantern. He replies, “I’ll be gone before I get used to it.” For both Behzad and Zeynab, this encounter offers a new connection, another relation to the world other than the one they are used to. Behzad descends into the cellar from the sunlit world outside, while Zeynab spends her days in the dark. They both momentarily undergo a reaching out to something that is outside of their habituated experience, an “experimental milieu” outside of their normal selves .[45] The habitual modes of their existence are interrupted by an affective moment in the cellar, where a switch in perceptual orders takes place. For Behzad, the darkness of the cellar and Zeynab, the keeper of its secrets, exist on a different perceptual register. For Zeynab, the stranger’s presence interrupts her existence through the light of the lamp cast on her while she is milking. The poem Behzad recites brings her a “window” into the world through which she can “watch the crowd in the happy street” out of her windowless cellar. “The wind is about to meet the leaves,” continues Behzad and, after a pause, he explains this line to Zeynab: “the two are meeting.” He tries to find a more accessible way to explain the affective power of poetry through language that would be understandable to Zeynab and adds, “It’s like when you went to see Yossef” (who likewise spends his days in the dark and whose face we never see). This scene, however, is not just about an ordinary meeting between Zeynab and Yossef, or Zeynab and Behzad; rather, it is an encounter with an asubjective power of affect. As O’Sullivan points out, “affect is a more brutal, apersonal thing. It is that which connects us to the world. It is the matter in us responding and resonating with the matter around us.”[46] The meeting of “the wind and the leaves” in the darkness of the cellar affects both Zeynab and Behzad, inviting becomings. This affective desire is “connected to the feminine, defined as fluidity, empathy, pleasure, non-closure, a yearning for otherness in the non-appropriative mode, and intensity.”[47] For both Behzad and Zeynab, it starts with an opening to a becoming-woman. Behzad steps into the zone of dark quarters occupied by Zeynab, and Zeynab, who went to school approximately the same number of years as Forough, “becomes-woman” through and with her poetry.

Kiarostami urges us to look for poetry even (and especially) in complete darkness. In her illuminating study Khatereh Sheibani describes the influence of modern Persian poetry on Kiarostami’s filmmaking. In her discussion of the film The Wind Will Carry Us, Sheibani observes that “the concept of binaries, which suggests a fixed-reality scheme through which many of us perceive the world, is problematized” here.[48] The film invites an overstepping of the “black and white” alternatives,[49] or for that matter the urban and rural, above and below ground, life and death, male and female, and subject and object pairings. The film abjures these “rationalizing” linguistic patterns in favor of the assemblage of disparate expression, “this way or that,” “both good and bad,” that can be found in the poetics of Farrokhzad and Sohrab Sepehri.[50] In their discussion of becoming-music, which can also apply to lyric poetry, Deleuze and Guattari remark that “musical expression is inseparable from a becoming-woman, a becoming-child, a becoming-animal” because it participates in a form of “creative deterritorialization.”[51] Zeynab is (in)visibly affected by Forough’s lines. Unlike in the classic affection-images (the close-ups of Joan’s face) in Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928),[52] we are unable to see the traces of affect on Zeynab’s face, as it is obscured by darkness. We can only sense her affect, as her re-action is suspended and remains non-actualizable, in a state of virtuality and potentiality. Male and female, subject and object, voyeur and observed are swept up in the creative deterritorialization of poetry.

Dabashi considers the scene an obscenity, but it is only because he is examining what is perceptible to the voyeur. Instead, this scene invites us to explore the process of becoming-imperceptible, through the pathways of poetry and secrets. Deleuze and Guattari suggest that the “secret has a privileged … relation to perception and the imperceptible.”[53] The secret issues an invitation to becoming-imperceptible, though it may do so in part through what it reveals as much as through what it withholds, in its form and in its content. To Behzad and the spectator, Zeynab remains a secret, an enigma: “The protector of the secret is not necessarily in on it, but is also tied to a perception, since he or she must perceive and detect those who wish to discover the secret.”[54] The choice of a dark cellar in this film, as well as the choice of a grave in Taste of Cherry is quite notable. Both, as subterranean grounds, offer a tangibly material contact with the earth’s innards. A meeting point between the Cosmos and the Brain, caves have taken center stage in many religions and philosophies. Yulia Ustinova connects the importance of caves in ancient Greece to the recent findings in neuroscience, building on the concept of altered consciousness. According to her, the descent into a dark cave (catabasis), immersing oneself in a state of sensory and significatory deprivation, provided a path to the ascent (anabasis) of the mind.[55] As Ustinova also observes, “[c]aves hid awe-inspiring secrets and treasures.”[56] The prehistoric caves of Lascaux, the underground spring of the ancient oracle at Delphi, and even a rough-hewn cellar in a remote Kurdish village—such underground precincts hold hidden secrets and mysteries precisely because they are sealed off from the perceptible world. The secret remains hidden in the dark, the unseen, the becoming-imperceptible, for those who seek it. It is not too much, perhaps, to suggest that at the same moment in which Behzad and the viewer enter the realm of darkness, he/we experience an altered state of consciousness, as the mind lets go of its dependence on habitual vision and the appearance of things. But if for Behzad the reaching out to an “experimental milieu”[57] outside of himself is triggered by his passage into a dark space, for the spectator this happens through recourse to the “experimental night”[58] that cinema spreads over us, thereby affecting “the visible with a fundamental disturbance, and the world with a suspension, which contradicts all natural perception.”[59] This scene prompts us to put normative perceptions and expectations into flux, distorting the habitual cinematic codes that usually rely on visibility and audibility. For the spectator, becoming-imperceptible is not about disappearance but about reconstituting the nature of one’s perceptual field and changing the threshold of the perceivable world. The secret of the scene in the dark cellar lies in “a perception that seeks to be imperceptible itself”[60]: “Listen / Do you hear the darkness blowing?”[61]

Modification of Speeds I: Drugs and the Darkness of the Screen-Grave

The critical response to Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (1997) has emphasized its minimalist techniques, often at the expense of its vision, including its long, uninterrupted takes, lack of apparent action, long shots that encompass a barren landscape, and extended durations without dialogue.[62] For most of the film Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) drives through Tehran and the surrounding countryside in zigzagging patterns seeking an accomplice for his planned suicide. This departure from the Hollywood action film model led critics such as Roger Ebert to declare the film “excruciatingly boring,” because from the perspective of western feature cinema, there was almost nothing to see.[63] What Ebert fails to see are the imperceptible changes: each time Badii travels to the same spot with a pre-dug grave and a tree next to it, he undergoes a series of transformations, not unlike Behzad in The Wind Will Carry Us. Behzad also repeatedly drives up the winding road to the top of the hill (where the cemetery is located) in search of a signal whenever he receives a call from his Tehran boss. Even though the route is repeated, it is never the same journey for either Behzad or Badii. Every time they come to “the same” location, they arrive there in a renewed state, transformed by a series of affective encounters with the villagers (Behzad) or the car passengers (Badii).

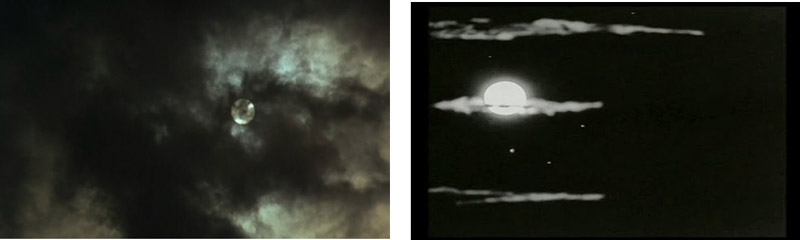

The final sequence of the film, after Mr. Badii has recruited an Azeri taxidermist to throw earth on his body if the latter finds him dead in the morning, demands a changed perspective. First, we watch Mr. Badii from a distance moving from one room to another in his apartment. He appears to take into his mouth what we can only infer is an overdose of sedatives or some other drug. Then, under the guise of night, the taxi with Mr. Badii in it heads on a zigzagging path up the hillside to the spot of the open grave. If we look at the scene in a planar dimension, instead of inferring three-dimensional space, then what might be a pair of headlights presents a folded line of flight in the dark with relation to what might be a scattering of streetlights or lit domiciles. Without the changed perspective of holes in space or lines of transparency, without drawing our attention away from the world of perceivable objects and toward the molecular realm of becoming-imperceptible, we cannot appreciate what is about to transpire at the gravesite. We next see the seated Mr. Badii with his back to the fixed camera, framed against the darkened landscape just described. He smokes his “last” cigarette after fighting with his lighter, which stubbornly refuses to work. He then takes his position inside the grave waiting for the drugs to take effect. Drugs of various sorts can be inducements to altered consciousness, “All drugs fundamentally concern speeds, and modifications of speed. What allows us to describe an overall Drug assemblage in spite of the differences between drugs is a line of perceptive causality that makes it so that (1) the imperceptible is perceived; (2) perception is molecular; (3) desire directly invests the perception and the perceived.”[64] The face of Mr. Badii, recumbent in his shallow grave, is momentarily illuminated by the moon and then obscured by the clouds passing above him, lit by a flash of lightning and then cast into a blackout that, in screen time lasts for over a minute but, as Mr. Badii passes into the imperceptible, unfolds for an eternity. As Rosi Braidotti poignantly intones, “What we most truly desire is to surrender the self, preferably in the agony of ecstasy, thus choosing our own way of disappearing, our way of dying to and as our self. This can be described also as the moment of ascetic dissolution of the subject; the moment of its merging with the web of nonhuman forces that frame him/her—the cosmos as a whole.”[65] The prolonged blackout will be irritating to those who wish for only the conventionally perceptible in cinema, to know “what happened.” But for those more conducive to a changed perspective, it invites us to an experience of becoming-imperceptible in the disappearance of the subject, the collapse of the subject-object dichotomy.

(Images 3 and 4: The obscured moon in Taste of Cherry and Un Chien Andalou)

The effect of the blackout, the obscuring and eclipsing of light, recalls the famous play on cuts in Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), when thin clouds are passing in front of a full moon and a straight razor is drawn across a woman’s wide-opened eye.[66]

In Taste of Cherry we hear the sound of distant thunder and in the split second of the lightning flash, we can see that Mr. Badii’s eyes have closed. The extended black screen, or cut, is simultaneously the occluded moon, Mr. Badii’s shut eyes, his presupposed diegetic passing, and our experience of the darkened theater in which we view Taste of Cherry.[67] But the imperceptible cut that takes place here suggests that the black screen is not simply a “symbol” of death or an “emblem” of a funereal cloak. As darkness comes to its end, we first hear and then see—but in the differing vision and framing of video—a troop of soldiers marching along the winding road in full daylight. It is not the morning after, or the arrival of the taxidermist, but a completely different season and a grainier camcorder footage of Kiarostami, Homayoun Ershadi,[68] and the film’s crew and cast, shooting scenes or relaxing between takes, as the soundtrack introduces Louis Armstrong’s jazz dirge, “St. James Infirmary Blues.” If the latter seems culturally disparate, it is a funeral march that celebrates life rather than mourns death. As Deleuze claims, “Becoming imperceptible is Life, ‘without cessation or condition’ … attaining to a cosmic and spiritual lapping.”[69] The videotape coda is an assertion that for the past ninety minutes we have been watching not an act of self-annihilation but of creative deterritorialization, one that affirms life on the plane of immanence. Nagisa Oshima once said of his method of banishing green, “No matter how severe a human confrontation you are portraying, it immediately becomes mild the instant that even a little green enters it. Green always softens the heart.”[70] The switch from a barren landscape to a scene with bright greenery promises regeneration and rebirth. The extended black screen, then, serves as a “fold-of-two,”[71] as the processes of life and death are materially enmeshed together rather than separated in the either/or of the “dualism machine.” An invitation to becoming-imperceptible is achieved through the treatment of the medium itself, in which the cut from 35 mm film to videotape not only transfers and enfolds the two media within one another but the two ontological registers as well. The black screen is neither erasure nor negation but the locus of an encounter. There is no cessation in the flow of matter, but rather a fold of two world lines, the intersection of which situates itself in the realm of the imperceptible and explored through the very materiality of the medium. As spectators, we reach this creative deterritorialization of seemingly opposed states of life and death, disparate media, and levels of ontology through the imperceptible blackout that they share.

Modification of Speeds II: Time-Lapse Effects and Any-Space-Whatever

The short film The Birth of Light (1997) and the documentary Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003) eschew conventional narrative development and typical character representation. Instead, the attention in both films is shifted to alternative planes: animal, inanimate, molecular (a becoming-dog, a becoming-duck, a becoming-wood, a becoming-wave). They also invite us to explore the threshold between the perceptible and the imperceptible. The Birth of Light and the final section of Five emerge from a primordial darkness into the first emanations of light. The initial darkness in The Birth of Light, first through a thin ray of light that becomes stronger, transforms into dawn as the sun rises over the distant mountains. The short film was commissioned by the Locarno International Film Festival, with photography by Bahman Kiarostami and music by Peyman Yazdanian. Rumor has it that it might have been intended for inclusion in Lumière and Company (1996), an anthology of films by international directors who were encouraged to use the vintage Cinématographe of the Lumière brothers to commemorate the centennial of motion pictures.[72] One might be tempted to explore the link between the birth of cinema and the birth of light (lumière); however, the film is not in black-and-white, but in color, and much longer than the anthology’s required fifty-two seconds. Curiously though, two aspects of this short film link it to Kiarostami’s final film-compilation, 24 Frames (2017), alternatively known as 24 Frames Before and After Lumière. The Birth of Light runs just under five minutes, which is approximately the time (about four-and-a-half minutes) of each segment included in the compilation. In addition, both projects examine the boundary between still and moving images, real and artificial, manipulation and non-manipulation. If the still images in 24 Frames, mostly personal photos by Kiarostami, come to life through imperceptible digital techniques, The Birth of Light relies on a time-lapse effect, animating a seemingly static image of the mountain landscape.[73]

Five, also known as Five Dedicated to Ozu, is an ensemble of non-narrative shorts. In Five (as well as in The Birth of Light and 24 Frames) Ozu’s “pillow-shots”[74] become extended meditations on backgrounds, which come to the fore in a non-representational style. According to Vannini, backgrounds are the “sites that fall outside of common awareness, the atmospheres we take for granted, the places in which habitual dispositions regularly unfold.”[75] In these films Kiarostami abandons representational dramas of the foreground in favor of the backdrops that often pass unnoticed. The segments in Five are separated by black or white screens overlaid with music, which are ontologically different (as straightforward structural cuts) from the final black screen sequence. This section is the longest and runs to nearly thirty minutes. It begins in total darkness, and then light is gradually reflected on shallow, dappled water, appearing and disappearing into darkness again. The wind susurrates, a thunderstorm brews and raindrops splash on the water’s surface, frogs croak and waterfowl squawk. Or so it seems, with a sort of Zen consciousness and placidity that we could ascribe to Ozu. But like the planar screen that we observed in Taste of Cherry, the image is so rarefied and difficult to discern that we become aware that we are watching the projection of light and not (only) observing a contemplative nature-scape. The liminality between the imperceptible and the perceptible is at issue here, defined in Deleuze and Guattari as “zones of indiscernibility”: “The Cosmos as an abstract machine, and each world as an assemblage effectuating it…. To be present at the dawn of the world. Such is the link between imperceptibility, indiscernibility, and impersonality—the three virtues. To reduce oneself to an abstract line, a trait, in order to find one’s zone of indiscernibility with other traits, and in this way enter the haecceity and impersonality of the creator.”[76]

(Image 5: Light reflected on the water’s surface in the final segment of Five)

The impressionist appreciation of what appears to be a single long take—perhaps so long as to try the patience of the distractible filmgoer, and indeed Five also doubled as a gallery installation piece—was “achieved only after filming several ponds over an extended period.”[77] This segment is an artfully composed montage, painstakingly achieved through the manipulation of the shot(s), concealing the edits in what appears to be the diegetic blackness of the screen. We are led to believe that the light of the moon reflected on the surface of the pond is eclipsed by the passing clouds as we are plunged into complete darkness. But as we saw in Taste of Cherry and Un Chien Andalou, it might be just a subtle nod to the cinematic cut. Like the dawning in The Birth of Light, the muted grays, low contrast, and barely discernible surfaces are eventually tinged by Homer’s “rosy-fingered dawn” and the crowing of a cock. The appearance of such “naturalness,” however, is only arrived at through the technical manipulation of film, the use of time-lapse montage.[78] As discussed earlier, one entrée into the virtue of imperceptibility is speed. Just as drugs affect humans in various ways, speeding up or slowing down bodily functions (Mr. Badii who takes his sleeping pills), the effects of modifying of speeds, such as time-lapse, high-speed, or slow-motion effects, change the metabolism of cinema. It only takes about “five minutes” for the darkness to be transformed into light in The Birth of Light. In time-lapse cinematography, the frame rate is lower than the speed used to watch the sequence, so that the processes that would appear imperceptible to the human eye can become perceptible. Deleuze and Guattari tell us, “Movements, becomings, in other words, pure relations of speed and slowness, pure affects, are below and above the threshold of perception. Doubtless, thresholds of perception are relative…. What we must do is reach the photographic or cinematic threshold … according to variable speeds and slownesses.”[79] The becoming-imperceptible is all around us; it is, among other things, happening at speeds that are either above or below the threshold of human perception: the geologic time of continental drift or the beating of a hummingbird’s wings; or, the rotation of the planet that brings dawn and dusk each day. The kino-eye, as demonstrated throughout the manipulation of frame rate, grants the spectator an entrance into the imperceptible.

The black screens in The Birth of Light and Five are instances of what Deleuze describes as the rarefaction of the image (“less information”), in which little or no light penetrates and observable objects are minimal or few.[80] Blackness and whiteness can be conceived—cosmically and cinematically—as either the fundamentals out of which all the stuff of the world begets or the elementals into which it disintegrates. In Kiarostami darkness is not negative, but enabling, and the vitalist forces always prevail. In both films, a new day arises out of the darkness of night, a characteristic of Kiarostami’s themes of birth, death, and regeneration. Deleuze references the concept of any-space-whatever in his descriptions of the affection-image of classical cinema as well as in the depiction of the movement-image crisis and time-image films. Extending as far as the void, these any-spaces-whatever manifest their genetic power: “Nothingness itself is diverted towards that which comes out of it or falls back on it, the genetic element, the fresh or vanishing perception.”[81] No coordinates can be assigned to these spaces, instead, they exhibit independent qualities and forces outside of belonging to any actual locations.[82] Famously, Deleuze describes Joris Ivens’s Rain (1929) as no longer a direct representation of any concrete rain, but a qualisign, a pure quality of rain as an affective state achieved through an accumulation of images in rapid montage.[83] In the last segment of Five the rain abruptly begins and ends, and there are irregular flashes of lightning, illuminating the black screen, not unlike irrational cuts in experimental flicker films, which render the space in a fragmented and disconnected manner. Kiarostami’s waterscape, as any-space-whatever, is not any localizable basin of water, but a space of virtual dimension, deterritorialized and indeterminate. As affect overflows the frame, it becomes a “pond of matter in which there exist different flows and waves.”[84]

“The Electricity is Off”: Power Cuts and Any-Space-Whatever in Minor Cinema

Kiarostami’s documentary film, ABC Africa (2001), was made at the invitation of the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development. The director and his assistant, Seifolah Samadian, travel to Uganda, where they spend ten days recording digital video of the many children orphaned by AIDS and warfare, being cared for by the Uganda Women’s Effort to Save Orphans. One night, as Kiarostami and his assistant discuss the day’s shooting, they observe a swarm of mosquitoes around the hotel’s floodlights. As soon as they are told that the electrical power will be cut off by the local authorities at midnight, they (and we) are immediately plunged into darkness.[85] We are reminded of the moment in The Wind Will Carry Us when Behzad finds himself in complete darkness in the cellar, and in response to his bewilderment, Zeynab explains, “We have a flashlight. The electricity is off.” In a rural Kurdish village, episodic power outages might be a fact of life. For the cosmopolitan Tehrani Behzad, however, darkness disrupts habitual systems of sensory perception as he struggles to acclimate himself to an utterly different mode of existence. When Kiarostami and his assistant find themselves in a similar situation in Uganda, they are equally unable to cope, nor have they brought a flashlight as recommended by the authorities: “How can they live in this darkness?,”[86] they ask each other. The videorecording rolls for another seven minutes in the dark as the filmmaker and cinematographer attempt to find their way by a single matchlight and, eventually, flashes of lightning through the window. For a filmmaker reliant upon the electrical grid for production, and with light being the constituent medium of cinema, the unexpected power loss is profound. They observe of the locals, “The sun is gone, life is gone,” but they could equally be speaking of their own work. “With no candles, no lights, no television and no internet [and we could add, no cinema]. I can’t think of anywhere in this world where the sun could be more precious and welcome,” they say, referring to Ugandans. In Bozak’s words, during this moment we get a glimpse into the “privileged world without its natural mechanisms of power and structure … deprived of its electrical supply.”[87]

(Image 6: The matchlight in ABC Africa)

Kiarostami makes us aware of how much we rely on the habituation of our motor-sensory faculties to carry ourselves through our daily (and nightly) activities. When any one of those faculties is disturbed, we are paralyzed, fixed in place like a bat suddenly unable to echolocate its position in a cave. Groping in the dark, Kiarostami and his assistant continue conversing, “They live half their lives within these dark walls, like blind people. We can’t even handle five minutes of it.” But, of course, it is not only the director and the cinematographer who are deprived, we, the spectators in the theater, or perhaps streaming this sequence on our laptops, likewise feel unable to handle five minutes of the black screen—a veritable eternity in our habituation to an ever-flickering image—so that we experience something like anxiety, claustrophobia, or simply displeasure. The black screen presents itself against naturalized systems of representation, defamiliarizing “the privileged viewing conditions that ‘institutional’ (from [Noël] Burch) or ‘state’ (Deleuze) viewership takes for granted.”[88]

Kiarostami’s cinema has been previously placed under the rubric of Deleuzian “minor cinema” in connection with new political forms of consciousness.[89] In this sense, Kiarostami, an Iranian filmmaker, undermines the dominant Hollywood “language” through his “accented cinema,”[90] much like Kafka, writing in German as a Jew living in Prague, and creates “lines of flight” by way of experimentation.[91] The black screen in ABC Africa, similar to that at the end of Five, can also be approached as an any-space-whatever. For one, there is the shared motif of lightning strikes that make the screen appear and disappear out of the throbbing darkness, thus fragmenting the space. But, poignantly, in minor cinema these spaces of virtuality, invisibility, and affect also become the locus in which “the missing people are a becoming,” they create their collectivity and “invent themselves”[92] in the absence of recognition in the black tunnels and the underground into which they were pushed by power structures. For these “missing people,” either the Kurdish milkmaid Zeynab or the Ugandan grandmother who cares for thirty-five children in a single room, the power failure might be caused either by poor infrastructure or by political struggles. The “voided” nature of the spaces where the missing people find themselves has a strong genetic element, which in minor cinema acquires the special meaning of an anticipatory function, the seeds of the people to come. These “disconnected spaces”[93] (from electricity and privilege) become emancipatory channels, a call “for a future form, for a new earth and people that do not yet exist.”[94] And if there is hope for humanity, then it will be because the privileged, sunstruck cosmopolite Behzad, a cognate of the film director, will acclimate himself to the motor-sensory deprivation of the dark cellar, thus “becoming-woman,” “becoming-molecular,” “becoming-imperceptible,” just as Kiarostami and his assistant will also see in the lightning-illuminated trees of Uganda their own “becoming-other,” “becoming-minor.” There is also hope for the spectator who will reach out to the imperceptible and co-emerge with the world through the affective power of darkness and for whom the non-signifying black screen will become a virtual space where new possibilities can be thought. But above all, there is hope for all people who will engage with the Earth differently.

Coda

In this essay I address the deep affinities between Deleuzian philosophy and Kiarostami’s films, placing the latter’s cinema within the recent turn to non-representation, affect theory, and the reframing of regimes of visuality in film-philosophy and media theory. I argue that Kiarostami’s cinema, especially his black screen sequences, aspire to the logic of non-representation in the audiovisual medium of cinema, which so willingly succumbs to the tenets of mimesis. The sequences of darkness in Kiarostami’s films invite an imagination of baroque interiors characterized by folds within the intersection of light and shadow, allowing entry into the realm of the imperceptible. Many of Kiarostami’s seemingly uninterrupted and non-manipulated shots mask elaborate labor, capturing movements invisible to the human threshold of perception, which in the black screen sequences is aided by darkness. As Ahmad Kiarostami noted during the post-screening conversation about 24 Frames at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, in many of his father’s films, what you see and take for granted has been in fact painstakingly constructed. It should not come as a surprise, then, that in Kiarostami’s last film, 24 Frames, “everything is very carefully designed” by means of digital manipulation.[95]

24 Frames, a reference to the twenty-four frames per second at which film is projected, was shown posthumously at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival. The film was inspired by Kiarostami’s desire to know what comes “before” and “after” each given image. Recalling Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotic concept of “thirdness,” which splits the binary of the signifier/signified,[96] there has always been an indiscernible twenty-fifth frame in Kiarostami’s cinema, an element outside of the system of signification, which compels the viewer to reach beyond the dimensions of narrative content. The final black-and-white frame in 24 Frames depicts a young woman sleeping in front of the big window, with her head on her desk. On the computer screen beside the woman is a scene from the classical Hollywood film, William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), which portrays a kissing couple. Famously, Kiarostami did not object to spectators sleeping during his films and even encouraged them to do so: “dreams are windows in our lives, and the significance of cinema is in its similarity to this window.” He emphasized that it was more important how the spectators felt after the film, and he wanted them to experience a “relaxing feeling” following the film’s end.[97] We then hear Andrew Lloyd Weber’s song, with lyrics by Glenn Slater, “Love Never Dies”: “Love never dies once it is in you / Life may be fleeting, Love lives on.” Finally, “The End” flashes on the computer screen, depicted against the background with streaks of light and shadow. The credits start rolling to the side of the frame, announcing Abbas Kiarostami as the director of the film. The twenty-fourth frame is a folded farewell that finds itself betwixt and between the happy ending of the classical movement-image cinema and the time-image cinema’s unresolved closure. “Nothing is ever finished in [Kiarostami], nothing ever dies,”[98] and thus there is no END in his open-image cinema. We walk away tranquil and unhurried, but now it is up to us to open that window into our individual lives and unravel what comes “after” the final frame, to track the course of Life in its reverberating process of growth and change. Kiarostami’s cinema demonstrates an affirmative ethics that helps us to survive and sustain ourselves against all odds: there is the birth of light and continuance of life on earth, even in the face of death. It’s Life, And Nothing More…

![(Image 7: “The End” frame from William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives [1946])](https://www.irannamag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/fig7.png)

(Image 7: “The End” frame from William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives [1946])

[2]I am alluding here to Werner Herzog’s documentary, Lessons of Darkness (1992) of burning oil fields in post-Gulf War Kuwait, but not in any overtly political sense, nor in an apocalyptic manner. Lessons of Darkness, directed by Werner Herzog (France, Canal+, 1992), Film.

[3]See Babak Tabarraee, “Abbas Kiarostami: A Cinema of Silence,” Soundtrack 5, no. 1 (June 2012), 5-13, and also his MA thesis, “Silence Studies in the Cinema and the Case of Abbas Kiarostami” (Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, 2013). Kiarostami’s cinema has also been described as “cinema of questions,” “delay and uncertainty,” “ellipsis and omission,” cinema of an “open image,” and “unfinished” or “half-created cinema.” See Godfrey Cheshire, “Abbas Kiarostami: A Cinema of Questions,” Film Comment 8, no. 6 (July/August 1996): 34-36, 41-43; Laura Mulvey, “Kiarostami’s Uncertainty Principle,” Sight and Sound 6 June 1998, 24-27; Saeed-Vafa Mehrnaz and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2003); Shohini Chaudhuri and Howard Finn, “The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema,” Screen 44, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 38-57; Abbas Kiarostami, “An Unfinished Cinema,” Text Written for the Centenary of Cinema, distributed at Odon Theatre, Paris, 1995; and Mohammad Jafar Yousefian Kenari and Mostafa Mokhtabad, “Kiarostami’s Unfinished Cinema and its Postmodern Reflections,” International Journal of the Humanities 17, no. 2 (2010): 23-37.

[4]See Saige Walton, “Enfolding Surfaces, Spaces and Materials: Claire Denis’ Neo-Baroque Textures of Sensation,” Screening the Past 42 (2013), Web, www.screeningthepast.com/2013/10/enfolding-surfaces-spaces-and-materials-claire-denis’-neo-baroque-textures-of-sensation/, 24 November 2017;

“Affective Forces and Folds of Night: Les Salauds/Bastards (2013) as Baroque Dark Matter,” The Cine-Files 10 (Spring 2016): 1-25; and Cinema’s Baroque Flesh: Film, Phenomenology and the Art of Entanglement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

[5]Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 276.

[6]Brian Massumi, “The Autonomy of Affect,” in Deleuze: A Critical Reader, ed. Paul Patton (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1996), 221.

[7]See Nancy N. Chen, “‘Speaking Nearby’: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha,” Visual Anthropology Review 8, no.1 (Spring 1992): 83-91.

[8]Nigel Thrift, Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect (London and New York: Routledge, 2007).

[9]Phillip Vannini, “Non-Representational Research Methodologies: An Introduction,” in Non-Representational Research Methodologies: Re-envisioning Research, ed. Phillip Vannini (New York: Routledge, 2015), 5.

[10]See, for example, François Laruelle, Principles of Non-Philosophy, trans. Nicola Rubczak and Anthony Paul Smith (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013) and William Brown, “Non-Cinema: Digital, Ethics, Multitude,” Film-Philosophy 20, no. 1 (Feb. 2016): 104-30. As Brown notes, one of the characteristics of non-cinema is an imposition of darkness.

[11]Gregory J. Seigworth, “Capaciousness,” Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry 1, no. 1 (2017), ii, iii, Web, doi:10.22387/CAP2017.7.

[12]Simon O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art Beyond Representation,” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 6, no. 3 (December 2001), 125.

[13]1 Corinthians 13:12.

[14]See, for example, such images as “Kiarostami at Work,” Photos 12/Alamy, in David Denby, “End Games: The Films of the Iranian Director Abbas Kiarostami,” The New Yorker 87, no. 4 (14 March 2011), 65; and “The Director Abbas Kiarostami,” by Laurent Thurin Nalset, in Nicolas Rapold, “Master of Illusions Faces His Own Mirage,” New York Times 8 February 2013: AR12.

[15]Abbas Kiarostami, Fanfare 6 April 1998, Web, 24 May 2017. Other directors who have also regularly worn dark glasses in public appearances, if not for medical reasons, then possibly as an affectation or a prop, are Jean-Pierre Melville, Jean-Luc Godard, Wong Kar-wai, Tim Burton, and Claire Denis. In Agnès Varda’s recent film, Faces Places (France: Ciné Tamaris, 2017), dark glasses become one of the cross-cutting themes. Varda’s partner in this film, a young visual artist named JR, is constantly wearing dark glasses, which reminds her of Jean-Luc Godard. Varda remarks in the film that JR’s dark glasses are like “the black screen” between them.

[16]Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, trans. Tom Conley (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 31.

[17]See Chris Lippard, “Disappearing into the Distance and Getting Closer All the Time: Vision, Position, and Thought in Kiarostami’s The Wind Will Carry Us,” Journal of Film and Video 61, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 31-40; Michael Price, “Imagining Life: The Ending of Taste of Cherry,” Senses of Cinema 17 (November 2001), Web; Hamish Ford, “Driving into the Void: Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry,” Journal of Humanistics and Social Sciences 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-27; Mathew Abbott, “The Appearance of Appearance: Absolute Truth in Abbas Kiarostami’s ABC Africa,” Senses of Cinema 67 (July 2013), Web; Justin Remes, “The Sleeping Spectator: Nonhuman Aesthetics in Abbas Kiarostami’s Five: Dedicated to Ozu,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 231-42; and Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami (London: SAQI Books/Iran Heritage Foundation, 2005), among others.

[18]A reference to Chris Marker’s film, Sans Soleil (Sunless) (France, Argos Films, 1983).

[19]Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 42; 40.

[20]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 18.

[21]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 32.

[22]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 40.

[23]Henry Corbin, The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy, trans. Joseph Rowe (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1998), 156.

[24]Deleuze, The Fold, 10.

[25]Marcus A. Doel, “Representation and Difference,” in Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography, ed. Ben Anderson and Paul Harrison (London: Ashgate, 2010), 128.

[26]Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 201.

[27]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 19-20.

[28]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 18. Also a reference to Kiarostami’s film Life, and Nothing More… (Iran, Kanoon, 1992), sometimes also translated as And Life Goes On.

[29]Kiarostami, “An Unfinished Cinema.”

[30]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 282.

[31]O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect,” 127.

[32]This type of “blackout cut” was often practiced in classical cinema, when objects or characters momentarily blocked the camera. In film literature, blackout cuts have variously been described as hidden cuts, masked cuts, or invisible edits, as they are presumed to pass unnoticed.

[33]Forough Farrokhzad, “Gift” (Hediyeh), Web, www.forughfarrokhzad.org/selectedworks/selectedworks1.php#Gift, 31 May 2017.

[34]The Wind Will Carry Us, directed by Abbas Kiarostami (France, MK2 Productions, 1999), Film.

[35]Forough Farrokhzad, “The Wind Will Take Us,” Web, www.forughfarrokhzad.org/selectedworks/selectedworks1.php#The%20Wind, 31 May 2017.

[36]Hamid Dabashi, Close-Up: Iranian Cinema Past, Present, and Future (New York: Verso, 2001), 253.

[37]Dabashi, Close-Up, 253, 254.

[38]Dabashi, Close-Up, 253. She does remain silent when asked her name by Behzad, but we know that her mother has called her Zeynab.

[39]Copjec, “The Object-Gaze: Shame, Hejab, Cinema,” Gramma: Journal of Theory and Criticism 14 (2007), 176.

[40]Copjec, “The Object-Gaze,” 177.

[41]Copjec, “The Object-Gaze,” 179.

[42]Copjec, “The Object-Gaze,” 164.

[43]Hamid Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshan Banietemad’s Films,” Social Research 67, no. 2, Iran: Since the Revolution (Summer 2000), 565.

[44]Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema,” 572.

[45]O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect,” 127. He references Chapter 6 of A Thousand Plateaus, on “The Body Without Organs.”

[46]O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect,” 128.

[47]Rosi Braidotti, “The Ethics of Becoming Imperceptible,” in Deleuze and Philosophy, ed. Constantin Boundas (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 157.

[48]Khatereh Sheibani, “Kiarostami and the Aesthetics of Modern Persian Poetry,” Iranian Studies 39, no. 4 (December 2006): 524.

[49]For example, Behzad is perplexed as to why the whitewashed village is called Black Valley, not White Valley, a (for him) confusing reorganization of binaries.

[50]Sheibani, “Kiarostami,” 524.

[51]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 299.

[52]The Passion of Joan of Arc, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (France, Société Générale des Films, 1928), Film.

[53]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 286.

[54]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 287.

[55]See Yulia Ustinova, Caves and the Ancient Greek Mind: Descending Underground in the Search for the Ultimate Truth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 2.

[56]Ustinova, Caves and the Ancient Greek Mind, 1.

[57]O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect,” 127.

[58]Deleuze, Cinema 2, 201. Deleuze is quoting from Jean-Louis Schefer, L’homme ordinaire du cinema (Paris: Cahiers du cinema, Gallimard, 1980).

[59]Deleuze, Cinema 2, 201.

[60]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 287.

[61]Forough Farrokhzad, “The Wind Will Take Us.”

[62]Taste of Cherry, directed by Abbas Kiarostami (Iran, France, Zeitgeist Film, 1997), Film.

[63]Roger Ebert, review of Taste of Cherry, Chicago Sun-Times 27 February 1998, Web, www.rogerebert.com/reviews/taste-of-cherry-1998, 21 May 2017.

[64]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 282.

[65]Braidotti, “Ethics of Becoming Imperceptible,” 153.

[66]Un Chien Andalou, directed by Luis Buñuel (France, Les Grands Films Classiques, 1929), Film.

[67]It is of interest that Mr. Badii, just like Luis Buñuel in the razor scene of Un Chien Andalou, is smoking a cigarette.

[68]Homayoun Ershadi lights up a cigarette and hands it over to Kiarostami, an extension of the gesture from the previous scene.

[69]Gilles Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (London and New York: Verso, 1998), 26.

[70]Nagisa Oshima, “Banishing Green,” in Color: The Film Reader, ed. Angela Dalle Vacche and Brian Price (New York and London: Routledge, 2006), 119.

[71]Deleuze, The Fold, 10.

[72]Keith Uhlich, “Kiarostami at MoMA, Day 1: Birth of Light and Taste of Cherry.” Slant 6 May 2007, Web, www.slantmagazine.com/house/article/kiarostami-at-moma-day-1a-birth-of-light-taste-of-cherry, 24 November 2017. Lumière and Company includes a different short by Kiarostami, Dinner for One (Iran, France: Cinétévé, 1996).

[73]The most typical use of time-lapse is usually sunset to sunrise.

[74]Noël Burch coined this term in comparison to a “pillow-word” (makurakotoba) in Japanese poetry, “a conventional epithet or attribute for a word,” that serves a brief auxiliary function in a poem. Based on this analogy, “pillow-shots” are scenes of everyday life seemingly disconnected from the main plot, and without humans present in them. In To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1979), 160.

[75]Vannini, “Non-Representational Research Methodologies, 9.

[76]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 280.

[77]Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Spoiler Alert,” Chicago Reader 8 June 2006, Web, www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/spoiler-alert/Content?oid=922348, 22 May 2017.

[78]See Tom Paulus, “Truth in Cinema: The Riddle of Kiarostami—Part Two,” Cinea 3 January 2017, Web, https://cinea.be/truth-cinema-the-riddle-kiarostami-part-two/, 22 May 2017.

[79]Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 281.

[80]See Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 12.

[81]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 122.

[82]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 120.

[83]Deleuze, Cinema 1, 110-11. Regen (Rain), directed by Joris Ivens (Netherlands: Capi-Holland, 1929), Film.

[84]Deleuze, The Fold, 5. Deleuze is quoting from Letter to Des Billettes, December 1696 (GPh, VII, 452).

[85]“It’s a good thing we took our pills,” they say right before the power is cut off, wondering if any of the mosquitoes carry malaria.

[86]ABC Africa, directed by Abbas Kiarostami (Iran: IFAD, 2001), Film.

[87]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 42.Think also of blackouts during the Special Period in Cuba or extended periods of time without electrical supply on some Caribbean islands after the recent hurricanes Jose and Maria.

[88]Bozak, Cinematic Footprint, 43.

[89]See, for example, Vered Maimon, “Beyond Representation: Abbas Kiarostami’s and Pedro Costa’s Minor Cinema,” Third Text 26, no. 3 (May 2012), 331-44.

[90]See Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[91]See Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, “What Is a Minor Literature?”, Mississippi Review 11, no. 3 (Winter/Spring 1983), 13-33.

[92]Deleuze, Cinema 2, 217.

[93]Deleuze, Cinema 2, 273.

[94]Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What Is Philosophy?, trans. Graham Burchell and Hugh Tomlinson (London and New York: Verso, 1994), 108.

[95]Conversation with Ahmad Kiarostami at the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, about 24 Frames, 13 September, 2017. For instance, Ahmad Kiarostami talks about the zigzagging path in Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987), trampled down by a class of children who were directed to walk back and forth across the hill. Another example includes a piece of wood “spontaneously” split apart by the waves in Five, which occurred because Kiarostami hid an explosive in it (see Mahmoud Reza Sani, Men at Work: Cinematic Lessons from Abbas Kiarostami [Los Angeles, CA: Mhughes Press, 2013], 16).

[96]Peirce’s three trichotomies of the sign (Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buchler [New York: Dover, 1955]) influence Deleuze’s analyses of the image in the Cinema books.

[97]Xueili Wang, “Sleeping Through Kiarostami,” Los Angeles Review of Books 7 October 2016, Web, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/sleeping-through-kiarostami/, 24 November 2017. A few reviews of the screening of 24 Frames at the Cannes Film Festival described sleeping spectators in the audience: “During the screening at the Lumière, where I sat in the balcony, probably half the audience in my area got up and left in the first hour. Over half of those who remained spent portions of the film asleep,” Nolan Kelly, “24 Frames: The Last Word of Filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami,” The Pavlovich Today 12 August 2017, Web, http://thepavlovictoday.com/mixed-media/24-frames-last-word-filmmaker-abbas-kiarostami/, 24 November 2017. For a scholarly treatment of “the sleeping spectator,” see Remes, “The Sleeping Spectator: Nonhuman Aesthetics in Abbas Kiarostami’s Five.”

[98]Deleuze, in “The Greatest Irish Film (Beckett’s “Film”), gave this assessment of Beckett, in Essays Critical and Clinical, 26.